A labour of love in Kashmir

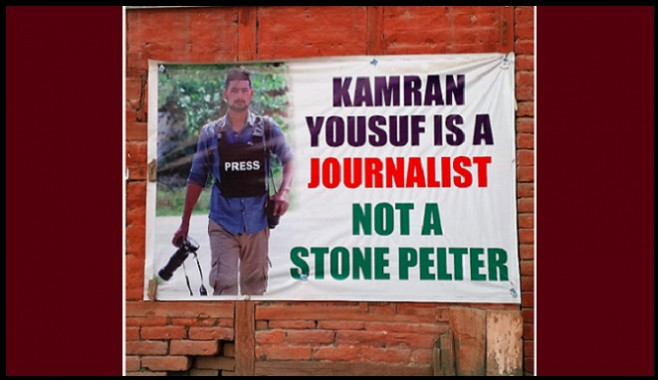

Poster on wall in Srinagar in solidarity with Kamran Yousuf, detained by the NIA (Photo: Laxmi Murthy)

Srinagar: For journalists in Kashmir, getting the complete story and a quote from all sides is “virtually impossible” and it becomes particularly severe during an Internet and mobile phone shutdown, according to a report released by the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ).

The report, “Kashmir’s Media In Peril: A Situation Report”, said there is “no system in place to get official versions of incidents from police or security agencies”. It quoted senior journalist Yusuf Jameel saying, “While there is no direct censorship, circumstances are created to make it difficult to work. There is no system in place to talk to the responsible person in the police or security agencies to get the official version.”

The report went on: “News-gathering and verification are fraught with challenges in Kashmir. From obstacles to physical access to villages on the contentious Line of Control (LoC) with Pakistan to routine denial of information from official sources, getting the complete story and a quote from all sides is virtually impossible,” the IFJ said.

Citing a case of a “suspected militant” killed in Uri village in northern Kashmir, it quoted villagers having said, “the slain was a civilian - a grazer” and said: “But it was impossible to verify because journalists were denied access and officials refused to comment.”

The report is based on the author Laxmi Murthy’s meetings with reporters, press photographers, editors and media owners last month in Kashmir Valley. It has documented the key issues faced by the media, including the challenges of living and reporting in a conflict zone, precarious working conditions, physical safety, government control through regulating advertisement revenue, lack of unity among journalists, the problems of photojournalists at the frontline, access to information that is controlled by government and security forces, and regulation which has shut down newspapers (the Kashmir Reader).

Apart from these issues, the report highlighted the drowning of photojournalist Shafat Siddiqui in the 2014 floods, the blinding of Mir Javed and Zuhaib Maqbool by pellets in 2016, the arbitrary ban on the Kashmir Reader for three months in October 2016, and the arrest of Kamran Yousuf by the National Investigation Agency in September 2017. It termed women journalists and reporters living and working in remote areas as even “more vulnerable”.

Given that the Internet is “routinely shut or slowed down on Fridays”, the report said these shutdowns and censorship have restricted the information flow and the rights of journalists to report.

Highlighting the methods adopted by the army in restricting information, it said: ‘They intimidate villagers to the extent that common people are afraid to talk to journalists due to fear of repercussions”.

Free movement is hobbled

According to the IFJ, the movement of journalists in the Valley is severely curbed during curfews imposed by the government and the "discrimination against local journalists is open, with names like Butt or Geelani…not issued passes”.

“Often, what amount to curfews in practice are termed ‘restrictions’ and passes are deemed unnecessary, but on the ground, the mobility of journalists is severely curtailed,” it said.

Reporter Hakeem Irfan told the IFJ that the military had restricted movement and residents were not allowed to come out of their houses, even if they were journalists.

“Yet, the well-known Delhi-based journalist Barkha Dutt with NDTV did her piece-to-camera from a military vehicle right outside his house! Irfan said that on a news-gathering trip to Gurez on the border, the Grenadiers demanded that he sign a document saying that he was agreeing not to report. He refused to sign,” it said.

‘He doesn’t work for us’

Noting that 21 journalists were killed in the last three decades, it said that although the “targeted” killings have stopped yet, the vulnerability of the media continues. Lack of support from news organisations seems to increase the vulnerability of journalists. One example is photojournalist Kamran Yousuf who is being investigated by the National Investigation Agency and is currently languishing in Tihar Jail in Delhi, “with no charges framed against him”.

“The 20-year-old from Pulwama had been contributing to Greater Kashmir, Kashmir Uzma and other publications, but has been disowned by them. A news item about an earlier assault where he was identified as a “GK lensman” was taken down from the Greater Kashmir website after his arrest by the NIA,” the report said.

One journalist told the IFJ how, after recently being beaten by the Special Task Force of the J&K police and hospitalised for two months, he had no support from his employer. “Far from any support from my organisation, my editor did not even phone me”,” the report quoted him as saying.

According to the IFJ, reporters in the districts receive more threats than those based in Srinagar.

