Mumbai press swept aside demolition debris

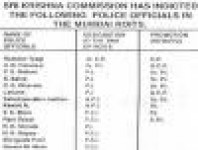

December 2012 was to be The month to remember 20 years of the demolition of the Babri Masjid and the ensuing Hindu-Muslim riots in many cities, specially Mumbai. But even before the Delhi gang rape took over the headlines, Ayodhya and Mumbai didn’t exactly dominate Mumbai’s newspapers. Described by the police as ``unprecedented’’, the riots had lasted five days in December 1992, and were followed by another round a month later, that lasted 10 days. Altogether, 900 citizens of Mumbai were killed in this violence, thousands injured, and lakhs worth of property destroyed. It wasn’t just the scale of death and destruction that made these riots unprecedented. Their reach made every Muslim feel vulnerable. Name plates of Muslims were removed from buildings in the poshest areas; some multinationals helped their Muslim employees shift to hotels. The riots also left a legacy that lasts till today -- a ghettoization in which both communities, but Muslims more than Hindus, prefer to live in `their’ areas. Mumbai was already divided, but not completely. Across the city, efforts were being made to escape the confines of one’s community. The riots brought these to a near-total stop. More ghettoes were added and existing ones expanded. Another event linked with the riots left a lasting impact: the Justice B N Srikrishna Commission of Inquiry into the riots. Its findings, indicting the Shiv Sena chief, became sensational because its Report was submitted and tabled when Bal Thackeray was the Supremo of the State – his party was in power. In a first, the Report also named 31 policemen as having acted communally, and recommended ``strict action’’ against them. The senior most of these had been the city’s Police Commissioner. The Commission’s recommendations became a matter of controversy for months; of litigation for years (the Supreme Court case to implement them is still on!). They were never implemented, but the Report became a handy weapon for the Congress to woo Given all this, there was a wealth of stories to be done to mark 20 years of the Mumbai riots. But going by the way the Mumbai papers covered them, it seems not. Of the seven English dailies published from Mumbai, only one – Hindustan Times – devoted two full pages and the main edit page piece to the riots in its December 6 edition. Mint Lounge, published by the same group, carried three related pieces in its December 8 edition, tracing the changes the city had gone through since the riots, and talking about the continuing appeal of the Shiv Sena – a topic largely ignored by the English press. The city’s largest circulated daily, the Times, carried just one piece in its December 6 edition – their third edit, by Bachi Karkaria. The paper is still remembered for its coverage of the 92-93 riots that earned it the ``abuse’’: `The Times of Pakistan’. Yet, 20 years later, the editor found nothing related to the riots worth carrying in its six city pages. Mumbai Mirror, the tabloid daily published by the same group, too had nothing on December 6. But in its December 7 edition, columnist Gautam Patel wrote about the Babri Masjid demolition and the Mumbai riots. And its Sunday edition on December 9 carried a story on Mumbai’s famous Irani restaurants, many of which had been attacked in the Shiv Sena belt of Dadar during the riots. The Indian Express’ Mumbai edition too had no mention of the Mumbai riots in its December 6 edition. For some reason, it waited till December 10 to carry an interview with senior advocate Yusuf Muchhala, who represented the victims in front of the Srikrishna Commission and has since been fighting in both the Supreme Court and the Bombay High Court to get the Report implemented. This was in its city supplement, Newsline. And it was only much later, on December 16, that the Sunday edition carried a two-page spread on Mumbra, the suburb that grew into a Muslim ghetto after the 92-93 riots. The DNA’s coverage was as lack-lustre as that of the Times – just one opinion piece on December 8, a letter to those born on December 6, 1992, on its weekly features page called `Jawjaw’. Interestingly, DNA was the only paper to carry a small report on December 6 on the month-long programme to be held in the city to commemorate 20 years of the riots, by activist groups. Surely this programme could have prompted some stories? The Free Press Journal carried an interview with Mark Tully about his experience of the demolition of the Babri Masjid, but nothing on the Mumbai riots. Finally, the Asian Age - like the others, no mention was made of the Mumbai riots in its December 6 edition, but two of its columnists, Javed Anand and Antara Dev Sen, devoted their columns to the riots and the demolition on December 8 and 9. The Times, the Express and The Free Press Journal were very much around when the riots took place, and much was expected from them 20 years after the event. On December 6, the TOI had a story on what Allahabad’s youth felt, but nothing on the generation that had grown up after the riots in Mumbai! It needs to be said here that in Mumbai, December 6 is important for another reason too. That’s the day Dalits