Censoring the arts in 2017: advent of the NOC!

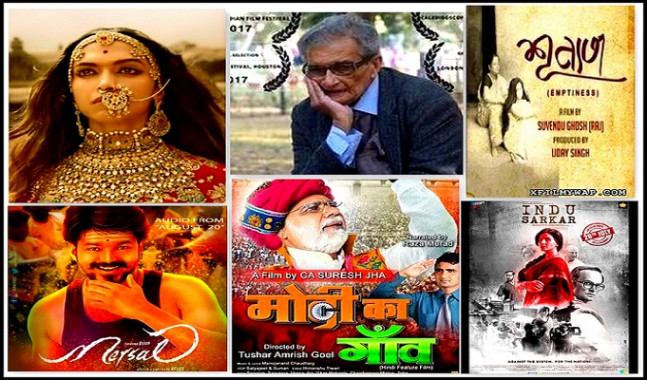

Clockwise from top: Padmavati, The Argumentative Indian, Shunyota, Indu Sarkar, Modi Ka Gaon, and Mersal

Film-making is challenge in a multi-religious, multi-ethnic democracy. Particularly if offence-takers are indulged. But each year the propensity to take offence, or to pander to offence-taking, seems to scale new heights. In 2017 the travails of film makers made news throughout the year.

The impetus for film censorship ranged from preserving social mores to socio-political and political considerations. Social and cultural groups with political backing stalled films, and even films that drew inspiration from current history made the certification body nervous. A new bar was set for acceptability: get a no-objection-certificate from those mentioned in the film before we permit you to show it!

As the mandatory requirement for certification translated into bald censorship, both historical and political subjects became anathema to a range of actors, from the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting and its certification arm, the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), to protestors on the street.

Padmavati’s travails

The abiding images and longest running headlines this year were about the film Padmavati. For a government and a polity intent on ‘upholding the honour of Hindu women’, creative imagination is an offence and such film-making demands intervention, which is an euphemism for allowing censorship both by mob and political fiat. You cannot allow a Muslim invader and Hindu queen separated by more than two centuries in recorded history and in poetry, to be brought together in fiction.

Much of 2017 was a roller coaster ride for the makers of the film. In January, the director was attacked and the sets destroyed. In February, the Shri Rajput Karni Sena (SRKS) demanded pre-censorship of historical films. March saw ministers of the Rajasthan state government pander to the Karni Sena, the Rashtriya Brahman Mahasangh and the Rajasthan Vaishya Mahasabha over their objections to the film.

Momentum against the film built up again in the last quarter of the year with the governments of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Gujarat saying they wanted Padmavati to be banned or have ‘objectionable content’ removed.

Cabinet Minister Uma Bharti joined the battle in November on Twitter asserting that the pride of the Indian woman was at stake. Rajasthan in particular remained the hotbed of protests against Padmavati with the Karni Sena, other local organizations and former royal families demonstrating publicly against it.

Mass demonstrations by Rajputs were also witnessed in Gujarat in November 2017. The BJP’s media coordinator in Haryana offered a prize of Rs 10 crore to anyone who would behead the film’s director Sanjay Leela Bhansali and actress Deepika Padukone and the Karni Sena threatened to cut off Padukone’s nose. Meanwhile as of the last week of December,

the censor board has asked the erstwhile Mewar royal family to join a panel to help certify Padmavati. And certification remained a receding goal.

Political discourse and censorship

The CBFC was particularly sensitive to content with references to political figures, words and events. For films like Modi Ka Gaon, Indu Sarkar and An Insignificant Man, the board ordered that the makers get no objection certificates from the politicians who were being referred to in the films.

Modi Ka Gaon is about Narendra Modi’s development agenda and is a tribute to his policies. The film makers were ordered to get a no objection certificate from Modi. Indu Sarkar is a reference to the emergency years under the Congress rule of Indira Gandhi while An Insignificant Man traces the rise of the Aam Aadmi Party and Arvind Kejriwal as a key leader of the party. In January, the CBFC had ordered the censoring of a reference to Rahul Gandhi in the film Coffee with D.

