Awful reasoning and tortuous verbosity

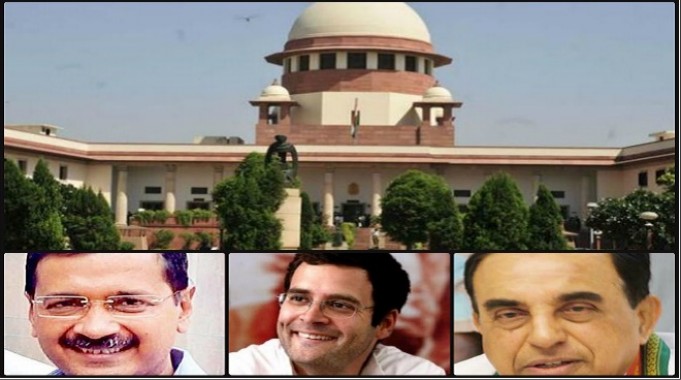

On May 13, the Supreme Court delivered a judgment upholding the constitutionality of criminal defamation provisions. This judgment in the case of Subramaniam Swamy & Others v. Union of India was a rather high profile case since Swamy’s fellow litigants were Rahul Gandhi, Arvind Kejriwal and others. To be sure, this constitutional challenge to Section 499 was always a difficult case and it should not surprise anybody that the constitutionality of the provision was upheld.

What should, however, concern every Indian, is the awful reasoning and tortuous verbosity running through the breadth of the 268 page judgment by Justice Dipak Misra. The literary violence of the judgment has been neatly unpacked by Tunku Varadarajan in this piece titled ‘Judgment by Thesaurus’, published on the Wire and is recommended reading for those of you who are planning to read the judgment, which can be accessed over here. Moving on to an analysis of the judgment, let me begin by introducing the constitutional challenge.

The constitutional challenge: unreasonable restriction?

Defamation in India can be divided into two categories: civil defamation and criminal defamation. The remedies for civil defamation include an injunction against publication of the defamatory speech and damages for the injury suffered by the person so defamed. On the other hand, a guilty verdict for criminal defamation is punishable with a prison term of two years and/or a fine.

The essence of the constitutional challenge was whether the law imposed an unreasonable restriction on the fundamental right to free speech enshrined in the Constitution. The right to free speech is, however, not an absolute right and is subject to reasonable restrictions which allow the state to enact law in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, in relation to defamation etc. The petitioners in this case argued that in order to be reasonable, a restriction on free speech is required to be proportional to the object and effect of the restriction.

In the case of Section 499, the restriction imposed by the law is criminal imprisonment and the object of the restriction is to safeguard the reputation of a person. According to the petitioners, the effects of the restriction on the fundamental right to free speech i.e. the threat of imprisonment, has a “chilling effect” on future free speech.

It was argued that journalists and citizens are so worried about the possibility of prosecution that they would rather not write or say anything which may be construed to harm the reputation of a person, company or government officer because of the possibility of being jailed for two years, even if there is substantial basis for what they want to say.

While a Subramaniam Swamy may be irrepressible and continue to shoot off his mouth regardless of what law is on the books, most journalists and editors, I guess, would rather keep silent than provoke criminal defamation proceedings which can result in the loss of liberty. Thus, the argument goes, Section 499 is having a “chilling effect” on free speech and is eviscerating the very liberty that is to be protected by the Constitution, thereby making Section 499 a disproportionate measure, especially in the context of its objective to protect reputations. Therefore, given the “chilling effect”, the petitioners argued that the provision be classified as an unreasonable restriction on the right to free speech.

There were also some arguments on the legality of Parliament making defamation a criminal offence rather than a civil offence but due to space limitations, I’m omitting that discussion in this piece.

Before proceedings to the Court’s reasoning, rebuffing the above argument, it is first necessary to understand how Section 499 works in practice.

