Falsely implicated by a newspaper

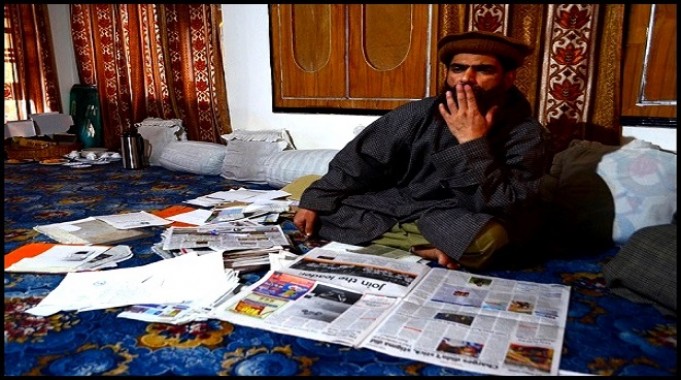

Rafiq Shah at his home with the clippings he has saved. All photos by Muzamil Mattoo

Srinagar: After spending more than 11 years there, Mohammad Rafiq Shah, one of the three Kashmiris accused in the 2005 Delhi bomb blast case, walked out of Tihar jail on February 16 2017. Shah, then a 22-year-old postgraduate student of Islamic Studies at Kashmir University, was arrested from his home on the Srinagar outskirts on a cold night in November 21, 2005, on charges of bombing.

The 33-year-old Shah, along with another Kashmiri, Mohammad Hussain Fazili, a shawl-weaver, were set free after additional sessions judge, Reetesh Singh, acquitted them of all charges. “It is manifestly clear that the prosecution has been unable to prove that it was Mohammad Rafiq Shah who had placed a bomb in the DTC bus bearing registration number DL-1PB-2719 on October 29, 2005. On the other hand, the plea of alibi raised by him seems to be probable. Thus in any event Mohammad Rafiq Shah deserves to be acquitted,” the court said.

Sixty-seven people were killed in a series of blasts that rocked India’s national capital in October 25, 2005.

After the acquittal, like every other news outlet, Hindustan Times journalists requested an interview. Shah politely asked them to reach his home. He was not eager to get published in the leading English daily. Instead, he wanted to convey and express displeasure at the paper’s reporting 11 years ago.

Shah showed the journalists when they arrived the 2005 HT piece which unquestioningly showed him as a “bomber” who planted the bomb in the DTC bus. “Such reports galvanized public support against me for my 11 years imprisonment,” he told The Hoot.

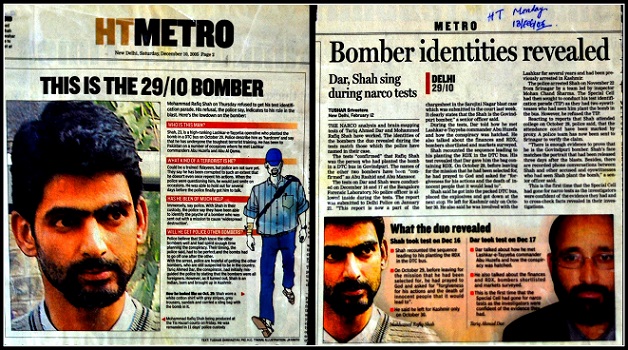

That 2005 report with the “bomber” photo has a sketch published in the HT on page 2 of the December 10, 2005 edition. At the bottom, the credit for the report was given to Tushar Shrivastav and photographer H.C. Tiwari.

The report titled “This is the 29/10 Bomber” described Shah as a “high ranking Lashkar-e-Toiba operative who planted a bomb in a DTC bus on October 29 (2005)”. Quoting anonymous police sources, it described Shah as a “hardcore” who has undergone the “toughest terrorist training and has been to Pakistan on a number of occasions”.

The incriminating stories in the Hindustan Times

Lapping up the police version that fell apart after more than a decade, it described him as a “bomber” who was on “mission to create widespread destruction”.

Sifting through a bundle of newspaper cuttings, Shah pointed out another HT report published on February 12, 2006. That report, with the headline “Bomber identities revealed”, filed by the same reporter, said the narco analysis and brain mapping test “confirmed” that Shah was the bomber who planted the bomb in the DTC bus.