The CBFC was sensitive to references to current politics. The Argumentative Indian – a documentary about Nobel laureate Amartya Sen - has actually been denied censor board clearance because the film’s director refused to beep words like ‘Hindutva’, ‘cow’ and Gujarat’. The words ‘Patidar’ and ‘Patel’were beeped from the film Hamein Haq Chahiye Haq Se, which has many scenes reminiscent of the Patidar quota movement in Gujarat. And the makers of Power of Patidar (which was denied certification in 2016) wrote to the prime minister in 2017 and made other efforts to get it released, but to no avail. This too is a film on the same movement.

The trailer of the Tamil film Neelam about the Sri Lankan civil war was denied certification in October on the grounds that it could affect relations between the two countries. The trailer runs for about four minutes and 30 seconds: the filmmaker wondered how it could pose a threat to relations between the two countries.

Current affairs-related documentaries did not have a much better fate. The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting refused to allow the screening of three films at the International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala. These films, ‘In the Shade of Fallen Chinar’, ‘March March March’and the ‘Unbearable Being of Lightness’, covered issues such as the conflict in Kashmir, student agitations, and atrocities against dalit students.

Films which had references to current events such as demonetisation, GST and communal riots too faced a tough time getting censor approval. Mersal had references to GST and Shunyota to demonetisation.

Sharanam Gachchami was first denied and then granted certification. The film dealt with caste and reservations, highlighting atrocities committed in the name of caste. The director, Enumala Prem Raj, said the film referred to the suicide of Rohith Vemula, the flogging of dalits at Una, and the lynching of Mohammad Akhlaq at Dadri.

Violence accompanied censorship: before the film received certification, the Censor Board’s regional office in Hyderabad was ransacked by six students of the Osmania University Joint Action Committee who were later booked by the police.

The CBFC also refused to clear Colour of Darkness, a film about racial and caste bias in India and Australia, for public exhibition. The censor board opposed the differences between the English subtitles and the Gujarati dialogues. The dalit film director, GK Makwana, had to settle for a private screening.

Given the new heights of film censorship scaled by the CBFC in 2017,the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT)was kept busy. In the case of Modi Ka Gaon, Indu Sarkar and An Insignificant Man, it overturned the CBFC orders after the respective film makers appealed against the latter’s demands. It did not, however, permit the release of Power of the Patidar.

What the CBFC was allergic to

While the CBFC is a statutory body primarily responsible for certifying moving images, it censors words and references ceaselessly, as this analysis makes clear. In 2017 it had problems with the following:

- References to caste, government decisions like demonetisation and the implementation of the goods and services tax (GST).

- It wanted the words Patidar and Patel beeped from the film Hamein Haq Chahiye Haq Se.

- In Colour of Darkness it sought the removal of the word ‘most’ from the sentence ‘India is the most racist country in the world’.

- It demanded the removal of words 'saali', 'kutiya', and 'haraamzaadi' from ‘Hindi Medium’.

- In Toilet - Ek Prem Katha, it reportedly objected to a reference to bulls and a scene involving Janaeu, the white thread worn by Brahmins.

- CBFC was allergic to the words "Gujarat", "cow", "Hindu India" and "Hindutva" in The Argumentative Indian and wanted them muted.

- And because it demanded the removal of references to Mahatma Gandhi, ‘Bapu’ was replaced by babu.

- From Sameer, it wanted the words Man ki Baat to be removed.

- It also made headlines with its objection to the use of the word ‘intercourse’ in Jab Harry met Sejal.

Abusive language was a major issue, with the censor board disallowing such language in a string of films. Intimate scenes also did not pass muster, prominently in movies like Lipstick under My Burkha and Ka Bodyscapes. Lipstick under My Burkha was found to be too ‘lady-oriented’. The board also had a problem with its many sexual scenes and abusive language.

Scenes of smoking and drinking, violence against women, homosexuality and reference to caste were other grounds for censoring. Films like Sexy Durga ran into trouble with the censor board, forcing a change in the title to S. Durga. Despite the title change and orders of the Kerala High Court to screen the film at the International Film Festival of India, Goa, the film was not screened.

Ravi Jadhav’s Marathi film Nude was also denied a screening at the festival on the orders of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting , despite it being selected by the jury for screening.