“Regular visits by army personnel and intelligence officers to the homes of journalists and harassment of their families, has become routine enough to be unremarkable - the annoyance and surveillance being borne as a fallout of working and living in a conflict zone.

“Journalists report being picked up and taken to Military Intelligence (MI) camps and interrogated, sometimes being detained with no charges. Questions about their stories sometimes lead to self-censorship to minimise harassment to families who live in fear.”

Fearless reporting, despite the perils

The report lauded Kashmir’s newspapers for taking on the challenging task of reporting the militancy and its impact on the people and highlighting the “might of the Indian state and human rights violations committed by the security forces and also by the armed militants”.

It said: “The media in Kashmir held its own despite pressures from the government, military and the militants.”

Highlighting the dangers journalists have to negotiate, it said that the Public Safety Act (called ‘a lawless law’ by Amnesty International) which allows for the detention of a person without trail for up to six months, is applicable to journalists.

The report found that no television channel, except for cable TV and national channels, broadcast in the state and the cable operators, on government orders, blocked them on several occasions.

Using advertising as a lever

Local business has been hit by the insurgency and corporates from outside the state are loath to spend advertising revenue here, said the IFJ. Some companies, such as Airtel, have been issued directives by the government not to advertise in Jammu & Kashmir.

This has forced newspapers to sustain themselves on government revenue in the form of advertisements and paid public notices. The advertisements, which are hardly a favour to the newspapers because they carry the bulk of the government’s press releases in any case, are “disbursed according to discretion and favour”.

“Pro-government publications are favoured with government houses, land, and other ‘privileges’ for propagating the official line. Those who do not play the game, pay a price,” it said.

Haroon Rashid, editor of Urdu language daily Nida-e-Mashriq, told the IFJ: “Even when reporting facts, we are labelled as ‘anti-national’.”

Without naming the daily Kashmir Reader, he cited the government’s advertisement blockade after the paper published slain militant leader Burhan Wani’s photo on his death anniversary on 8 July 2017 on the grounds that it was “promoting militancy”.

“If people are attending the funeral of slain militants in large numbers, this is a fact. How can it be considered as glorifying militancy?” asked Rashid. He recounted what the Director, Information, told editors during a meeting. “If you take government advertisements, we also expect something.”

Low standards and working conditions

Pointing to the Rs 32-crore advertisement revenue distributed by the state government last year, the IFJ said that “some journalists felt that the government could exercise control not by censorship of content, but by making minimum standards, salaries and benefits mandatory and deny advertisement revenue to publications that did not comply”.

It added: “The lack of investment in professional journalism is displayed in the poor salaries paid to field reporters, and minimising expenditure by relying on newspaper vendors and hawkers in the districts to phone in with local updates which are then subbed and packaged as “news” – thus completely bypassing professional journalists.”

One reason for the low wages, pointed out by journalist Peerzada Arshad, who works with Xinhua, is civil servants moonlighting as journalists in the evening. “They package agency news in the manner required by the publication, for very little payment,” he told the IFJ.

Calling journalism a “labour of love”, the IFJ said that, as a profession, it has not yet become institutionalised and the “structures of recruitment, wages, promotions and benefits are not uniform in any media house”.

“There is only one relatively large media house, Greater Kashmir, which is relatively more structured in terms of recruitment, salaries and promotions.”

Masood Hussain, editor of Kashmir Life and member of the newly formed Kashmir Editors’ Guild, told the IFJ that he feels that there is no question of a structure like a Wage Board to regulate salaries. “We need to see the reality. But we are talking about health insurance at the very least,” he said.

The report mentions the low wages, saying that journalists work for as little as Rs 5000 per month.

“Interns often carry out major tasks at the paper, sometimes with no salary for up to six months. In such a scenario, there are no appointment letters, no medical benefits, insurance or pensions or provident fund. Written contracts are not drawn up and jobs and work assignments go according to oral agreements which are not binding,” the report said.

“Reporters who travel for stories usually end up paying for conveyance themselves, unless they are lucky enough to hitch a ride with their colleagues from the national or international media on their bikes or vehicles. Photojournalists buy their own equipment, having to bear the costs of repairs and upgrades themselves. Phone bills are also borne by reporters,” the report found.

In addition, the industry is saturated, with newly established journalism schools in Baramulla and Anantnag producing 120 graduates every year. The glut of new entrants working for very low wages in order to gain experience and bylines, devalues the profession.

According to the IFJ, online abuse and intimidation are growing in the region and cites the case of Asif Qureshi of ABP TV channel who had to deactivate his Facebook account after receiving a “barrage of abuse within minutes of posting any story.”

Once, an extremist leader threatened to broadcast a call to burn Qureshi’s house from the local mosque. He feels the discourse has changed from the 1990s when the people of Kashmir felt that the media was telling their story.

Quoting Qureshi, the report said: “Today, he says, there is a lack of faith and even animosity between the public and journalists, some of whom are dubbed ‘agents’.”

Moazum Mohammad is a journalist based in Srinagar. He works with Kashmir Reader.