Censoring the prisons

In what is perhaps a fallout of the controversy around the now-banned documentary India’s Daughter, the Ministry of Home Affairs issued guidelines on July 24, 2015 "to regulate visits inside jails by individuals/NGOs/Company/Press for the purposes of undertaking research, making documentary or interviewing the inmates, etc.” The guidelines can be accessed over here.

The controversy over India’s Daughter had erupted because the documentary contained an interview of one of the convicted rapist’s in the infamous Delhi-bus gang-rape case in December, 2012. The interview of the convicted rapist took place in Tihar Jail and the rapist made some rather outrageous comments about women and how a woman was far more responsible for rape than a man. Predictably, the interview caused an outrage leading to the Home Ministry blocking the transmission or broadcast of the documentary in India.

A snapshot of the guidelines

The guidelines begin by laying down a general rule that “no private individual/press/NGO/Company should ordinarily be allowed entry into the prison for the purposes of doing research, making documentaries, writing articles or interviews etc.”

It then lists a series of exceptions where such interviews or research may be allowed if the government feels that the object of the research or interview would create a “positive social impact” or if the work relates to “prison reforms”.

Even in such a case, the prison authorities have been advised to follow certain stringent conditions which include requiring a security deposit of Rs. 1 lakh by way of a Demand Draft in the name of the Jail Superintendent (unless exemption is granted for research studies undertaken by students).

Once permission is secured, the person conducting the research is allowed to take in only a “handycam/Camera/Tape recorder or any other equipment directly connected with the purpose of the visit” and no tripod or stand mounted equipment or papers/book/pen etc. would be allowed.

The person conducting the interview is also required to sign an under-taking agreeing to submit all footage or audio bytes, along with the recording equipment to the jail superintendent for a period of three days. The jail superintendent is then required to vet the footage or recordings and delete any portion that he finds to be “objectionable”. The guidelines also state that the final version of any “documentary, film, research-paper, articles, book” cannot be published without a “no objection certificate” of the government or prison authority. If any of these guidelines are flouted, the security deposit may be forfeited by the Jail Superintendent.

The legality of the guidelines

From a legal perspective, there are primarily two problems with these guidelines.

The first issue pertains to the power of the Central Government to issue such guidelines to the states and the second pertains to the constitutionality of such guidelines.

‘Prisons’ fall within List II of Schedule VII of the Constitution. List II is the state list and that means only states can legislate on their prisons. So technically, state governments are not bound by law to follow the guidelines issued by the Ministry of Home Affairs.

It is, however, very possible that state prisons may amend their manuals to incorporate these guidelines. Until these guidelines are included in the jail manuals of individual states or in rules drafted under the ambit of each state’s prison legislation, the guidelines will lack the force of law. It is important for journalists to understand that the guidelines by themselves lack the force of law and cannot be cited as the reason to deny interviews or visits to jails. A mere circular from the bureaucracy isn’t binding on citizens unless its legitimacy can be traced to a law enacted by either Parliament or a state legislature.

Presuming that these guidelines are incorporated into state prison manuals, the question then arises as to whether the substance of these guidelines will survive a constitutional challenge. The issue has been addressed in a few Supreme Court judgments referenced by the guidelines themselves.

For example, in the case of Prabha Dutt v. Union of India, the petitioner who was then the chief reporter at the Hindustan Times was denied permission by the Delhi Government and the Superintendent of Tihar Jail to interview the notorious death row convicts, Billa and Ranga. In that case, the Jail Manual did allow death row convicts to meet relatives, friends, etc. but would not be allowed newspapers. In its infinite wisdom the court pointed out that the manual, however, did not expressly ban newspapermen and since there was no express ban against newspapermen, journalists, who in the court’s opinion could be classified as friends of society could conduct the interview.

The court, however, also left the door wide open for interviews to be denied in some cases without specifying the circumstances of such a denial. As is often the case, the Supreme Court missed an opportunity to develop some sound jurisprudence to inform future courts faced with a similar question. Another example of a prisoner communicating with the outside world would be the ‘Autoshankar case’ where a Tamil weekly was allowed to publish a convict’s autobiography, written while in jail.

