Ra-Ra Rajan: media and the Rajan effect

On June 18 Reserve Bank of India Governor Raghuram Rajan announced that he planned to return to his teaching job at the University of Chicago once his term comes to an end in September. It was stunning news, confirming as it did rumours that the government was not keen to grant him a second innings at RBI.

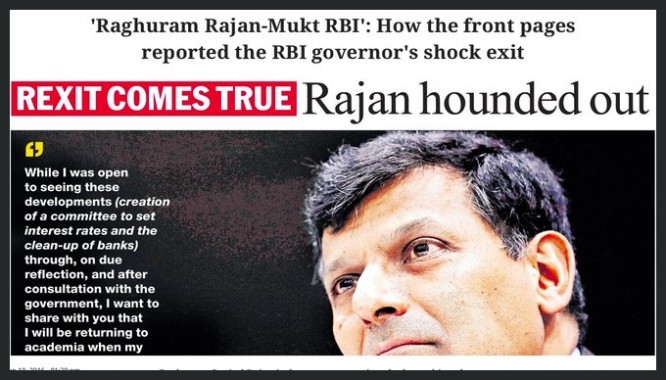

What was even more stunning perhaps was the avalanche of reportage and commentary on his departure that followed. The media already had a word for his probable exit — “RRexit" (a pun on “Brexit" or the UK’s possible departure from the EU, in case you’ve been living under a rock lately). And from headlines to hashtags, it was RRexit that loomed large over all other news.

There was something for everyone: gloom and doom at the prospect of Rajan giving up the reins of the country’s central bank; breathless paeans to the “rock star” Governor — he of the killer looks and “tall, lean frame”; acidic pieces on how the government had hounded out a first rate economist who was doing a fantastic job of managing monetary policy simply because he wouldn’t toe its line; more acidic pieces on why Rajan wasn’t all that he was cracked up to be; and of course, skillful arguments in defence of a government that silently showed him the door. In short, every aspect of his exit was picked up, parsed and pontificated upon.

But the mourning came first. No sooner did the news break, much of the media — print and digital — went into deep depression that come September, the man who enjoys tremendous respect and credibility as an economist at home and abroad, wouldn’t be there to steer the economy. It was as if India had pulled off defeat from the jaws of victory in a major cricket tournament — such was the outpouring of emotion on display. “Wrecks it”, howled The Telegraph, and went on to say: “Rajan hounded out”. Indian Express headlined the news as “Raghuram Rajan-mukt RBI” — a clever dig at the government which, though some distance away from its avowed goal of a Congress-mukt Bharat, had at least managed to rid the central bank of its much too independent Governor.

Others wallowed in hyperbole. “India’s debonair central banker Raghuram Rajan leaves behind many broken hearts and disappointed souls,” said one report in quartz.com (Broken hearts? Really?) Rediff.com referred to his “near-celebrity status.” Business Standard gushed: “…Raghuram Rajan is perhaps the most famous and important economist of our times.”

And of course there were reports aplenty on how Rajan’s departure would send the rupee, the stock, bond and money markets into a state of nervous breakdown. As The Times of India wrote solemnly, “The news sent shockwaves coursing through the financial and political capitals of India and, coming as it does just ahead of the Brexit vote, could trigger volatility in the stock, bond and currency markets.”

In the event, when the markets opened on Monday, none of that doomsday scenario came to pass. The rupee did fall, but the stock market took a dive only to bounce right back.

To come back to Rajan, never before has the exit of an RBI Governor sparked such a frenzy of prolonged media coverage. There is good reason for that, though. When the Manmohan Singh government appointed him Governor of the RBI in 2013, he was already something of a star in the international economics fraternity. He had served as chief economist of the IMF from 2003 to 2007, had a professorship at the University of Chicago, and in 2005 predicted the sub-prime crisis that hit the US — and global markets — three years later. He was in fact a world away from a stodgy senior bureaucrat bumped up to the RBI’s top job — as a lot of Governors had hitherto been.

