Mumbai 1993 – in three stories

It was Friday and I was covering the Bombay High Court for The Daily, a lively tabloid owned by industrialist Kamal Morarka. We heard the first blast in the High Court’s press room. It was the Stock Exchange blast at about 1.35 pm.

Everyone said it was a gas cylinder blast at one of the eateries lining the crowded lanes of Hutatma Chowk. When I saw smoke billowing all the way up behind the buildings opposite the High Court, I ran in the direction of the smoke. The glass shards from the Stock Exchange Building were still falling. Terrorism had arrived close home.

The rest of that day is now history.

`The Daily’ had its office in 1000-sq feet premises on the first floor of a building in Colaba’s Wodehouse Road. This was the British legatee and very cosmopolitan Colaba, in southern- most Bombay, before it became Mumbai. The majestic Taj Hotel, the Radio Club, the Fishermen’s basti (from where Ajmal Kasab was to land on Mumbai’s shores on the evening of November 26, 2008), Café Mondegar, the smoky bakeries of the Causeway, and the sailors on their scooters and bicycles headed for Navy Nagar at the other end of the Road were our daily quota of sights and smells as we went to and from office.

We were a small team, barely eight or nine reporters as against the broadsheet newspapers, the Indian Express and the Times of India, which had much bigger teams. We were very young, hardly three of us in the editorial staff with more than five years’ experience. We, like the police, were exhausted with coverage of the December (1992) and January 1993 communal riots.

But The Daily’s reporters got all the three biggest news breaks on the blasts case.

March 12 was spent in the mad rush from spot to spot - 13 blasts in a day. Mumbai was ravaged, numb with shock. That evening, Mumbai had lost its tongue. There was eerie quiet all round…

The next few hours, days were blurred…. Little sleep, back to the office…the rounds of the police stations, hospitals, the crime branch, any any any cop, absolutely any source, who would tell us what, where, why. We scrounged, we pleaded, we despaired. No policeman in his right mind would pick up our calls, forget talk to us. WHODUNNIT?

It was, I think Monday, March 15. We had THE STORY. The Mumbai police were stationed in a flat in Mahim in the Al Husseini Building, metres away from the Mahim police station.

Joaquim P. Menezes, my colleague, an energetic reporter, had cracked it. The Memons had been found to have planned and executed India’s first mass killings and terror plot.

Several weeks later, Joaquim told me how he broke the story, undoubtedly the most important story of that year. He was an asthmatic, but very hardworking. Crime was not his beat. (He had wanted to be a priest. A chance writing assignment had brought him to journalism). He was a lucky reporter who was at the right place at the right time. But how he wrapped up a story of that magnitude in a day!

He had a friend living in the locality. She met him, I think on March 13, and told him the cops were swarming in every building in her area. Al Husseini was a fortress. It was like curfew time. If you stepped out of home, you were questioned by the police, asked for identity documents.

Joaquim went up to the building. I don’t know which day that was. The Maruti car that was abandoned by the terrorists at Worli with Rubina Memon’s papers had been traced to Al Husseini.

At the Mahim police station, sleepless policemen, at the end of their tether, were thrashing suspects in various cells. Joaquim, barely two years in journalism, was incredulous. What he gathered was this: Footsteps away from the police station, 12 vehicles - cars and scooters - had left from the garage of Al Husseini on the night of March 11, for a location where they were parked for the next ten hours or so. The cars were laden with military- grade RDX, something I had not heard of then. The policemen had been too casual or too tired to have noticed.

Joaquim had all the names of the family. Of course, he reported that none of the Memons were to be found.

Joaquim became a sensation. The newspaper, however, got hardly any kudos from journalists.

Joaquim migrated to Canada some years later and I lost touch with him.

* * * * *

Sanjay Dutt exposed and arrested

The bigger sensation was Baljeet Parmar’s story of April 16, 1993, a month after the blasts. `` Sanjay has a gun” the headline said, with Dutt’s gangly face to go with it. Bollywood’s stinking connection with the glamorous part of Mumbai’s underworld was exposed.

From Mahim, the attention focused on Bandra, a rich suburb boasting its gorgeous coastline and its glitzy homes, many of them occupied by film stars. Sanjay Dutt, son of a respected Congress leader and actor Sunil Dutt, had kept weapons at his Bandra home, including the forbidden AK- 56 which civilians are not allowed even with a licence.

Baljeet, who lived at Antop Hill in Central Mumbai, had been out for lunch on April 13, for Baisakhi, the Punjabi harvest festival. On his way to the office, he took a detour for Mahim police station. After hours of waiting, one senior officer, who was leaving for a meeting at the Commissioner’s office, told Baljeet, `` The name of the son of your MP friend is emerging.’’

From then on, Baljeet could not rest a minute. He made several calls to policemen and politicians. He zeroed in on Sunil Dutt, who was not the MP of his area. He found out that Dutt senior was in Hamburg at the house of Jay Ullal, the seniormost photographer of Stern magazine. Dutt usually stayed with him when he was in Germany.