Rafiq Shah narrates his story

“During my imprisonment, I could not understand why Hindustan Times was writing against me. Indian Express and Times of India carried both sides of the story instead of relying only on police,” said Shah, while showing the 2006 Express story which quoted his university attendance issued by the then varsity’s Vice Chancellor.

A day before Shrivastav’s narco-analysis story in 2006, the Times of India, on its front page, said the “Delhi bomber' was in class on 29/10”. It said: “He (Shah) was even paraded as the bomber in the Govindpuri blast, though the claim flew in the face of Shah’s narco-analysis test. Could it be a case of harried cops, under pressure to show results, targeting an innocent boy? It's too early to tell, but the possibility can't be ruled out yet,” it said.

More than a decade after the police theory fell apart in court, Shah’s case illustrates how the media jumps the gun and trots out the official version.

Shrivastav, who has left journalism, explained his position but refused to be quoted on the record. The HT editor did not respond to e-mails asking for his comment up to the time this appeared in the Hoot.

Shah, who is mulling enrolling for a doctorate, is astonished at such “concocted” and “malicious” reports. “I refused my Test Identification Parade because I was shown to many people during police custody,” he said. But the HT report, based on anonymous police officials, suggested that this refusal “indicate (d) his role in the blast”.

“The report has my photo which the HT photographer clicked in police custody instead of Tis Hazari court. My father visited the HT Delhi office to meet the photographer and the reporter but he was told they are no more working with the paper,” Shah added.

Explaining how the media peddled false reports, he said he has visited Delhi only once, as a primary class student with his father. “But the HT trusted the police version without taking my side. The reporter could have talked to my family and carried their version. I was shown as having travelled to Pakistan not once but many times. It is a blatant lie,” he said.

After his acquittal, however, he said, the HT ‘proactively’ reported on his wrongful imprisonment. Shah was referring to his detailed interview, apart from a couple of stories by Abhishek Saha, a reporter based in Kashmir.

“Shah’s case is illustrative of how rogue units like the Special Cell have compromised India’s counter-terror operations through ineptitude and gross malpractice,” said a report in the HT with a joint byline on February 22, 2017.

Saha, who met Shah along with an HT photojournalist at his home, said; “I visited Rafiq Shah after his return to Srinagar. He told us about the HT report 12 years ago and expressed his extreme displeasure.” But Shah didn’t allow that grievance to “shadow” their conversation, he said. “When we reached at around 7 in the morning he offered both of us bowls of dry fruit before tea. He then gave us a long interview for print as well as a video interview,” said Saha.

Despite facing a hostile media, Shah has gentle words of advice for the press fraternity. “Don’t get used as a pawn. It is the responsibility of a journalist body to take cognizance of such false reports as it mars the credibility of this trusted institution,” he said.

His suggestion is not misplaced. Manisha Sethi, who is part of the Jamia Teachers' Solidarity Association (JTSA) which pointed out the role of the media in its 2012 ‘Dossiers of a Very Special Cell’ report, said that after a person is acquitted, the media does some “breast-beating” for a day or so, as was seen in Shah’s case, but lacks “self-introspection” over the kind of reporting that creates hype around a person and makes it difficult for an accused to secure bail.

“Rarely does one see questioning and as such we see a kind of very stenographical reporting. Every time there is an acquittal, there is breast-beating. Next day the media does the same reporting because they know they can get away with it. Of course we have exceptions, though,” she told The Hoot.

The JTSA report also observed that: “Part of the trauma of those arrested on such charges results from reporting in the press which is more often than not tilted heavily in favour of the investigating agency”.

Last year, a report on ‘Innocent Acquitted’ by Innocence Network India, led by former Delhi High Court chief justice A. P. Shah, said that “a section of the media plays an irresponsible and sensationalist role in reporting on terror crimes and arrests of suspects in such cases.

After hearing the harrowing stories of acquitted people, it pointed to the case of journalist Iftikhar Gilani, who was arrested in 2002. Gilani narrated that journalists outside his house were reporting that he had absconded when he was inside the house. “All this serves to demonize and condemn the accused even before charges have been filed, and renders the accused’s family vulnerable to social boycott and exclusion,” it said.

It went on: “The news media should function as objective institutions, and not as mere handmaidens of investigating agencies. It is a long established media ethic that reporters provide their readers and audience with both sides of the story - not simply the state version,” it said.