Change of guard at the censor board

Given how controversial CBFC chairman Pahlaj Nihalani had become, the central government appointed a new chairperson, lyricist and advertising man Prasoon Joshi in August. But before he relinquished his post, Nihalani ended liquor consumption on screen, especially by leading men. Liquor bottles on display in frames were to be blurred as well. He argued that superstars are followed by millions and must set an example. In Munna Michael, Nawazuddin Siddiqui couldn’t be shown drinking though he played a gangster. The CBFC decreed that films showing alcohol consumption would get an A certificate.

Joshi’s tenure began with the banning of the film X Zone for graphic scenes of nudity, the trimming of love-making scenes in Ribbon, and the cutting of kissing and love making scenes by 50 per cent in the Hollywood film American Made.

Yet in the case of Andres Muschietti’s adaptation of Stephen King’s It, though the examining committee ordered cuts of visuals of horror and many profanities, Joshi stepped in to overturn all the cuts, including the profanities. Clearly the new chairman does not intend to be predictable.

SNAPSHOT

Issues on which Indian films were censored or blocked by CBFC or citizenry:

- Homophobia - Ka Bodyscapes

- Blind faith and superstition - MSG: The Messenger of God

- Distorting history - Padmavati, Games of Ayodhya

- Violence against women - Maatr

- Intimate scenes - Lipstick under my Burkha, Babumoshai Bandookbaaz, Begum Jaan, Baadhshaho, Bhoomi, Simran, Ribbon, Ka Bodyscapes, Aksar 2, Haraamkhor

- Obscenity - Judwa 2, Bhoomi,

- Abusive or objectionable language - Rambhajjan Zindabad, Bank Chor, Lipstick under my Burkha, Babumoshai Bandookbaaz, Rangoon, Anaarkali of Aarah, Begum Jaan, Maatr, Jab Harry Met Sejal, Kaalaakaandi, Bhoomi, Simran, Oru Pakka Kathai, Sexy Durga, Hindi Medium

- Showing a state in bad light - Jolly LLB, Indu Sarkar, Neelam, Haraamkhor

- Hurting religious sentiments - Sexy Durga, Muzaffarnagar - The Burning Love Anaarkali of Aarah, Sameer, Games of Ayodhya, Padmavati, Simran, Rong Beronger Kori

- Communal violence – Muzaffarnagar -The Burning Love, Begum Jaan, Games of Ayodhya

- References to political figures, words and events - Hamein Haq Chahiye Haq Se, Power of Patidar, Modi Ka Gaon, Shunyota, The Argumentative Indian, OK Jaanu, Coffee with D, An Insignificant Man, The Accidental Prime Minister, Indu Sarkar, Bhoomi, Sameer, March March March, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, In the Shade of Fallen Chinar, Games of Ayodhya, Ka Bodyscapes, Mersal

- Resemblance to real life events - Hindi Medium, Dhananjoy, Sameer, Sharanam Gachami

- Reference to caste - Toilet- Ek Prem Katha, Sharanam Gachami, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

- Scenes of smoking and drinking - Rangoon, Munna Michael

- Taboo subject - Phullu

- Language dubbing - Satyadev IPS

- Showing upper castes in bad light - Sharanam Gachami

Instances of censorship in the states

- In March 2017, the release of Satyadev IPS was stalled in Karnataka since the film was dubbed from Tamil to Kannada. Exhibitors and Kannada activists were against the entry of dubbed cinema in the state.

- In March 2017, the censor board’s regional office in Kolkata, West Bengal stalled the release of the demonetisation themed Bengali film Shunyota stating they could not agree on a certification category for the film, and referred it to the CBFC chairperson for a decision.

- In April 2017, the Dharohar Bachao Samiti vandalised the ad film set of Good Morning Films in Rajasthan because the makers were recreating a Pakistani city. The makers had apparently put up boards and signages of Pakistani locations in Urdu on temples.

- In June 2017, Bajrang Dal activists demanded a ban on sale of Kama Sutra books on the premises of the Khajuraho Temple in Madhya Pradesh. They argued it was against India’s tradition and culture.

- In June 2017 in Tamil Nadu, the Madras High Court was petitioned to pass a blanket order for suspending the screening of Priyanka Chopra starrer Baywatch. The petitioner argued that though the film had an ‘A’ certificate, its promos did not state so. As a result, minors could end up watching the film.