Case-law aside, it would appear that on just first principles, most of these guidelines would be struck down as unconstitutional for not only imposing unreasonable restrictions on free speech but also for imposing prior restraints on free speech. As a thumb rule, all speech is considered free unless curbed and the onus is on the government to provide reasons for imposing restrictions on free speech – the onus can’t be put on the citizen to justify his free speech right.

These guidelines do exactly this by generally curbing free speech related to prison interviews, unless it can be shown that the research is intended for ‘creating positive social impact’ or related to ‘prison reforms’. Further, when imposing reasonable restrictions the State has to justify the restrictions on the basis of the permissible restrictions in Article 19(2) such as ‘public order, sovereignty of India, security of India, defamation, morality or decency, contempt of court, incitement to an offence’.

The State cannot, as it has in this case, ban journalists and others from visiting jails simply because “private individuals/documentary makers have accessed the prisoners un-authorizedly or have misused the permission for their own benefit”. Misusing permission for “their own benefit” is not a permissible ground to curb free speech restrictions.

Similarly, the conditions imposed by the circular to regulate the conduct of an interview also appear to be unconstitutional. Under Article 19(2) the State can impose reasonable restrictions to curb free speech but these restrictions must have a rational nexus to the ultimate aim of such a restriction and must also be proportional.

In the context of prison visits, the prison authorities can reasonably curb the entry of machine guns, bombs, knives or any other tool that may aid a prisoner to escape. But banning tripod stands for cameras, books and pens is downright unreasonable. What could be the possible reason to ban these items?

Similarly, the power of the prison department or the home ministries of the state/UT to vet the footage or recordings and delete ‘objectionable’ portions is a stunningly vague. What exactly is ‘objectionable’? Equally ‘stunning’ is the requirement that the final product, be it a documentary movie or a research paper or a book not be released or published without a “no-objection certificate” of the state government or prison head of the UT, as the case may be.

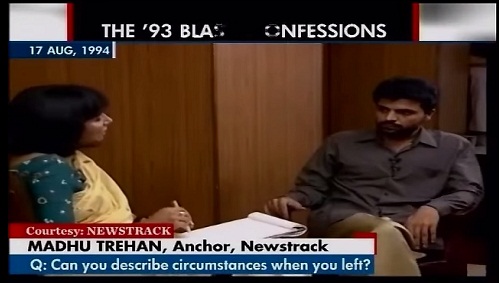

The only TV interview available of Yakub Memon took place because permission was given to interview him while in CBI custody. Journalist Madhu Trehan interviewing him for Newstrack.

Prior restraint is not permissible

Both these restrictions amount to “prior restraint” on free speech. The Supreme Court has made it clear in cases like Rajagopal v. State of TN that prior restraints are not permissible. Sure, the Censor Board does exercise such powers in the context of film censorship but even those powers have never been vested in bureaucrats.

More importantly, “prior restraints” have never been recognized under Indian law in the context of the printed word. Why should a student of sociology be required to get his paper on prisons and Foucault vetted by the Superintendent of Prisons just because he’s interviewed some prisoners for the paper?

Cases like the Sahara v. SEBI case have implied the legality of ‘prior restraints’ by allowing the postponement of publication of news which may affect an ongoing trial. The justification in such cases is that the publication may impair the rights of the accused to a fair trial. With regard to the present guidelines, how exactly does the Ministry of Home Affairs expect to justify the prior vetting requirement?

To answer this question we have to go back to the objective of these guidelines and as already discussed above, the Ministry hasn’t really identified the objectives of these guidelines – apart from some mumbo jumbo on some private individuals misusing permission for their own benefit.

To conclude, even if the guidelines are given the force of law – a court will most likely strike it down as unconstitutional.

Does the Home Affairs Ministry need a new legal brain?

To put it mildly, these guidelines are partly draconian, partly silly and partly bizarre. Why the ban on books, papers and pens? What are the criteria for a Jail Superintendent to decide “objectionable” material? Like the notification against Greenpeace’s Priya Pillai, this venture of the Ministry may be struck down as unconstitutional.

These guidelines are yet another example of how our civil service bureaucrats are hard-wired to rule as mini-dictators rather than govern as civil servants. The bureaucrat who genuinely believes in fundamental rights is a rare gem.