A reporter’s chilling hindsight

Reporters in this country should write more books. They nail the system quite devastatingly when they piece together their notes after the story has run its course. Sometimes long after. Does publication, often after several years, herald the prospect of retrospective justice? Unlikely. For that you need to be a society with a keen sense of fair play which we manifestly are not. When it comes to ourselves. Shashi Tharoor may be fleetingly lionized when he makes a debater’s case for reparation by Britain for its colonizing of India. But injustice at home, even spectacular injustice, is taken in stride.

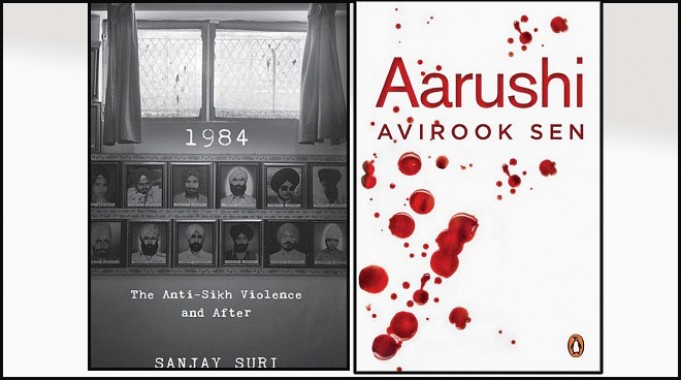

This is about two books which hit the bookstores in July. One going back to what happened three decades ago, the other dealing with events still fresh in memory. Each is stunning for what it reveals, each is an indictment in its own way of this country’s police and investigation system. The scale of the miscarriage of justice is not comparable . But what the two books tell us about the system that makes it possible, is. In one case under pressure from the ruling class, and in the other instance under a pressure which is difficult to fathom.

1984, by Sanjay Suri, published by Harper Collins

There is a section of India’s intellectual class which is far more willing to forgive and forget 1984 than 2002. They should read this book for its eyewitness documentation of the role of Congressmen and the police, in that order, in perpetrating a pogrom after Indira Gandhi was assassinated. A reporter eavesdropping below a window at a Karol Bagh police station overhears a Congress MP demanding to know why his men, out looting Sikh homes, have been arrested. He hears a middling senior cop in that room tell the MP that he is protecting criminals. He hears the senior most officer in the room ticking off in front of the politician, a station house officer who tried to do his duty.

At the Rakabganj Gurdwara a CRPF platoon stands by and watches as a screaming crowd advances upon the gurudwara. Then the crowd holds back at a slight gesture from Congressman Kamal Nath. Evidently he and the crowd had a connection. At the same scene the reporter also records the astonishing sight of a senior police officer doing an agile sideways sprint to move out of the way of the menacing, advancing crowd. A gentleman related to the Gandhi family.

Three thousand killings took place in three days during which the police failed deliberately--according to a police enquiry conduced later--to protect a besieged community. That enquiry report was stopped in its tracks. Ved Marwah, the Additional Commissioner of Police inquiring into police failures a few months after the riots, remembers finding that the central control room recorded distress calls coming in every few minutes, but there was no movement of police. The most affected police stations recorded no movement of police at all. They just stayed put. Did they do that of their own volition?

Meanwhile groups of rowdies were mobilised to ransack shops, to ring Sikh men with burning tyres. The tyres had been soaked with kerosene. These saw the emergence of the kerosene tyre as weapon, wielded by men who were confident that there was no need for them to hide their weapon. If you were a victim in Trilokpuri for instance, you could not go the local police station because it was backing the killers.

The public broadcaster Doordarshan had allowed scenes of men shouting khoon ka badla khoon se lenge (blood for blood)to go on air. If the government actually wanted to establish culpability for the killings, it would have been easy enough, surely, for the police to examine the footage to identify the persons who were shouting?

Meanwhile as the city burned, the police commissioner decided to station himself at Teen Murti Bhavan where Mrs Gandhi’s body lay in state.

There is more here, including an oblique admission of the culpability of the Congressman in Karol Bagh by Rajiv Gandhi, as the reporter corners him in Amethi, while covering the elections which followed.

Writer’s disclaimer: Sanjay Suri was a colleague at the Indian Express at the time of the 1984 riots.

Aarushi, by Avirook Sen, published by Penguin books.

This book is a must read. It is by a reporter who begins covering the trial in the Aarushi Talwar murder case in 2012, tracking its bizarre twists and turns and interviewing many players, including investigators, lawyers, witnesses. He documents many tiny bits of evidence that surfaced or failed to, quotes from testimonies given by witnesses on both sides, and documents statements that changed.

As the trial progresses and the initial investigation comes under the scanner, he describes the circumstances of the latter. The night after the May 2008 murders the police arrive an hour after they are called, and very soon the crime scene has everybody tramping around including the media. They intend to find a locksmith the day they discover the first murder but end up not doing so, and therefore not investigating the terrace till the following day.

The police also stand by and watch after the Talwars leave to cremate their daughters body, and a few women who are in the flat at that point decide to get it cleaned and swept, unwittingly wiping away crucial evidence.

In the days that follow the police trawl the dead teenager’s social media accounts and spill out what they find to the media. An Uttar Pradesh inspector general of police who does a briefing, gets the victim’s name repeatedly wrong. His early creative solving of the case is later found to be derived entirely from another suspect’s statement. The one against whom the most incriminating evidence was eventually found.

A variety of players figure in this book. There is a post mortem doctor who makes six changes to his original report over three years. Apart from not marking slides of vaginal swabs, which were later swapped. Changes are made to the post mortem findings by the CBI after interviewing two sweepers who were in the room when it was originally being conducted, more than a year earlier. They testify to vaginal dilation!

There is a forensic scientist who changed his original statement about where an incriminating blood stained pillow cover was seized from. Another who is brought aboard the investigation by the CBI to do a crime scene analysis more than year after the murder. Sen descfibes how he sets about delivering on this assignment.

He documents how the forensic findings on which blunt instrument was used to cause the head injury to Aarushi Talwar changed over time from a khukri to a golf club. The weapon does not lead the to the possible culprit, a prior conclusion on who the culprit is leads them to look for an appropriate weapon which fits the theory.

He details the narco analysis of various suspects, what they showed, and the weight the investigators, prosecutors, magistrate and judges decide to attach to each one.

He describes a key witness produced by the CBI declaring solemnly as she begins her testimony: Jo mujhe samjhaya gaya hain, wahi bayan mai yahan de rahi hoon. (Whatever was taught/explained to me I am testifying here.) To the consternation of the investigating agency, which then whisks her away from the court.

The reporter also finds it necessary to explain how the Ghaziabad courts function compared to those in Delhi, and why a criminal lawyer used to these courts can bring more value to his client that the better names hired from elsewhere in the country. There are also clear-eyed insights here into the pluses and minuses of having top lawyers handle your case pro bono.

And then there are revelations of evidence swapping which can make your blood run cold.

If a body of media lived off this case for months, helping to perpetrate injustices done, it is fitting that someone from the media has now taken it upon himself to document painstakingly how little it can take to queer the pitch in the Indian justice system. In the process, he does its victims a service.