How the defamation law works

To take action, an aggrieved person is only required to demonstrate that the alleged defamatory speech was published “knowing or having reason to believe that such imputation will harm, the reputation of such person”. A court of law will take cognisance of such a complaint, once it is convinced that a prima facie case has been made out by the complainant and will issue a summons to the person responsible for publishing the allegedly defamatory words. Once the accused appears before court, the onus is on him to convince the court that the words were not defamatory because they fall under the ten exceptions mentioned in Section 499.

These exceptions aren’t particularly free speech friendly. For instance the first exception states “It is not defamation to impute anything which is true concerning any person, if it be for the public good that the imputation should be made or published. Whether or not it is for the public good is a question of fact.”

Thus even if a person is speaking the truth, the law still requires him to explain the public good in publishing such speech. Given the ambiguity of the phrase “public good” it is possible to argue that journalists are likely to self-censor in the public interest.

The remaining exceptions allow for good faith criticism of public servants, the conduct of persons touching any public good, true reporting of court proceedings, any good faith opinion on the judgment of a court or conduct of any witness or agent in court proceedings, a good faith opinion on the merits of a performance, a censure passed in good faith by person having lawful authority over another, any accusation made in good faith to a lawful authority etc.

In any case, it is important to note that a court hearing a complaint is not required to consider these exceptions at the time of taking cognisance of the offence and issuing a summons. This means that the criminal justice machinery is put into motion even though it may be apparent to the judge that the words which are allegedly defamatory are also true. It is up to the accused to come and make such a defence.

The Supreme Court’s googly on right to reputation

In the normal course of constitutional law, a fundamental right is the touchstone on which the legality of other normal statutory laws are tested. In the present case, the constitutional challenge was framed in a way to pit a person’s right to reputation (which is the object of defamation laws) against the fundamental right to free speech. Since the latter, enshrined in the Constitution, is theoretically and legally on a higher plane, it is the defamation law that would have to mould itself to fit the scope of the restrictions placed in Article 19(2) of the Constitution.

However, it appears the Attorney General argued that the ‘Right to Reputation’ is a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution and so this case became one of balancing the fundamental right to reputation with the fundamental right to free speech under Article 19(1)(a). Balancing two fundamental rights against each other is a more complex endeavour; both are on an even keel and one cannot be subjugated to the other. For example, between liberty and equality, how do you subjugate one to another? Both are important.

The more important question to ask at this time is when did the ‘Right to Reputation’ become a fundamental right under Article 21? Prima facie the very concept of a fundamental ‘Right to Reputation’ is an absurd concept and is a result of the reckless judicial expansion of Article 21. As per the Constitution, Article 21 merely states: “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law”.

How did the Supreme Court read in the fundamental ‘Right to Reputation” into Article 21? It did so by citing past precedents which highlighted the importance of reputation in a person’s life but none of these judgments actually elevated the right to reputation as a fundamental right.

For the benefit of our readers, I’ve provided links to all the Indian judgments cited by Justice Misra (at least 3 of these judgments are his own) and leave it to you to explain this business of Right to Reputation becoming a fundamental right.

(i) Kiran Bedi v. Committee of Inquiry and another ; (There is no mention of reputation being a fundamental right in this decision);

(ii) Gian Kaur v. State of Punjab (The word reputation doesn’t even appear in the judgment although Justice Misra claims that this judgment says “the right to reputation is a natural right”);

(iii) Mehmood Nayyar Azam v. State of Chhatisgarh and others (This is Justice Misra’s own judgment where he makes the argument that reputation is a facet of Article 21 - the reasoning is vague);

(iv) Vishwanath Agrawal v. Saral Vishwanath Agrawal (This is Justice Misra’s own judgment. In this, even he doesn’t claim that reputation is a fundamental right);

(v) Umesh Kumar v. State of Andhra Pradesh and another (This judgment does say that reputation has been held to be a fundamental right under Article 21 in past precedents of the Supreme Court but none of the judgments that are cited actually said that reputation is a fundamental right);

(vi) Kishore Samrite v. State of Uttar Pradesh and others (This merely says reputation is important, nothing about it being a fundamental right);

(vii) Nilgiris Bar Association v. T.K. Mahalingam and another (This merely says reputation is important, nothing about it being a fundamental right);

(viii) Om Prakash Chautala v. Kanwar Bhan and others (This judgment by Justice Misra is the one where he proclaimed Right to Reputation to be part of Article 21 but with vague and verbose reasoning - please do read paragraph one).

