Profitability is the only strategy

Book publishing is no longer an intellectual exercise as salability has gained precedence over new and controversial ideas.

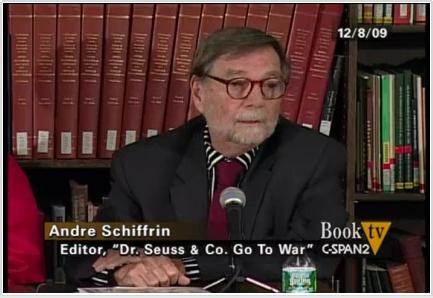

Excerpts from RAJASHRI DASGUPTA’s interview with Andre Schiffrin, veteran publisher and author.

A legendary figure in the publishing scene, Andre Schiffrin, founding director of not-for-profit publishing house, The New Press, was for 30 years the publisher of Pantheon in the US. He was the first to the introduce to the American readers, authors from Europe such as Michel Foucaut in 1965 at a time when it was difficult to even get an invite for him from universities. This was followed by publishing Jean Paul Sartre (rejected by a well-known publisher) and Simone De Beauvoir, and Gunnar and Alva Myrdal who were later to win the Nobel Prize for Economics, and, feminists such as Juliet Mitchell, Ann Oakley and Sheila Rowbotham. Andre Schiffrin, the author of The Business of Words, that has been translated and published in more than 30 countries since appearing a decade ago, was in Kolkata recently for a series of lectures. He spoke to Rajashri Dasgupta about how the marketplace of ideas in publishing has been replaced by marketplace for profits.

Q. Your book, The Business of Words, spells gloom and doom for the publishing world. Is this inevitable?

AS: I am not being pessimistic as I have been accused by some; I am being realistic. In fact, now readers tell me I have been too optimistic. In the last 10 years, publishing has changed specially in the English-speaking countries than in the entirety of the previous century.

We had assumed in the beginning that new ideas and different theories, whether non-fiction or literature, might lose money and that profits would come when it would reach a broader audience through book clubs and paper backs. We had thought if an idea was good it would sell, now an idea is good only if it makes money. This philosophy keeps away from ideology; only what makes money is valuable. There is little room for books with new controversial ideas or challenging literary voices. Everyone is looking for bestsellers it’s considered the locomotive that pulls the trade forward.

Q. Can publishers always introduce controversial ideas and take risks?

AS: When you don’t take risks you don’t get the surprises. New authors and new ideas always take time to catch on. There always have been publishers who make it a point to publish new authors. For decades, for example, we lost money on Foucaut for new ideas.

Q. Did you ever miss the opportunity to pick up a new idea?

AS: We were late in publishing books on the Vietnam War. I thought the war would be over soon since it was such a disaster. Other publishers, big and small, were much more far sighted and published books on Vietnam and South-East Asia. Finally, we chose the most scathing book on the opposition to Vietnam, Noam Chomsky’s American Power and the New Mandarins, and for years we continued to publish him.

Q. What has triggered the trend for rejection of ideas and new authors?

AS: This is because large international conglomerates have taken over an ever-increasing share of publishing in every country. In fact, the media industry is the second largest after aircraft industry in terms of the nation’s exports. The trend of mergers increase unabated; Random House has bought more than 20 publishers. But in the process, the new generation of small independent publishers is adversely affected. Bookstore chains are now demanding higher discounts from them, it threatens their very existence. This approach is fundamentally different from times when publishers believed in the marketplace of ideas as opposed to the market value of each idea or profits. The public was offered all sorts of ideas that were expressed without reservation.

Q. So the risk-taking venture has given way to books for profit?

AS: The recent changes in publishing demonstrate the application of market theory to the dissemination of culture. After the pro-business policies of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Regan, the owners of publishing houses view the market as a sort of ideal democracy. They argue that it is up to the readers to choose what they want even if it is frivolous and down market, and the elite should not impose their values on readers. The booming profits in publishing coffers are ample proof that the markets are functioning well.

But the marketplace is hardly a level playing field. Small publishers can hardly match big publishers that go in for commercially successful books. They have enormous funds for advertising, formidable sales force and network of press contacts. Books by small publishers are lucky when they find their books reviewed or displayed in shop shelves.

Earlier, most of the publishing houses were family owned, happy with 2-3 per cent profits linked to the cultural and intellectual life. They were aware that new fiction, prose, and poetry were bound to lose money. Authors would remain loyal to publishers who discovered them, and poaching was frowned upon. The idea that publishers should sell books only for profit was considered then banal. Publishing houses tried to widen boundaries and seek new readers and raise general levels of literacy and knowledge; now it’s either entertainment or hard information.

The new approach is that only books that will sell and make immediate profit should be published automatically eliminates a huge number of important books. Publishing boards decide what to publish-- not the editors ---with the financial and sales staff playing a pivotal role. As a result, editors understandably are less willing to take on a challenging book or new author.

Q. Isn’t the selective choice of books for profit a kind of censorship?

AS: It’s a censorship of kind, when you exclude certain ideas what society needs. New ideas and new authors take time to catch on and years before the author finds a large audience. Moreover, the market cannot be the judge of an idea’s value; thousands of great books have never made money. Traditionally, it was assumed that new ideas and theories would not reap in profits. In fact the phrase “the free market of ideas” does not refer to the market value of each idea; it means that ideas of all sorts should be put before the public fully, not in sound bites. With the strict control of profit and loss, editors are judged and evaluated, his/her salary depends on the salability of the book. That is why poetry etc., is out.

The way the publishing world is going I feel I am taking part in a geriatric version of Agatha Christie’s And then There Were None. Since the Regan and Thatcher times, everyone close to my age has disappeared, either early retirement or fired. The basis was financial consideration, since for less money younger people are willing to work. The effect was to erase completely corporate memory; those who remembered the way things were done were replaced by a group of people who automatically accepted the new dictates and ways as the norm.

Q. Are you implying that in the past there was no censorship?

AS: Of course not. History reveals many outrageous examples of editors refusing to publish certain books or influence what authors had to say. Let’s take for example Harpers that had published earlier works of Leon Trotsky. When Trotsky was murdered, his admirers found on his desk the blood splattered manuscript of his attack on Stalin. His admirers rushed the sheets to New York assuming the publishers would print it immediately.

But the then chief editor of Harper’s realised that the US would be at war with Germany soon and need Soviet Union as an ally. Though the editor was not under any pressure, he discussed the issue with his contact in the State Department and both felt it should be published at a more opportune time. Till the War ended, copies of Trotsky’s book that had already been printed were never sold. This decision was not borne by profits, it symbolised the “responsible” behaviour of elites, the right thing for a citizen to do even at the cost of the firm.

Q. Pantheon, at one period, focused on translating and publishing European scholars. There must have been readers....

AS: The witch hunt of the McCarthy era and the Republican goal that finally ended in 1954 had a devastating effect on American intellectual life. Dissent and progressive ideas almost disappeared and American voices were being marginalised and silenced. There remained a small pool of liberal scholars and journalists whom we could draw upon. We turned to Europe.

It also made good publishing strategy since most European authors were not under contract with US publishing units, and we did not need to invest too much funds or worry about profits. Because of this we could afford to look for authors that had been silenced, rejected, or neglected during the McCarthy era and revive the intellectual excitement in the country. There was excitement in publishing books like EP Thomson’s The Making of the English Working Class, the social and economic history of ordinary people that had never been written before; it was such a success it is still in print.