French terror

The Charlie Hebdo massacre will re-ignite the long running debate over free speech versus Muslim beliefs.

VIKRAM JOHRI reports on the clash.

With the killing of 12 people in the Paris terror attack, including ten journalists of the Charlie Hebdo magazine, a new front has opened in the brutal legacy of Islamic terror. This is not the first time that a cartoonist has been targeted by Islamic fundamentalists. The most famous case is of Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, which, in 2005, published cartoons of the Prophet Mohammad.

This earned the wrath of Muslims who believe that the Prophet cannot be represented pictorially. In the years since, the paper has received a number of threats and reports indicate that the newspaper has taken measures to tighten security after Wednesday’s attack.

Free speech has been a burning topic in Europe for some time now. Film director Theo van Gogh was murdered by Mohammed Bouyeri, a Dutch-Moroccan Muslim, in 2004 for collaborating with Somali-born writer Ayaan Hirsi Ali who has spoken fearlessly about the shoddy treatment of women in Islam, including the heinous practice of vaginal mutilation in young girls.

Incidentally, the title of the film which the duo produced, Submission, is also the name of an upcoming book by French writer Michel Houellebecq which envisages a France taken over by Islamist parties and in which Houellebecq sees himself observing Ramadan. In what looks like a portentous, if eerie, connection, the latest issue of Charlie Hebdo had a caricature of Houellebecq on the cover.

As the news of the Paris shooting spread, Indian media luminaries got on to Twitter to condemn it in the strongest terms. Articles tracing the origins and subsequent growth of the magazine were widely shared, and several users changed their profile pictures to an image that had the words “Je suis Charlie” (I am Charlie) pasted on a black background.

The debate in the coming days will trace the familiar trajectory of that loaded term “freedom of expression”. One memorable cartoon that was shared on Twitter yesterday had two pencils standing upright in a simulation of the World Trade Centre towers with a lone bullet, shaped like an airplane, coming towards them.

It was a poignant reminder of the threat that any articulation faces in a world where journalists expose themselves to grave dangers every day. The videotaped beheadings of James Foley and Steven Sotloff by ISIS only reiterate what has been said again and again: that violence cannot be an answer in the battle of ideas.

India has had its own history with gagging those who have spoken freely, and this list does not merely include the loony fringe. Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses was banned and there was much dithering by the West Bengal government over providing protection to Tasleema Nasreen after her Lajja sparked a furore in Bangladesh.

As for (supposedly) non-government protestors, they have managed to achieve a number of things, from exiling artist M.F. Hussain to getting US author Wendy Doniger’s works pulped.

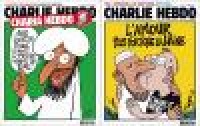

Charlie Hebdo had a history of taking on religion and had mocked Catholics, in particular the Pope, and Jews too. It had even come under the scanner of the French government for some of its provocative cartoons. In 2011, the magazine was firebombed and its website hacked after it published a cover with a Muslim man intoning: “100 lashes if you don’t die of laughter.” That man was Mohammed who was “guest-editing” the magazine.

The magazine’s response to the threats: a new cover the next week that had a Muslim man locking lips with a cartoonist to the caption, “Love is stronger than hate.”

The attack in Paris comes close on the heels of the Sydney attack which, of course, was the work of a sole, mentally disturbed man. What was newsworthy about that event was the Twitter hashtag #IWillRideWithYou, meant to reassure ordinary Muslims that Australian society stood with them. It was an offer from ordinary Australians to accompany their Muslim compatriots on public transport to protect them from any reprisal emerging from the attack on the Lindt Café.

It is this need to preserve the ideals of the Enlightenment that will come under increasing pressure in the days to come. Some might ask if Europe is at an inflection point. Massive protests against immigrants have gripped Germany over the past few weeks. Far right parties, such as UKIP in England and the National Front in France, have been gaining electoral ground. With the latest attacks, the debate over immigration and European identity will only get shriller.

In such a climate, humour and satire can both articulate and help us make sense of the big political debates of the time. Charlie Hebdo’s editor, Stéphane Charbonnier, who was killed in Wednesday’s attack, told Le Monde in a 2012 interview: "I don't feel as though I'm killing someone with a pen. I'm not putting lives at risk… What I am saying may be a bit pompous, but I prefer to die standing than live on my knees."

These words should provoke us to think. Free speech includes the right to offend. Where should practitioners draw the line between the right of free expression and deliberate provocation that endangers lives, including their own?

(Vikram Johri is a Bangalore-based writer. He tweets at @VohariJikram.)

Such articles are only possible because of your support. Help the Hoot. The Hoot is an independent initiative of the Media Foundation and requires funds for independent media monitoring. Please support us. Every rupee helps.