Great Supreme Court privacy ruling but…

The recent unanimous decision of a nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court in the case of Justice Puttiswamy v. Union of India, declaring privacy to be a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution has been received with much applause and rightly so. While the recognition of the fundamental right to privacy has undoubtedly strengthened the citizen vis-à-vis the state, this judgment may pose new problems for journalists, writers and filmmakers who report or write on the lives of public figures.

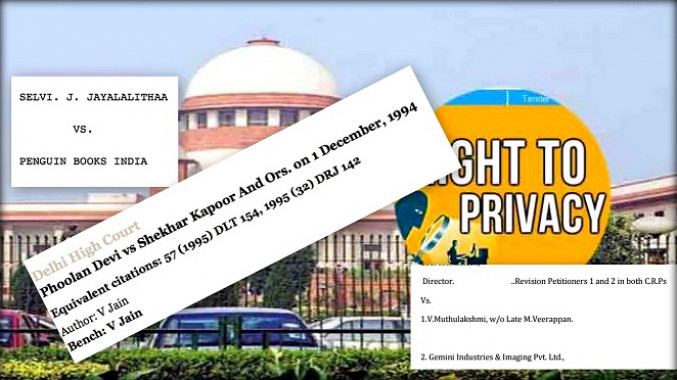

The conflict between privacy and journalism is not new and has led to litigation, especially after the Supreme Court’s judgment in Rajagopal v. State of Tamil Nadu, where the court detailed a very broad fundamental right to privacy. I have outlined some of this previous litigation in two pieces written for the Hoot and the Wire.

In the Rajagopal case, the point of contention was a legal threat by the state of Tamil Nadu against a newsmagazine seeking to restrain publication of a prisoner’s autobiography on the ground that it was defamatory to officials of the state. It is not clear how privacy was an issue in the case but the two judge bench went into detail on the contours of a very broad fundamental right to privacy.

The Rajagopal judgment defines privacy in the following broad terms:

“The right to privacy is implicit in the right to life and liberty guaranteed to the citizens of this country by Article 21. It is a “right to be let alone”. A citizen has a right to safeguard the privacy of his own, his family, marriage, procreation, motherhood, child-bearing and education among other matters. None can publish anything concerning the above matters without his consent whether truthful or otherwise and whether laudatory or critical. If he does so, he would be violating the right to privacy of the person concerned and would be liable in an action for damages. Position may, however, be different, if a person voluntarily thrusts himself into controversy or voluntarily invites or raises a controversy.”

The court does make some exceptions to this privacy right, including one particular exception, clarifying that public officials cannot assert a right to privacy for their official duties stating “In the case of public officials, it is obvious, right to privacy, or for that matter, the remedy of action for damages is simply not available with respect to their acts and conduct relevant to the discharge of their official duties.”

Notwithstanding the dilution of privacy right for public officials, there have been cases where public figures and public officials have asserted their right to privacy, on the basis of Rajagopal, to successfully restrain the publication or display of biographies or biopics of their lives.

Three such cases have involved Phoolan Devi, Jayalalitha and Veerappan’s wife, all of whom used the Rajagopal case to seek injunctions against unauthorized biopics or biographies. The first two succeeded in securing injunctions, while the third negotiated a settlement that involved deletion of certain scenes in a movie.

Jayalalitha managed an injunction because the court fell back on one particular paragraph in the Rajagopal judgment where the court held “….it must be held that the petitioners have a right to publish, what they allege to be the life story/autobiography of Auto Shankar insofar as it appears from the public records, even without his consent or authorization. But if they go beyond that and publish his life story, they may be invading his right to privacy and will be liable for the consequences in accordance with law.”

This paragraph basically disqualified any material not on the public record, which technically also means that personal interviews that reveal private information cannot be used. As demonstrated in the Jayalalitha case, those two lines from Rajagopal can restrain the publication of a biography and it doesn’t take much to extend this logic to regular reporting.

Privacy as a horizontal right

Fundamental rights in their essence were meant to be enforced by the citizen against the state (vertical application) and not against other citizens (horizontal application). For private litigation between two citizens, there are other rights based in statutory (legislation by parliament) or common law (judge made law). So even the fundamental right to free speech can be enforced only against the state’s attempt to curb speech.

One of the problems with Rajagopal is that it conceives of a very broad horizontal right to privacy. As per Rajagopal, “A citizen has a right to safeguard the privacy of his own, his family, marriage, procreation, motherhood, child-bearing and education among other matters. None can publish anything concerning the above matters without his consent whether truthful or otherwise and whether laudatory or critical.”

