Mangalore police defend action against TV reporters

Mangalore police go on the offensive with the arrest of yet another journalist in the homestay party raid case, ignoring protests by journalists that they were only doing their duty. Around ten days ago, Sharan Raj, a television journalist with Sahaya TV, was taken into custody by police on the same charges that were leveled against Naveen Soorinje of Kasturi TV. The TV reporter in the Mangalore homestay case, Soorinje has now spent over 60 days in jail. ACP T R Jagannathan, who is the investigating officer in the case, told this writer that the charges framed against both journalists was because they knew of the attack by the perpetuators.

“Soorinje had taken a videographer from TV 9 and Sharan, another videographer, also went to cover the raid. Sharan requested the attackers to show their face for the purpose of videographing it. After the telecast, the girls and boys went through a lot of mental agnony. The entire incident was shameful for society,” he said, adding that Sharan was also present during the pub attacks in 2009, when activists of the local Shri Ram Sene launched a raid on a pub ‘Amnesia’ as they felt pubbing was against ‘Indian’ culture. They assaulted the youth, pulling the girls and dragging them out.

Soorinje was arrested on Nov 9, 2012, and police have charged him under Sec 13, of the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, under sections of the Indian Penal Code includingunlawful assembly [IPC section143], rioting [147], rioting with deadly weapons [148], criminal trespass [447], house trespass [448], wrongful restraint [341], voluntarily causing hurt by dangerous weapons or means [323/324], criminal intimidation [506], intentional insult with intent to provoke breach [504], assault or criminal force against women with intent [354] and dacoity [395] and under sections of the Indecent Representation of Women Act.

Soorinje, who telecast a report titled ‘Talibanisation of Mangalore’ stated that he had got some information of a protest outside the homestay ‘Morning Mist’ and went to the spot to verify it. He didn’t initially see anything amiss but when 30 people barged in and began beating up the youth, he called a local inspector, Ravish Nayak, but couldn’t get through. Sharan entered with the attackers and along with other reporters came to the spot and began filming the raid.

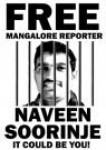

Soorinje was taken aback when police charged him along with the attackers and was arrested in November. Journalists organisations in Karnataka, the Mangalore Union of Journalists, and the Karnataka unit of the People’s Union of Civil Liberties investigated the entire incident and have protested the charge against Soorinje and his subsequent arrest. Since then, there have been numerous petitions, protests and campaigns, including a protest lodged by the Editors Guild of India against his continued incarceration, but to no avail.

Soorinje filed a bail application before the Karnataka High Court, but this was rejected by Justice Keshava Narayana on December 26, 2012. Soorinje is currently in hospital for treatment of chicken pox.

Why no bail for Soorinje?

Why are the authorities so averse to granting bail to Soorinje?

Both Soorinje and Sharan have been arrested on serious charges of unlawful activities, rioting and insulting women. Inexplicably, they have also been charged with possessing ‘unlawful’ weapons - do they mean the camera the video journalists had?

According to Mr Jagannathan, the charge-sheet in the case was filed in September last year and the court issued summons thrice to the accused but it was only after the third warrant that Soorinje was arrested. The police went on the basis of a complaint filed by Vijay Kumar, the host of the homestay party. Incidentally, the latter has gone on record before a PUCL investigating team that police made him sign a blank sheet and that the homestay attackers would have raped the girls but for the presence of video cameras.

Yet, the judge maintained that there was no difference between Soorinje and the attackers!

Soorinje’s lawyer, S Balan, argued that Soorinje had not asked any girl’s face to be uncovered for videographing purposes. He had tried to inform the police of the raid and was actually a whistle-blower. Besides, the police charge-sheet lists him as an absconder but he was very much present in Mangalore and had attended several official functions and programs.

None of this cut any ice with the judge. The government pleader argued that Soorinje and other accused had ‘assumed the role of civil police’ and were trying to create an atmosphere of fear in the minds of the public and use media publicity for this purpose. The repeated telecast of the videos had caused more damage than the actual injury caused to them and said their release was not in public interest as there was a likelihood the accused would indulge in similar activities if they were released on bail!

Rejecting the petitioner’s plea that Soorinje was a whistle-blower, the judge said that the statement of witnesses maintained that he had come to the homestay along with the group of attackers. Moreover, being a representative of the media, he should have prevented such an incident but, ‘prima facie, appears to have encouraged the happening of the incident and helped in videographing it and facilitating the telecast in television channels, causing great damage to their dignity and reputation’.

Moreover, the judge felt that the atmosphere of fear generated after the incident meant that the accused, including Soorinje, could threaten the witnesses and the bail could not therefore be granted.

Inexplicably, the judge heard two petitions for bail together – the first from Venugopal and Taranath Alva, who are accused nos. 6 and 7 in the homestay case and the second from Naveen Soorinje, who is accused no 44 in the homestay case. Reserving much of his ire for the former, the judge said they indulged in ‘bench hunting’ and were therefore ‘not law abiding citizens who would take the law into their own hands’ and the petitioners should not get bail.

Time and again, Soorinje said that he had gone to the site as he received a tip off, much as any other journalist would have done. Time and again, he has said that he tried calling the police too, though informing the police is not strictly the job of a journalist who is covering a crime. The journalist, in such a situation, can call up the police to ask for more information or even to find out if the police is aware of the crime being committed and what action it is taking. But to arrest him for covering a crime and continue to keep him in jail for alleged failure to tell the police really demonstrates a poor understanding of the role of the journalist.

Moreover, the judge has stated that the repeated telecast of the footage of the raid and the attack on the youth had damaged their reputation and caused fear in the minds of residents of Mangalore. No doubt it did do so, but the decision to loop repeated footage was a task undertaken in the studios and news-rooms of the television channels, where, doubtless, senior editors vetted the footage and decided to run it, over and over again. No one seems to ask the question what happened to the filters that are supposed to be in place in situations like these. Has the News Broadcasters Association (NBA) taken any cognizance of this?

Clearly, it is the messenger at the very bottom of this news chain who pays the price for this media coverage.