Immune to accountability

Public officers have been wrongly invoking exemptions under national interest to deny information under the RTI Act.

MANU MOUDGIL tracks recent RTI denials and the CIC~s approach in a two-part series.

The Right to Information (RTI) Act, which came into force on 12 October 2005, marked the evolution of India’s parliamentary democracy. The enactment of the legislation was the result of a persistent civil society movement which started in rural India to ensure right to work and livelihood to citizens through transparency in public works.

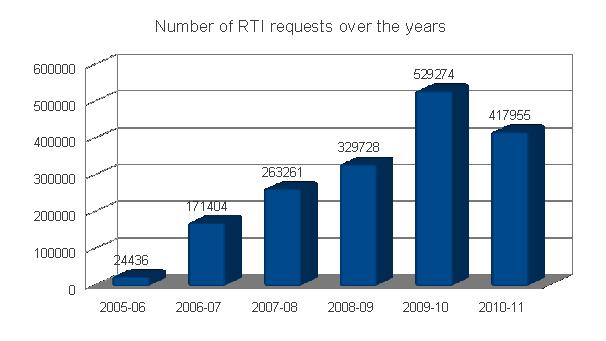

The Official Secrets Act, which labelled everything out-of-bounds for common public, was booted out and accountability got a new lifeline. Six years down the line there are no regrets. The most heartening fact is that people are increasingly arming themselves with the provisions of the legislation and turning India into a democratic country in its true sense. This is evident with the steady increase in number of requests for information filed with various public authorities from October 2005 to March 2011. The number of RTI applications with central authorities and Union Territories have actually gone up from 24,436 in 2005-06 to 4,17,955 by 2010-11.

However, there are still chores to be attended: provisions to be fortified, public officers to be trained and pendency to be dealt with. One of the sore points related to implementation of the RTI Act has been denial of information on the grounds of nation's security, strategic, scientific, economic and foreign interests. Besides, information can also be denied if it's related to any of the security and intelligence agencies exempted from the purview of the Act.

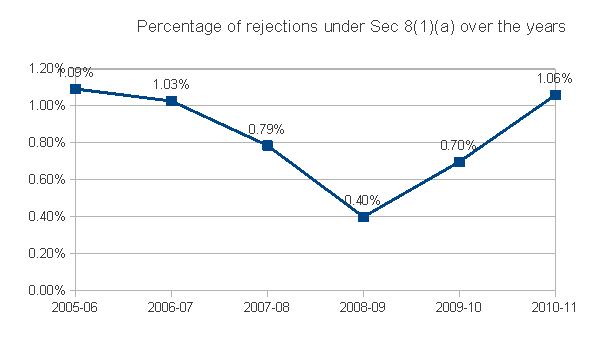

The misreading of these two provisions under Section 8(1)(a) and Section 24 is resulting in refusal of even that information which is not even remotely linked to nation's security, economic and other interests. Section 8(1)(a) debars disclosure of any information “which would prejudicially affect the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security, strategic, scientific or economic interests of the State, relation with foreign State or lead to incitement of an offence.”

However, an indepth analysis of the previous years' data reveals that the provision has been used by the public authorities as an ultimate weapon against free flow of information, thus negating the very purpose of the RTI Act.

While a total of 909 RTI applications were rejected by various CPIOs under Sec 8(1)(a) between October 2005 and March 2011, only 75 applicants had challenged the decisions by approaching the Central Information Commission (CIC) till December 2011, according to data compiled from case files available on the CIC's website.

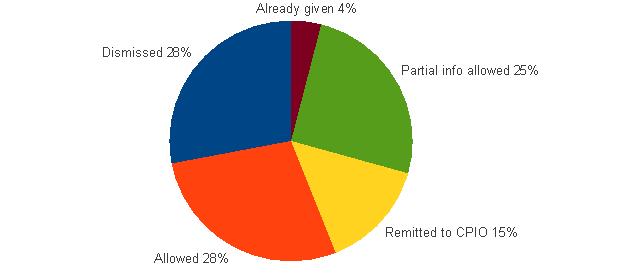

Of these, only 28 per cent decisions were found to be valid by the CIC thus

underscoring the fact that the approach of public officers in invoking Sec 8(1)(a) is doubtful. CIC overruled 21 of the decisions, asked the public authority to re-examine the matter in 11 while in 19 cases partial information was ordered to be given to the applicant. In three cases, the information had been given before the hearing took place.

Holier than thou

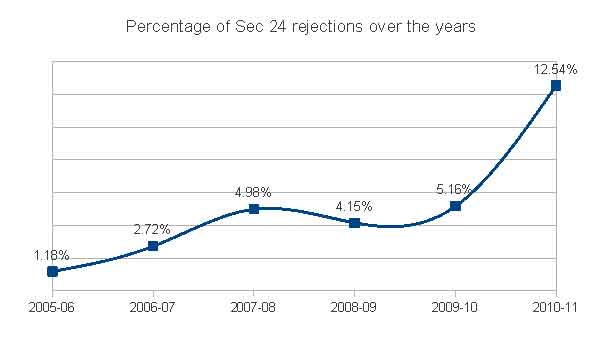

Under Section 24 of the RTI Act, certain security and intelligence organisations including the Intelligence Bureau, RAW, DRDO, CBI, Special Protection Group, Narcotics Control Bureau and a few paramilitary forces are exempted from providing information except when it relates to corruption or human rights violation.

However, these agencies tend to go overboard with the privilege by blocking even the information that they are duty bound to provide. For instance, the Advanced Technological Vessel Programme refused an RTI application seeking information on its labour welfare activities. It was only after an appeal was moved to the CIC, the authority was made to realise that the information can't hamper national security.