It is one thing to claim a strong fundamental right to privacy against the state but what is the logic of a fundamental right to privacy against fellow citizens? The judgment is silent on this aspect and as a result we have outcomes like the cases discussed above.

The Supreme Court missed an opportunity to clarify this issue in the Justice Puttiswamy case. In fact, there appears to be some confusion amongst the nine judges whether this right will apply horizontally. The joint judgment by Justice Chandrachud on behalf of 4 judges on the Bench endorses the definition of privacy in Rajagopal.

Similarly, Justice R. Nariman’s judgment endorses the definition of privacy in Rajagopal. By endorsing those particular paragraphs of Rajagopal, it appears that five judges endorse the view that privacy is a horizontal right that can be applied against private citizens and corporations.

However, Justice Bobde in his concurring opinion makes it clear that the fundamental right to privacy will apply only against the state while citizens can enforce only a common law privacy right against each other.

He states in the relevant part “Where the interference with a recognized interest is by the state or any other like entity recognized by Article 12, a claim for the violation of a fundamental right would lie. Where the author of an identical interference is a non-state actor, anaction at common law would lie in an ordinary court.” This is a reasonable distinction drawn by Justice Bobde.

A common law right of privacy has always existed in India. The principal difference between a common law right and a fundamental right is that the former can be curbed by Parliament and can be enforced only in a civil court unlike a fundamental right which cannot be curbed by Parliament and which can be enforced in a writ court.

Justice S.K. Kaul, on the other hand, is clear that the right applies against even private persons. He says, “The right of privacy is a fundamental right. It is a right which protects the inner sphere of the individual from interference from both State, and non-State actors and allows the individuals to make autonomous life choices.” The reference to non-State actors ensures that citizens can enforce their fundamental right to privacy against other citizens and not just the state.

This confusion does not bode well for the press since it has only a common law right to free speech against other citizens and when such a right clashes with the fundamental right to privacy, it is likely that the latter will triumph over the former. It is rather unfortunate that only one out of the nine judges sought to tackle this issue with the clarity that it deserved.

What about the privacy of public figures?

The second issue that the nine judges fail to discuss in detail is the definition of public officials. Does this include celebrities and public figures, not holding public office? What about the leader of a political party not holding public office? Or a public figure like Asaram Bapu?

As explained earlier, the Rajagopal judgment does state that public officials do not have privacy rights with respect “to their acts and conduct relevant to the discharge of their official duties.” The definition appears to exclude celebrities and public figures who do not hold public office.

At different points, some of the nine judges in Justice Puttiswamy v. Union of India do touch on the issue of public officials and privacy but they just end up creating more confusion. For instance, at page 89, Justice Chandrachud, writing on behalf of four judges, approvingly cites a precedent that discusses the problems of balancing the privacy rights of candidates for judicial appointments with the public’s right to know but does not provide any concrete answers.

At another point Justice S.K. Kaul makes the following sweeping statement: “There is no justification for making all truthful information available to the public. The public does not have an interest in knowing all information that is true. Which celebrity has had sexual relationships with whom might be of interest to the public but has no element of public interest and may therefore be a breach of privacy.19 Thus, truthful information that breaches privacy may also require protection.”

Whether a celebrity has had a sexual relationship with somebody can be of public interest depending on the circumstances. Why should the media not be allowed to report on it especially if the information is true?

Even more worryingly, Justice S.K. Kaul appears to have conflated the right to privacy with the right of a celebrity to control use of their name/image for commercial purposes. He states the following:

“Every individual should have a right to be able to exercise control over his/her own life and image as portrayed to the world and to control commercial use of his/her identity. This also means that an individual may be permitted to prevent others from using his image, name and other aspects of his/her personal life and identity for commercial purposes without his/her consent”.

Celebrities have always had a limited right, under common law, to control the use of their image and personality. So, for example, if a particular company decides to give the impression that a celebrity has endorsed their product they could be sued for the tort of passing off. The problem with Kaul’s judgment is that he has converted this erstwhile common law right to a fundamental right and widened it to give every individual (not just celebrities) the right to control the manner in which his life and identity is portrayed to the world, for commercial purposes.

In other words, anybody wanting to make a biopic or biography will have to take permission of the person if they intend to commericalize it. How will we ever have critical unauthorized biopics or biographies if the author has to seek permission before portraying the life of a famous person?

Since all the Justices have concurred with one another in a unanimous verdict, it is not possible to ignore Justice Kaul’s conclusion – his judgment is backed by nine judges.

The author is Assistant Professor, NALSAR