Thus there is only one past case where Right to Reputation has been held to be a fundamental right to reputation and that is a judgment penned by Justice Misra himself, who is also the author of this present judgment. We are, of course, no closer to understanding why reputation has been declared a fundamental right.

It is important for a court to explain such reasoning because fundamental rights are the important rights in our legal system. They shouldn’t be trivialised and manufactured as per the whims of one judge or one bench. More importantly, what is the sense of declaring reputation to be a fundamental right when the entire aim of such rights is to curb the arbitrary exercise of state powers. Fundamental rights can only rarely be asserted against private individuals or private newspapers.

The final ruling

Once the court bought in its own priceless jurisprudence on the right to reputation being a fundamental right, there was little hope for success for the constitutional challenge. With not very convincing or detailed reasoning, the court concluded that Section 499 was constitutional since it placed only reasonable restrictions on free speech. I extract some of the reasoning from the final conclusions below:

“Reputation being an inherent componentof Article 21, we do not think it should be allowed to be sullied solely because another individual can have itsfreedom. It is not a restriction that has an inevitable consequence which impairs circulation of thought and ideas. In fact, it is control regard being had to another person’s right to go to Court and state that he has been wronged and abused. He can take recourse to a procedure recognized and accepted in law to retrieve and redeem his reputation.Therefore, the balance between the two rights needs to be struck. “Reputation” of one cannot be allowed to be crucified at the altar of the other’s right of free speech. The legislature in its wisdom has not thought it appropriate to abolish criminality of defamation in the obtaining social climate.”

Apart from the above reasoning, the Court also defends the constitutionality of Section 499 on the basis of the doctrine of constitutional fraternity and fundamental duty. Gautam Bhatia’ op-ed in the Hindu today explains why even that reasoning is perhaps flawed.

Balancing civil and criminal defamation laws

While it may have been unrealistic to expect the Supreme Court to entirely strike down Section 499, some were hopeful that it would at least downgrade it to the standards that were set in civil defamation for public officials in the Auto-Shankar case.

Traditionally, in civil cases, the defendant has had to prove that the allegedly defamatory comments were in fact fair comment or the truth. Genuine errors or mistakes would not be shielded under this standard. In recent years, there has been some genuine progress with both the Supreme Court and the High Courts raising the threshold for defamation claims by public functionaries.

As per the new standards, public functionaries will have to prove that the defamatory statements were made with malice. This standard was laid down by the Supreme Court in the Auto Shankar case and followed in the Money Control case. Unfortunately it has not completely percolated down to the lower judiciary as can be seen in the Zee TV case where the District Judge imposed damages of Rs. 20 lakhs on Zee TV for allegedly defaming three police inspectors who were convicted for encounter deaths in Connaught Place in 1997.

The standard under Section 499 for public officials does not require them to prove malice. The ‘Second Exception’ says “It is not defamation to express in good faith any opinion whatever respecting the conduct of a public servant in the discharge of his public functions, or respecting his character, so far as his character appears in that conduct, and no further”.

The problem with this provision is that the onus of establishing “good faith” is on the journalist. The burden of proof can make all the difference in such situations. Moreover since criminal courts look into the exceptions only after trial, it would mean that most accused will have to go through the criminal justice process before they can prove their freedom

Given the incongruous situation between civil and criminal law, it is no surprise that more lawyers prefer filing a criminal complaint because the threshold of proof under that law is lower than civil defamation.