- In June 2017, the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting banned the exhibition of three documentaries at the 10th International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala. The documentaries were In the Shade of Fallen Chinar, March March March and The Unbearable Being of Lightness. The films were about the trouble in Kashmir, the JNU’s student agitation and the protests following the suicide of dalit scholar Rohith Vemula respectively

- In June 2017, the Directors Guild of Federation of Cine Technicians and Workers of Eastern India stalled shooting on the film Tui Shudhu Amar in West Bengal by refusing to allow technicians to work on the film. They claimed that that the production house was not following rules.

- Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath of Uttar Pradesh ordered in July 2017 that film songs and vulgar songs should not be played during the Kanwar yatra. Only bhajans could be played.

- Congress workers disrupted the screening of Indu Sarkar in Maharashtra in July 2017. Mumbai Regional Congress Committee chief Sanjay Nirupam wrote to CBFC chief Pahlaj Nihalani demanding to see the film before it was censored. A woman claiming to be Sanjay Gandhi’s daughter also sent a legal notice to the film-makers. Congress and BJP workers clashed outside a film theatre screening the film in Indore, Madhya Pradesh.

- In August 2017 the CBFC Kolkata, West Bengal withheld certification to the film Dhananjoy and referred the movie to the CBFC chairperson in Mumbai. No reason was given for the move, except that CBFC members could not reach a consenus. After the film was released, it was dragged to the Calcutta High Court through a writ petition. The petition alleged that the film was in contempt of court and involved character assassination of a victim who isn't alive to defend herself. The petitioner asked the CBFC to revoke certification.

- In August 2017, Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) threatened singer Mika for performing on Pakistan’s independence day in Chicago and Houston. MNS argued that the revenue generated from the event might fund terror activities against India. Mika had apparently tweeted that people join him in celebrating the independence day celebrations of India and ‘apna Pakistan’. The MNS organized protests and burnt Mika’s effigies in Maharashtra.

- The Jharkhand government in August 2017 banned Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar’s book The Adivasi will not Dance claiming that the book showed Santhal women in a bad light. The writer, a medical officer at a district health centre, was suspended from his job.

- In September 2017, the Supreme Court bench dismissed Mate Mahadevi’s appeal against the ban on the sale and circulation of her book, Basava Vachana Deepthi which was banned by the Karnataka government in 1998.

- In October 2017, the BJP government demanded the muting or deletion of scenes from the Tamil movie Mersal made in Tamil Nadu which contained scenes criticising GST.

- The movie Padmavati has been attacked by the governments of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Bihar and Gujarat. They want it banned or want ‘objectionable content’ removed. Rajasthan in particular has been the hotbed of protests with the Karni Sena, other local organizations and former royal families demonstrating publicly. Mass demonstrations by Rajputs were also witnessed in Gujarat in November 2017. The BJP’s media coordinator in Haryana offered a prize of Rs 10 crore to anyone who would behead the film director Sanjay Leela Bhansali and actress Deepika Padukone. The release of the film on December 1 has been stalled since the censor board is yet to give it a certificate.

- RSS-backed Hindu Jagran Manch vandalised the home of Games of Ayodhya director Sunil Singh in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh in December 2017.

- The Hindu Jagran Manch protested outside the regional CBFC office in Kolkata against the film Rong Beronger Kori which had characters called Ram and Sita.

- Some districts of western Uttar Pradesh did not screen Muzaffarnagar - The Burning Love.

PERPETRATORS OF CENSORSHIP

Government bodies

- Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC)

- Ministry of Information and Broadcasting

- Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT)

Courts

Supreme Court

Bombay High Court

Governments

- Governments of Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Gujarat

Religious and cultural groups:

- Hindu Makkal Katchi

- Hindu Jagran Manch

- Bajrang Dal

- Rajput Karni Sena

- Dharohar Bachao Samiti

Political organisations and politicians

Maharashtra Navnirman Sena

Congress

Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath

Bharatiya Janata Party

Suraj Pal Amu, BJP media coordinator in Haryana

Sanjay Nirupam, Mumbai Regional Congress Committee

Individuals and families

Woman claiming to be Sanjay Gandhi’s daughter

Writ petition and public interest litigation filed by individuals

Gangsters like Chota Shakeel

Professional bodies

- Directors Guild of Federation of Cine Technicians and Workers of Eastern India

- Association of Malayalam Movie Artists and the Film Employees Federation of Kerala