V K Mittal, a former scientist at the National Technical Research Organisation (NTRO), filed an RTI application seeking details about procurement of hi-tech gadgets by the organisation for which CAG had also found irregularities. NTRO denied the information citing the immunity granted under Section 24. The situation worsened when the agency even ignored the CIC's order to disclose the information. Later, the commission had to give a 10-day ultimatum to NTRO to provide the information or face necessary action.

That absolute exemption to these organisations is not in the right spirit of RTI has been recognised by the CIC time and again. While hearing appeal of Lt. Gen. S S Dahiya who had been denied information regarding certain vacancies and recruitment procedures in DRDO, the CIC recommended the Cabinet Secretariat to “review the absolute exemption granted u/s 25 (5) to an organisation such as the DRDO, specifically keeping in view that no such exemption is even granted to the Military authorities, the hard core of national security, so as to ensure that vital elements of management of the administration, notwithstanding the overriding demands of National Security & Intelligence, continue to conform to the spirit of the RTI Act.” Such suggestions have mostly gone unheeded and the list of exempted organisations have only swelled from the original 18 to 25 till the last count. No wonder the share of Section 24 in number of total rejections has gone up from 1.18 per cent in 2005-06 to 12.54 per cent in 2010-11.

The most recent inclusion of CBI in this exclusive list has raised heckles of RTI activists who argued that unlike other exempted agencies, which are primarily involved in intelligence gathering or national security, CBI is concerned with investigations. Besides, it could always lean on safeguards like Section 8 of the RTI Act to avoid divulging sensitive information and carry on with its task of exposing rather than getting involved in concealing.

CIC guards security secrets

Of the total 32 appeals related to security and strategic interests, 45 per cent of the rejections were upheld by the CIC. Only six appeals were allowed, 14 dismissed, partial information given in seven cases and five were remitted back to appellate authority for review. The metro pillar collapse was one such case in which CIC dealt with multiple exemptions.

Sudhir Vohra, a Delhi-based architect, had filed an application with Delhi Metro Rail Corporation seeking information on all structural drawings of both the pile foundation and the superstructure, including all steel reinforcement details, foundation details, engineering calculations and soil tests pertaining to the cantilevered bracket of Metro Pillar No 67 which had collapsed on July 12, 2009 resulting in the death of six persons and injury to many others.

The DMRC replied that the information sought was an intellectual property of DMRC and hence is exempted from disclosure under Section 8(1)(d) of the RTI Act. Later, the DMRC submitted that disclosure of the structural design would directly affect the safety and security of the Metro Rail system and thus would impinge upon the sovereignty and integrity of India thus evoking exemptions under Section 8(1)(a). It also added that disclosure can also impede the ongoing police investigation and hence invites exemption under Section 8(1)(h) as well.

However, CIC ordered that the argument for Section 8(1)(a) has been “over stated and logic over-stretched.” ”Disclosure of structural design of the pillar can not be held to prejudicially affect the sovereignty and integrity of India or its security and strategic interests,” it said. Though the contention for intellectual property right was accepted, CIC ruled that disclosure would be in the larger public interest since “placing the design of the ‘failed’ structure in the public domain may spur the authorities to develop a safer design for providing optimal security to the travelling public. Later, the DMRC challenged the order in High Court and ultimately in Supreme Court, which also ordered for disclosure of structural designs.

Another interesting case involved State Bank of India which had denied disclosure of videography done by a secret camera at one of its ATM. The applicant had sought the videography done on a particular date and time. The CIC mentioned that the recording should be exempted from disclosure because besides affecting the security and strategic interests, it could endanger life or physical safety of others and can also be used by the bank's competitors. However, the appeal was allowed in larger public interest because the applicant wanted to prove that the ATM machine malfunctioned at a particular time and no cash came out of it while the bank debited the amount from his account.

Most of the second appeals or complaints dismissed by CIC on security issue relates to information which can't be routinely disclosed. For instance, Lt. Col. (Retd) N.K. Ghai sought information on promotion process and on movement of armed forces officer. While the first part was provided, information on movement was denied on security grounds. The CIC upheld the denial saying that the movement of officers has a security implication, regardless of the purpose for which such visits would have been made.

Lawyer Ravinder Kumar sought information on ammunition issued to Delhi police officers during a specific time period. The PIO refused the application stating that the storage issue and use of ammunition are security related matters which can only be scrutinised by a designated agency, magistrate or through a properly instituted enquiry such as a judicial enquiry in specific instants where a prima-facie case of excessive use of force or misuse of weapons and ammunition is found to exist. The CIC upheld this contention.

In another case, Suchitra J.Y sought economic information related to a prototype fast breeder reactor under construction from the Bharatiya Nabhikiya Vidyut Nigam Ltd (BHAVINI), Kalpakkam . While information related to aggregate expenditure was provided, specific cost regarding fuel and core was denied which was upheld by the CIC saying “any information regarding costs will indicate what is happening inside the reactor and what its components are .”

It's evident that the CIC has been zealously trying to preserve the sanctity of the legislation which has given a new hope to India but the fact that only around 12 per cent of the refusals under Section 8(1)(a) have actually been challenged underscores the fact that not only the CPIOs need a better understanding of when not to impose exemptions, the applicants should also be willing to follow up the case till atleast the CIC level if not beyond.

In many instances, the commission has set standards for disclosure by passing comments and suggesting remedies on government's policies which come in the way of transparency.

(To be concluded)