Newton and Maoism: mass media finally gets it right

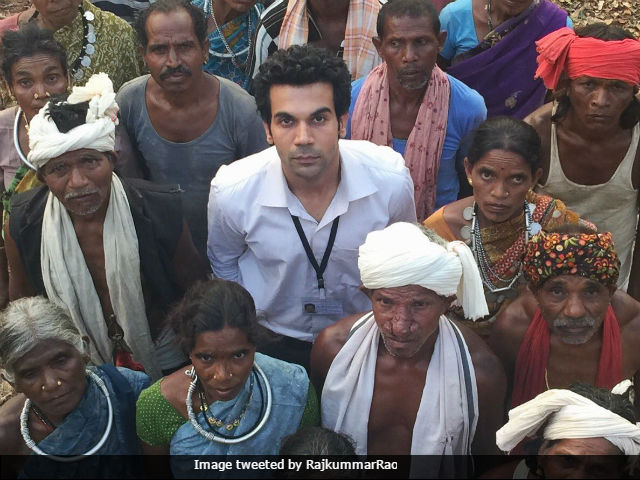

A still from Newton

There are no fiery dialogues in Newton. Though set in the badlands of Maoist Chhattisgarh, it depicts no grisly violence. Nor does it show red bandana wearing rebels lurking in the jungles and brooding darkly on the exploitation of marginalised people. Newton is a quiet film suffused with humour — and yet, it delivers a ringing satire on the nature of state intervention in Naxal areas and the sham elections that are held there. The film is, without doubt, Bollywood’s most telling critique yet of the way the country has fallen short in addressing the problems of tribal areas where Naxalism breeds.

Newton Kumar (Rajkummar Rao) is a young, upright government clerk who is sent to a remote village in Naxal-infested Dandakaranya to conduct the polls there. With his slightly ridiculous name (he changed his name from the effeminate Nutan to an ambitious Newton at the time of his school leaving exams) and his habit of blinking, he doesn’t look a likely hero. But he displays a steely resolve to do his job, notwithstanding the danger and the difficult terrain. The commandant of the company of security forces who is to help him and his electoral team, tells him that the area is unsafe and that no one would turn up to vote anyway. He offers to “arrange” some votes because this is how things are done in such areas. An angry and indignant Newton cites the rule book and insists on doing the 8-km trek deep into the woods in order to hold free and fair elections in a tiny settlement of 76 people.

They set up the voting booth in a crumbling school room in an abandoned village dotted with burnt out shells of huts. No one comes, probably out of fear because the Reds have boycotted the elections. The commandant and his men loll outside, waiting for the charade to end. Then a senior officer calls to say that he is coming with a foreign journalist who wants to do a story on elections being held in a conflict zone. At once the jawans go to the settlement to round up some people and herd them to the polling booth. If the media, especially the foreign media, are to be in attendance, India’s dance of democracy must be seen to be a jolly good show.

Though Newton is delighted that he is finally getting to conduct the polls, he soon realises that the tribals who have been brought across do not understand anything about the electoral process. They don’t know why they should vote or how it might benefit them. They have no idea that their elected representative is supposed to bring them the fruits of development. Nor that they have a right to demand bijli, sadak and paani. They stare blankly at the names on the voting machine, clueless as to which button to press since no politician has come here bearing even their empty promises.

In a scene of bitter irony, the villagers hold up their voter cards and inked fingers, and the foreign journalist and her television crew gratefully film them as proof of India’s much-vaunted, all-encompassing democracy.

Newton takes a swipe at the superficiality of the media and the ease with which we tend to swallow a story put out by the state, especially if the story relates to disturbed areas overrun with terrorists. However, director Amit V. Masurkar film is also a sensitive portrayal of the state’s response to people in those faraway Naxal-ridden jungles. Much of the film’s drama is centred around the tussle between Newton, the idealistic rookie government official, and the cynical, battle-hardened commandant, who is suspicious of every local person and regards all of them as potential Naxals. He epitomises the government’s contempt for the local people, and its callous, shrugging acceptance of their benighted state. As an agent of the state, he can facilitate democracy as a piece of ludicrous theatre, but he has really been put there to crush democratic values, thus perpetuating the endless cycle of deprivation and insurgency.

The Naxal movement, which started in West Bengal in 1967 and has since spread to Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra, has claimed tens of thousands of lives. This year too, 48 security personnel have been killed by Naxals in Chhattisgarh. Needless to say, mainstream cinema has attempted to depict the violent rebellion — and the state’s efforts to grapple with it. Films such as Prakash Jha’s Chakravyuh (2012), Ananth Mahadevan’s Red Alert: The War Within (2010), Mani Ratnam’s Raavan (2010), Sudhir Mishra’s Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi (2005) and many others have dealt with Naxalism.

However, where most films have either romanticised the issue or turned it into fodder for a Bollywood action movie, or done a bit of both, Masurkar’s Newton treads a different path. Here, the rebels are at a shadowy remove. What occupies centre stage is the failure of the state to engage with and address the plight of the local people, people who are caught between the extremists and the security forces, people who suffer from grinding poverty and exist on the ragged edge of civilisation.

A 2015 study published in the journal, Journalism Studies, by Bella Mody, Professor Emerita and former de Castro chair in Global Media at the University of Colorado, looked at how Indian media reported the Naxal issue. Examining five dailies in five language groups, it found that “more than 90 per cent of the articles on the Maoist movement in all five dailies were framed as individual episodes or events with no explanation addressing causes, remedies, or context. Description of the event was the common frame: who, what, when, where — no why.”

Although it is a mass media offering from the Bollywood stable, Newton manages to give us a sense of the ‘why’. With the gentlest of touch, it shows the probable flaw in the state’s approach when it comes to dealing with radicalised areas. When Newton enacts his own small rebellion and tries to push back against the brute force of an imperious state, the viewer is left in no doubt as to which is the better way. And the fact that he returns to the system and holds on to his scrupulous idealism suggests that there is hope for the country yet.

Shuma Raha is a senior journalist based in Delhi