- Kannada cine artists and exhibitors

Production Houses

- Red Chillies Entertainment and Prakash Jha Productions

Internet companies

- Netflix, Amazon, Google, iTunes

Films Denied Certification in 2017

- CBFC yet to give certification to Padmavati

- S Durga release certification rescinded by CBFC

- CBFC yet to certify The Argumentative Indian

- CBFC refuses to certify Colour of Darkness

- CBFC denies certification to Tamil film Neelam

- CBFC denies certification to Power of Patidar

Censorship of events

- Information and Broadcasting Ministry refuses to allow screening of Sexy Durga/S.Durga at Mumbai Jio MAMI film festival. Also prevented the film from being screened at the 48th International Film Festival of India in Goa. Another film Nude was also not permitted screening.

Issue: The Minstry felt that the film title would hurt religious sentiments. The second film Nude is about a poor woman who works as a nude model for art students.

- Maharashtriya Navnirman Sena (MNS) threatens singer Mika for performing on Pakistan’s independence day in Chicago and Houston

Issue: MNS argued that the revenue generated may fund terror activities against India. Mika had apparently tweeted that people join him in celebrating the independence day celebration of India and ‘apna Pakistan’

- Right wing group Hindu Makkal Katchi wants arrest of actor Kamal Hasan and banning of reality show ‘Big Boss’ which he was hosting.

Issue: Hurting Tamil culture and promoting leftist and Dravidian ideologies; participants making obscene statements.

- PIL against Tamil ‘Big Boss’ reality show calling for its halt

Issue: Showed women in a pejorative manner and hurtful towards the downtrodden. Petitioner said his family was uncomfortable while viewing it because of the obscene behaviour and dress code of females on the show.

- I&B Ministry bans exhibition of three documentaries at the 10th International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala.

Issue: In the Shade of Fallen Chinar, March March March and the Unbearable Being of Lightness were the banned documentaries. The films are about the trouble in Kashmir, JNU’s student agitation and Rohit Vemula. Reason not stated in the order.

- UP Chief Minister Aditya Yoginath says film songs and vulgar songs not to be played during kanwariya yatra.

Issue: Only bhajans to be played, no film or vulgar songs.

- RSS-backed Hindu Jagran Manch vandalised home of Games of Ayodhya director Sunil Singh in Aligarh

Issue: The film was about a love story between a Hindu man and a Muslim woman at the time of the Babri Masjid demolition.

- Ad film set of Good Morning Films vandalised by Dharohar Bachao Samiti.

Issue: Its makers were recreating a Pakistani city in Rajasthan.

- Karni Sena vandalised the set of Padmavati in Rajasthan and assaulted director Sanjay Leela Bhansali.

Issue: Alleged that the film tarnishes Rajput honour.

- Information and Broadcasting Ministry bans the showing of condom ads from 6 am to 10 pm.

Issue: Unhealthy for children and can lead to unhealthy practices.

Upholders of artistic freedom

- Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) frequently overturned the decisions of the CBFC not to grant certification or censor certain films, eg: Rambhajjan Zindabad, Haraamkhor, Danish Girl, Lipstick under my Burkha, An Insignificant Man, Kaalakaandi, Games of Ayodhya etc.

- In April 2017, veteran actor Amol Palekar petitioned the Supreme Court arguing that pre-censorship is a violation of freedom of speech and expression and challenged censorship laws.

- In November 2017, the Kerala High Court ordered the screening of Sexy Durga at the International Film Festival of India, Goa. However, it was not screened because the CBFC cited a technicality over the change in the title.

- In June 2017, the Kerala High Court pulled up the CBFC for contempt and asked it to screen Ka Bodyscapes at its own expense for CBFC board members and issue certification to the film within a month. The CBFC had refused to comply with an earlier order from a Division Bench to grant certification to the film.

- Responding to a petition on the blanket ban of Priyanka Chopra Starrer Baywatch, the Madras High Court in June 2017 declined to stay the screening saying it was not inclined to pass a blanket ban when the CBFC had cleared the movie. The petitioner had argued that though the film had received an ‘A’ certificate, its advertisements failed to reveal this. The Madras High Court ordered that the police should ensure that minors did not enter the theatre to watch the film.