Arrested, tortured, jailed in South Bastar

Picked up in July and September end, two Hindi language journalists from the Darbha block in southern Bastar have been under arrest, charged with supporting Maoist rebels, and subjected to custodial torture. The lack of clarity around their alleged offences and the lack of clear evidence, highlight the perils of being a rural reporter in the militarized and polarized resource-rich region of South Chhattisgarh where the state and Maoists have been locked in a decade-long battle.

Santosh Yadav, who used to gather news for multiple Hindi newspapers including Dainik Navbharat and Dainik Chhattisgarh, was arrested by the police on September 29th. His name was subsequently added to a case where 18 villagers are in prison, charged with an encounter on 21st August during a road-opening operation by the security forces in which a Special Police Officer was killed.

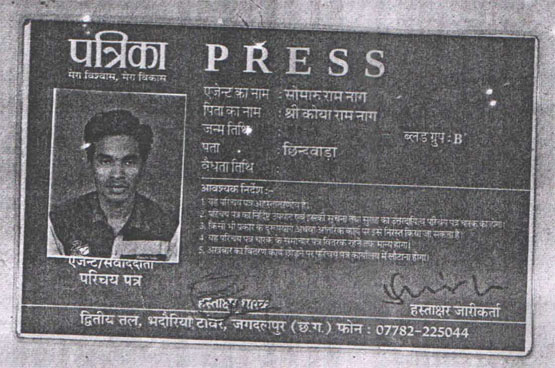

Somaru Nag's Rajasthan Patrika press card

Somaru Nag, an Adivasi journalist who was a stringer-cum-news agent with the Rajasthan Patrika was arrested on July 16th. He has been charged with keeping a look out on the movements of the police while a group burnt a crusher plant employed in road construction in Chote Kadma on 26th June.

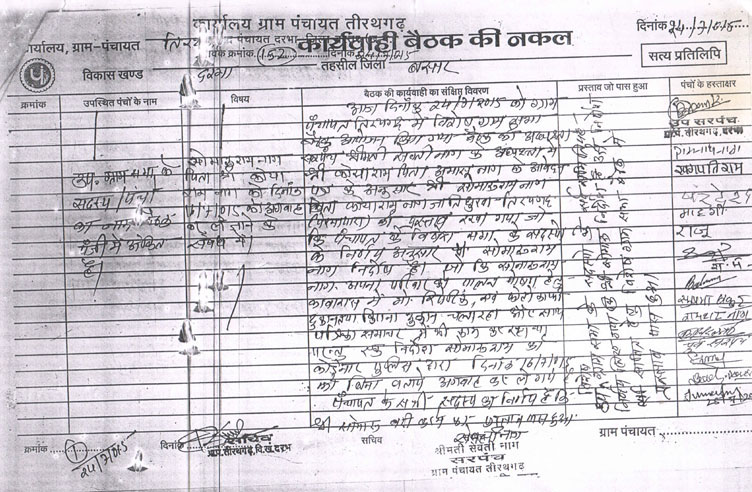

Nag’s younger brother, Sonaru, said Nag had been picked up from their mobile phone shop on the outskirts of Darbha town by policemen in plainclothes on the 16th of July, and was shown as being arrested on the 19th of July at the Parpa police station. Sonaru said the family subsequently met Nag in prison. “We saw that he had been beaten up very badly. He told us, ‘please speak to the other journalists and ask them to help me get released.’

“When he has committed no crime, how can he admit to the crime the police are pressurising him to...”, their letter of 25th July said. Sonaru says the family has no clue why the police arrested Nag: “Someone pointed to him, and that was enough for them to pick him up. They also took away his bike.”

Tirathgarh gram sabha resolution for Somaru Nag, July 26, 2015

Yadav had been harassed and tortured by the police for over a year, before his arrest last week - a fact highlighted by the August 2015 bulletin of the PUCL (People’s Union for Civil Liberties) though it does not name him. On 25th May 2013, Yadav, a Darbha resident, was one of the first reporters to reach the section of the valley where armed Maoist rebels assassinated and injured over 50 people, from Congress politicians to migrant Adivasi labourers.

According to Kamal Shukla, a journalist based in Kanker district of North Bastar, Yadav’s speedy presence on the scene following the killings was reason enough for the police to believe that he was tied to the Maoists. “Your editor says rush to the spot, and a stringer has to do that. Just doing our job makes us suspect in the eyes of the police and the Maoists,” said Shukla.