Since assuming office, Rajan has tackled inflation, stabilised the rupee, waged a war on crony capitalism and bad loans by forcing banks to declare massive losses. He locked horns with the government on the interest rate, refusing to cut it as much as the government wanted, and choosing instead to keep his focus on containing inflation. Add to that the fact that he is devilishly handsome, media savvy, and came out with statements like “My name is Raghuram Rajan and I do what I do” — almost akin to “The name’s Bond. James Bond” — and you have a man who quickly became a darling of the media. They called him a “rock star” Governor, one who had put “sex back into the Sensex”.

Rajan’s exit was never going to be a non-event. (Though if you were only looking at the Hindustan Times’s skinny, anaemic lead story on June 19, you might have thought it was.) And this one was loaded with controversy, preceded as it was by BJP MP Subramaniam Swamy launching a series of broadsides at him, calling him, among other things, “mentally not fully Indian”. The government had allowed Swamy to continue to spew his vitriol and gave no clear indication of whether it wanted to keep Rajan on for a second term. “RRexit" was very much in the air when he finally put all speculation to rest and made his sensational announcement.

It was a media lollapalooza any which way you looked. And journalists and commentators had a field day, extolling him or bashing him — or bashing the government for letting this fine talent go.

As always, social media erupted in outrage, with journalists too tweeting their sarky comments. Shekhar Gupta tweeted: “Right call, Raghuram Rajan. Intellect & global respect is his capital. Why trade it for a chair in a tank filled with petty, mediocre sharks”. Others sneered that maybe the government would rather have the likes of Gajendra Chauhan or Pehlaj Nihalani as RBI Guv.

As the initial shock and awe of the news subsided, it was interesting to watch the commentary get sharply polarised. A Times of India editorial declared grandly that letting him go was “a travesty likely to recoil on the government”. In its sister paper, The Economic Times, Sugato Ghosh took the opposite view: “…the Governor has had his share of failures and was certainly not the best man to have occupied the 18th floor office of the Mint Street tower. But his visible earnestness, brilliant one-liners and forthcoming demeanour often masked the foibles of the central bank.”

Expressing the same sentiments far more elegantly and with greater coherence of argument, Rajiv Kumar wrote in The Indian Express that there were flaws in Rajan’s monetary policy. He said, moreover, that basically the governor had it coming because his policies were out of sync with those of the government and that as a central banker you had to work closely with the government. “Could Rajan, an excellent networker otherwise, have become a victim of excessive adulation from the community of fawning financial analysts and breathless media anchors who in their selfish interests made him into a prima donna who was beyond all established norms,” he asked.

That he had allegedly taken on the role of a “public intellectual”, choosing to speak out on tolerance, and choosing too to voice his skepticism over the government’s GDP numbers were cited by many as part of the reason for his downfall. Rediff claimed that his “near-celebrity status” and “media-management” skills had irked the government.

The RBI chief as media manager? Did Rajan really have the time to multi-task to that extent? If he did, more’s the reason the government should have retained him. After all, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government understands an awful lot about the manifold benefits of media management.

But seriously, in the deafening din over his exit and the sheer volume of commentary emanating from it, some pieces stood out. In a sharp article in Mint titled 10 Signals from Raghuram Rajan’s Exit, Manas Chakravarty said, “… the denial of an extension to Rajan indicates that what matters for the government is not the idea of central bank independence, but getting someone who will toe their line.” Chakravarty went on to say that the final lesson from l’affaire Rajan is that there can’t be two leading men in a film. “Rajan had acquired a huge following and commanded immense respect internationally. He was, as the media repeatedly said, a rock star. His exit signals that in India, there can only be one rock star. The rest can, at best, make up the chorus.”

Rightly or wrongly, Raghuram Rajan had declined to be part of the chorus. So he simply had to go. Sadly for the media, it will be a while before we get an RBI Governor as capable of bewitching both financial pundits and the financially clueless.

Shuma Raha is a senior journalist based in Delhi