Ullal picked up the phone but said Dutt senior was not in. (He was, Baljeet found out later.) Then the chase through phone calls to London and New York. Dutt would not come on the line.

The tension of holding back such a big story got the better of Baljeet and he took the managing editor, Phiroze Dastur, into confidence on April 15. `` I typed out the story late at night, when most of the sub editors had left. I could not afford to have it leak,’’ he says.

On April 16, the story hit. Sanjay Dutt called up Baljeet from Mauritius to complain about his father, about his unhappy youth, his feelings about the way his mother had been treated, etc.

The senior Dutt also called and told Baljeet he should never have published the story as he could not help his son with any alibi now. He said his son had become worth Rs one crore – his signing amount for the film Khalnayak - and now Baljeet had queered the pitch for him.

Three days later Dutt was arrested as he arrived at Mumbai airport, one of the most sensational events of the case.

Baljeet, however, chuckles at the best memory about the story. The day the story broke, a senior and famous lawyer called up Baljeet to tell him it was great work. Days later The Daily received a legal notice from the lawyer’s office on behalf of Sanjay Dutt, for alleged defamation. The amount demanded was Rs 2 crore.

`` I called him and asked him, `What is this? You had congratulated me for the story”,’’ says Baljeet.

The lawyer’s reply was. `` You are like my son. He is my client and a b*****d client.’’

Baljeet now runs a newspaper in Mumbai.

Key conspirator sits in police custody as the bombs go off

I had got a rather bizarre tip-off some days before Baljeet’s Sanjay Dutt story.

One Noor Mohammed Sheikh Gul Mohammed, who later became an accused in the blasts conspiracy, had been in the crime branch custody on March 9, 1993, three days before the blasts went off.

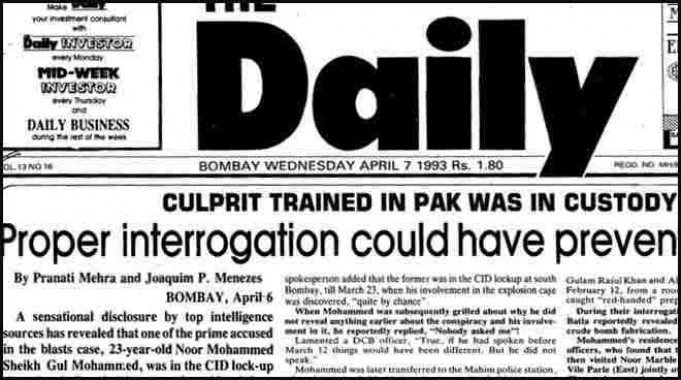

I shared the tip- off with my chief reporter, who suggested Joaquim join the story. We interviewed several policemen, and we filed this story, on April 6, 1993. It was published on April 7, under the headline: ``Proper Interrogation could have prevented blasts’’, and the slug:``Culprit trained in Pak was in police custody’’.

Gul Mohammed, a vicious rioter from Behrampada, had absconded in January 1993 and the cops were looking for him. They had kept a watch on his marble goods shop to nab him for his alleged involvement in the riots of the (preceding) December and January. He was suspected to have made crude bombs. The police did not know anything about his Dubai visit.

He had been recruited to go to Dubai for arms training by Tiger Memon and his accomplices some time in February of 1993. Gul Mohammad made that trip, and returned to India some time before March 9, to play his assigned role in the blasts conspiracy. A case of overconfidence. He returned to his shop on March 9, not knowing that the police were waiting for him. He fell into the hands of the Bandra police.

He kept his mouth shut about the Dubai trip.

He was formally arrested for the riot case and was taken to the Crime branch, CID. The police could not use their traditional methods to `interrogate’ him in custody on the night of March 9 and 10 because they were busy. On March 11, he did not squeal anything, though he was questioned.

The serial blasts went off one after the other on the afternoon of March 12. Gul Mohammed was in a crime branch lockup as the city moved from horror to horror.

* * * * *

The three stories quoted above were undoubtedly the biggest breaks on the case. Other reporters like Harish Nambiar also broke several stories on the blasts case, including Yakub Memon’s role.

Unfortunately I’ve not been able to get the clippings of either Baljeet’s or Joaquim’s story, despite trying at a documentation centre. Nor is there any confirmation that The Daily digitized these issues of the paper.

Some time in March 1993, I also broke the story of the involvement of local police and customs officials. Somnath Thapa, additional commissioner of customs, the most tragic figure of the story, had, on January 30 actually visited the landing points (Mhasla, Shekhadi) along the coast, where the contraband RDX and weapons were offloaded and yet failed to prevent the landings. RDX had been offloaded in Jan and February of 1993, on at least three separate occasions. He died of cancer in 2008, without being able to clear his name.

Thapa was the seniormost customs official accused in the case. R. K. Singh, assistant commissioner of customs and M. S. Sayyed, superintendent of customs, were the prominent ones among those accused of abetment in the crime.

The logistics of keeping the explosives hidden while Mumbai was in the midst of the worst-ever carnage in communal riots did not spook us reporters then. Years later as the trial progressed, with hindsight, we saw what Tiger Memon had pulled off.