from all over the State and the country congregate at Shivaji Park to pay homage to Dr Ambedkar on his death anniversary. Normally, that’s not big news, but this year, Bal Thackeray’s makeshift memorial in Shivaji Park made the impending Dalit mela hot news. But that should not have prevented the city’s press from carrying stories related to the 92-93 riots, specially when this time, there was another news angle - Sena chief Bal Thackeray’s death on November 17, just three weeks before December 6. He was the only leader named by the Srikrishna Commission as having directed his party members to attack Muslims during the riots. Sena involvement in the riots was anyway common knowledge; it helped the party capture the state two years later. Yet, a majority of the city’s papers chose to ignore this news angle. Could that be because this man identified with instigating part of the 92-93 communal violence, had just been given a state funeral, the government was afraid to touch his illegal memorial, and the press itself had eulogized him after his death? The Mumbai riots and the Srikrishna Commission Report have been treated as a ``dead issue’ for years now by the English press. Periodically, they make headlines, as in 2007-08, when the verdicts in the March 12, 1993 bomb blasts case started being handed out. The city’s Muslims grew angry that those who executed the blasts were being punished, while those responsible for the riots, which provoked the blasts, remained unpunished. This anger forced the riots into the city’s consciousness, and pressurized the government to take some action. But there was no such anger on December 6, 2012. Indeed, when this reporter went around meeting victims of the riots a week before their 20th anniversary, the latter asked bemused, ``Why have you come?’’ This was a mild reaction; there was also anger at having to retell a bitter story for no reason other than a reporter’s benefit. Over the years, whenever the Mumbai riots have suddenly become the focus of media attention, reporters have called this columnist asking for phone numbers of riot victims. After some years, the victims began conveying their distress at this unwelcome intrusion. Nevertheless, there are some victims who want their voices heard; some stories that still need to be told. But on the surface, they don’t always fit the bill. The basic requirement of reporters wanting to meet riot victims hasn’t changed over the years – the story isn’t worth telling if no one has died. This time, when I gave a TV reporter the name of a temple that has been attacked (I had earlier directed him to a Muslim victim, he now wanted a Hindu), the reporter asked: ``Did anyone die?”, and then, ``Was the temple completely burnt?’’ Finding both answers negative, he backed off. ``See, it could become a sensitive issue - we also want to convey harmony.’’ In fact, the pujari had told this writer a few years back that he held no grudge against any Muslim though Muslims had attacked the temple on the night of December 6. Muslims from the area continued to visit the temple. A perfect ``harmony’’ story! After years of meeting riot victims, I have reached one conclusion –if you have neither help nor justice nor friendship to offer them, making them relate their traumatic experience is cruelty. Does that mean that their stories shouldn’t be told? Surely the city needs to be reminded of a period when the government and the police looked on, and sometimes even connived, at the killing of innocents in the name of religion, specially when some of the main actors of that period are still in power? The press is notorious for reporting and forgetting. This norm applied to the riots too. In fact, the English press forgot the riots really quickly. Though it covered the proceedings of the Srikrishna Commission in the beginning, once the 1993 bomb blasts trial began in 1995, the Commission was ignored. The initial reportage of its proceedings revealed a lot about police functioning and attitudes during the riots. Had the reportage continued till 1997 (when the Commission had its last hearings), the myths of the riots that prevail till today, would have been dispelled. The prosecution of indicted policemen would have seemed necessary. Riot cases may have moved faster. Closed riot cases may have been re-opened. In fact, the government may have been forced to implement the Commission’s recommendations. By ignoring the Commission, the English press ignored those thousands of citizens who had suffered thanks to a communal administration, and helped grant the guilty immunity. This indifference carried on over the years. A direct result of this was the press’ depiction of the prosecution of indicted cops in 2001 as a step that would ``lower the morale of brave policemen only doing their duty in a dangerous situation’’. That lie has prevailed till today – of course only among non-Muslims, further widening the perception of the riots between communities. Indeed, the press has played a direct role in sharpening polarization between the city’s Hindus and Muslims both during and after the riots. But then, the press obviously doesn’t see promoting communal harmony on a continuous basis as one of its tasks.