Aadhar: why classification matters in law making

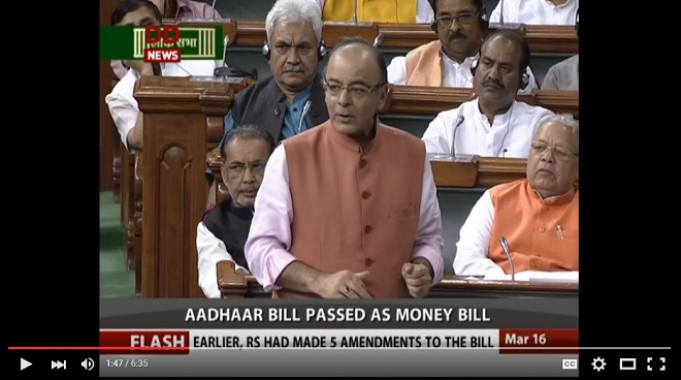

Arun Jaitley speaking in Lok Sabha on March 16, 2016

When the Aadhar Bill was introduced by Finance Minister, Arun Jaitley, as a money bill in the Lok Sabha last month, it caused an uproar because it was classified as a money bill on the grounds of enabling better financial targeting. Critics however focused on its collection of citizen-related data. This piece is about how classification has historically proved a potent tool in the hands of lawmakers (either legislative, or executive policy, or judicial pronouncements) to negotiate the legitimacy of new technologies.

The Bill, titled, The Aadhaar (Target Delivery of Financial and Other Subsidies, Benefits and Services) Bill, 2016 was a revised version of the earlier National Identification Authority of India Bill 2010, but nevertheless, like the earlier Bill, dealt with the collection of citizen-related data (including biometric information) and the establishment of an authority to govern this process under the Unique Identification (UID) project or what is popularly known as the Aadhar scheme.

The fascinating feature about this new Bill however, is that unlike the 2010 Bill, it was introduced as a money bill in the Lok Sabha. This implied less involvement of the Rajya Sabha (where the current government is also short of a majority) in framing the Act- The Rajya Sabha can only make recommendations but no amendments to a money bill and must return it to Lok Sabha within 14 days, or else it is considered approved. And it was in this way that the 2016 Bill was finally formalized into an Act, which has the force of law.

Arun Jaitley justified this money bill classification by pointing out that the 2016 Bill was significantly different from the 2010 Bill and that it satisfied the requirements of a money bill as laid down under Article 110 of the Constitution. The justification provided was that since the Bill will facilitate targeted distribution of government subsidies to the relevant population in the country, it does fall under the category of a money bill.

However, many have been appalled by this classification of the Aadhar Bill 2016 as a money bill- finding it a strategic (and maybe lowbrow) political move- rather than fair or rational. This, even as it is underscored that there are many problematic aspects concerning privacy and data collection in the 2016 Bill as there were in the 2010 Bill, and that the Aadhar scheme, thanks to its faulty technological architecture, is actually “a surveillance project masquerading as a development intervention because it uses biometrics”. And because of these reasons, the argument can be extrapolated to say that the 2016 Aadhar Bill should never have been passed as a money bill in our Parliament.

But why this uproar over mere classification of a Bill? What is so important about dubbing Aadhar Bill as a money bill as per our Constitution, that it has become so controversial?

Why is classification of new technologies important in lawmaking?

One obvious answer to this question, of course, is that if the Aadhar Bill had not been classified as a money bill, it would probably have never been approved by the Parliament and passed into law - considering that the Bill was heavily critiqued in the Rajya Sabha, where the Government also did not have majority. This makes the process of classification of new technologies like that of Aadhar, all the more important, because it influences the possibility of legal sanction for such technologies, which in turn, legitimises the use of such new technologies.

Take the Aadhar scheme, for example...The entire UID scheme had been a matter of much controversy for more than half a decade now. It has also been the subject of analysis for various Parliamentary Standing Committees, as well as a Supreme Court ruling (KS Puttaswamy v. Union of India), which expressed serious concerns over its provisions allowing for the collection and storage of biometric information. In short, the employment of biometric and data collation technologies which Aadhar allows for have been a matter of contention for some time now on grounds for data protection and privacy.

But formalisation of these provisions into the Aadhar Act adds legal sanction to these new technologies employed under Aadhar. It has augmented their legal authority which was missing before the passage of the Aadhar Act last month. And such legal authority to Aadhar technologies could only be managed upon their classification as a subject matter of a money bill. This is significant because such employment of classification strategies for the solicitation of legal sanction for new, controversial technologies is not unique or one-off. In fact, it is a well-established trend at the intersection of law and new technology.

There is a history...