According to reporters in the region, from June this year, the police pressure on Yadav grew. Harjit Singh Pappu, the Jagdalpur-based Bureau Chief of the Dainik Chhattisgarh, a paper for which Yadav used to gather news and take photographs, said “The last time I met Santosh was two to three months ago. He told me that the police had kept him in custody, stripped him, and threatened to beat him.”

According to the PUCL bulletin, and a 4th October representation to the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) by the Human Rights Defender Alert organisation, Yadav was under great pressure from the police to become an informer.

Bastar’s Superintendent of Police Ajay Yadav denied allegations of torture and police pressure on Yadav and asserted that the arrest was a legitimate one: “We had been continuously watching his movements. He was very active in that area, and had links with the local (Maoist) commanders. He used to supply material to them.” The SP said he had no information on Nag’s arrest.

Both reporters have had little support from the publications that used their work. Sonaru says they met the Patrika editor in Jagdalpur who told them that, since Nag was already under arrest, there was nothing he could do. In a front page written piece, Sunil Kumar, the Raipur-based editor of the Dainik Chhattisgarh, said Yadav used to work for them in the past, and since the matter was in the court, due process demanded that the police get an opportunity to prove their allegations, but also demanded that the state government disclose the basis of Yadav’s arrest. He acknowledged that reporting in the villages of Bastar was rife with danger: “Police na-khush toh giraftaari, aur Naxal na-khush toh maut (Upset the police, and face arrest. Upset the Naxals, and face death.)”

Nag and Yadav are being currently represented by an all-woman legal aid team called Jag-LAG, which is based in Jagdalpur. Nag has been charged under the Indian Penal Code and the Arms Act; Yadav under the Indian Penal Code, the Arms Act, the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, and the Chhattisgarh Public Security Act (CPSA). Their lawyer, Isha Khandelwal added, “When the police presented Yadav in court on October 1, they claimed that he had confessed to being allied to the Maoists. Along with the other villagers, he has been booked under acts, which make getting bail very difficult. It is likely to be a long haul.”

Enacted by the Chhattisgarh state government in 2005, ostensibly to aid the fight against the Maoists, the CPSA designates a range of activities as ‘unlawful’, including representations by an individual or an organization "...which interferes or tends to interfere with the maintenance of public order.” Worryingly for journalists and rights defenders in the state, all offences registered under this act are non-bailable, and sweeping powers and discretion are given to the district officials, while framing charges.

“I fear for Yadav’s life. Even if he is released, there is a great likelihood that he will be targeted by the Maoists,” said Shukla, recalling prior assassinations by Maoists of two journalists in the region - Sai Reddy (also booked by the police in 2008 under the CPSA), and Nemichand Jain. The Maoists justified both killings saying the journalists were police informers, though they subsequently apologised for Jain’s death, in the face of a media boycott. In prior communications to journalists, the rebels have argued that the concept of neutrality does not hold in a class war.

Such extreme views mirror that of the state security forces. Pappu said, “You have to go to villages, go to the jungles, meet people. You have to report the other side also. But the police thinks that if you are meeting them (the Maoists), you must be a part of them.” Simultaneously, the police do not hesitate to deploy local journalists to reach out to Maoists when they feel the need, such as to carry out negotiations for the release of kidnapped officials.

In this dangerous reporting landscape, rural stringers are especially vulnerable by virtue of having little social capital, and living and working on the frontlines. Sudha Bharadwaj, a Bilaspur-based human rights lawyer and PUCL member pointed out, “They don’t get the immunity, protection or working conditions that journalists in the national media get (even though no outside journalist can really report in these areas without a local journalist’s assistance for travel, and interpretation of the local Adivasi language).”

Nag was a rare Adivasi journalist in the region. Yadav was a very active reporter, and villagers often approached him for help since he knew Gondi and Hindi, according to Khandelwal. “Many villagers came to us for legal aid, via him,” she said. Nag and Yadav’s are among a string of arrests of villagers made in the Darbha area by the police in past weeks, she added.

Bastar’s journalists are planning a meeting on October 10 in the state capital of Raipur. Shukla and Pappu said the aim of the meeting was to demand recognition by media organisations and state and security officials of journalists working in the conflict zone, to devise a strategy for greater safety and protection against arbitrary police action, and to protest the incarceration of their colleagues.

“Over the years, the situation in Bastar has become such that if you want to be a journalist”, said Shukla, “the expectation is that you be dishonest with yourself, close your eyes, and pretend that you can’t see anything.”

Chitrangada Choudhury is a Orissa-based multimedia journalist and researcher, and a Fellow with the Open Society Institute (suarukh@gmail.com).