Classification has historically proved a potent tool in the hands of lawmakers (either legislative, or executive policy, or judicial pronouncements) to negotiate the legitimacy of new technologies. The 2005 decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in the Brand X case is classic in this sense. At its heart, the Brand X case considered an issue of classification under the U.S. Communications Act as amended by the Telecommunications Act of 1996, concerning broadband cable internet service. In this case, the Communications Act defined among others, two categories of regulated services: telecommunication carriers, and information-service providers, and different regulations applied to each category. The case then revolved around the question of whether whether broadband internet provided via a cable modem – a new technology at the time – should be classified as a “telecommunication carrier”, or as an “information-service provider”?

While the majority opinion led by Justice Thomas held that cable modem broadband internet should be classified as an “information-service provider,” the dissenting opinion from Justice Scalia reasoned that it should be classified as a “telecommunication carrier.” The justification for such vastly different classifications for the same technology was found in comparing the new technology of cable broadband with different things (Justice Thomas compared broadband cable to a car, and Justice Scalia compared it to pizza delivery.) And such different comparisons enabled focus on vastly different aspects of the new technology in each opinion.

So while the majority opinion focused on the final purpose or function for which cable broadband is used by the citizen (eg. for communication), the dissent emphasized upon the manner or means in which the broadband service is delivered to the consumer (eg. as a whole package of content and delivery mechanism and not discrete units). Ultimately, choosing one classification over the other for the novel technology led to a very different set of legal regulations governing it, than would have been the case if it were classified differently.

The politics of classification in Indian law

In India, a similar battle over legal classification was implicitly raged when our courts were forced to face the issues presented by new communication technologies like social media, on the internet in the 2015 judgment of Shreya Singhal v. Union of India. Briefly, the case was brought before the Supreme Court of India to challenge, among other provisions, the constitutionality of Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, 2000, which criminalised a variety of online speech on broad grounds, including “information which is grossly offensive”, and “electronic mail message for the purpose of causing annoyance or inconvenience.”

The constitutionality of this section was successfully challenged on the grounds of violation of the freedom of speech and expression and arbitrariness. But the implicit question asked in arriving to this conclusion was again, a question of classification. And that question was: Can “grossly offensive” and “annoyance or inconvenience” causing information which is generated through new online communication technologies, be classified as criminal? Or is the non-criminal category more appropriate for sharing of such kind of information? And as is well-known, the Court laudably chose the second classification option, leading to a whole different kind of governance regime for online communication technologies in India than what would have been the scenario if the Court had chosen the classification category of criminal.

Even before this, in the case of K.A. Abbas v. Union of India in 1970, when the interaction of law with film technology was still fairly new in India, a question of classification has arisen. The immediate issue debated in the case was whether the pre-censorship of films was constitutional? The pre-censorship of an older media form, viz., books, was not considered constitutional. Hence, the classification question which was then asked was whether films fall in the same category as books, or do they constitute a different category altogether? Drawing comparisons between films and books and focusing on certain functional, affective aspects of each, the Court finally reasoned that films could not be classified in the same category as books. And because of this, they could be legally governed differently from books – even while books could not be pre-censored, films could.

Coming full circle to the money billing of Aadhar…

The point I am trying to make in all this is that the tactical use of seemingly problematic classification, especially when governing new technologies, is nothing new in lawmaking. It has been employed in a number of lawmaking situations, like Jaitley rightly points out, as a means to reach both desirable and undesirable ends from a citizen’s point of view. Considered in this light, the categorization of the Aadhar Bill 2016 as a money bill falls in an established tradition of strategic lawmaking. This is, of course, not to say that such a tradition cannot be challenged, but rather to illustrate that as a legal tool, strategic classification has skillfully served both the idea of individual freedom (as in the Shreya Singhal case), as well as the machinery of Statist repression (as in the KA Abbas case).

The problem with how the Aadhar Act was legislated then lies not so much in the “wrong” choice of its classification as money bill, but rather in the way we allow the idea of classification itself to dominate our legal processes. How can we then redesign the tool of legal classification in a way that it intrinsically serves citizen interests rather than merely pandering to political games?

Even as the Aadhar Act comes into force in a law-abiding world where citizen privacy and personal liberty are becoming increasingly compromised, it is certainly a more productive question to ask. Especially if we are seeking to create sustainable institutional change in our legal regimes over mere firefighting whenever inevitable accidents like the Aadhar Act happen. What makes it both inevitable and an accident are long-standing structural problems involving the concept of legal classification, so maybe it is time to reexamine the role of classification in our lawmaking.

Smarika Kumar is an independent legal researcher and was formerly with the Alternative Law Forum, Bangalore.