Rajasthan's new ordinance may survive legal challenge

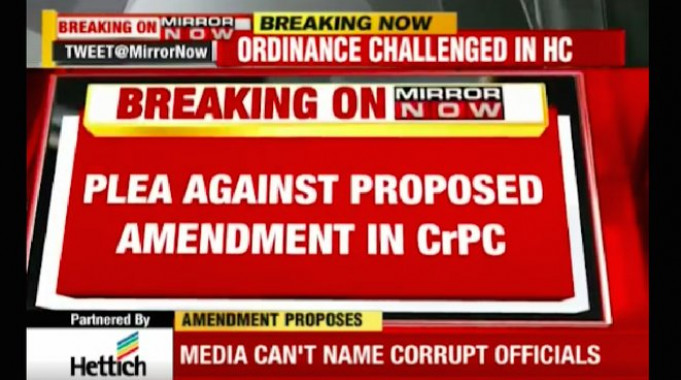

The Rajasthan Government’s new Ordinance amending the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 has sparked an outcry amongst the media for its provisions prohibiting the reporting of any criminal complaint or FIR against a sitting or retired judge or a public servant for acts committed done by them in discharge of their official duties until the state government has given sanction to the police or the magistrate to take cognizance of such an offence. As per the amendment, the government will have to grant sanction within 180 days of receiving a request for sanction or it shall be deemed to be granted.

The Ordinance simultaneously amends the Indian Penal Code (IPC) to insert a new Section 228-B providing for a punishment for those who violate the gag provision being inserted in the Cr.P.C. The punishment may extend to a period of two years and can also include a fine. The offending provisions read as follows:

S. 156(3) & S. 190(1): Provided also that no one shall print or publish or publicize in any manner the name, address, photograph, family details, or any other particulars which many lead to disclosure of identity of a Judge or Magistrate or a public servant against whom any proceeding under this section is pending, until the sanction as aforesaid has been deemed or deemed to have been issued

S. 228B: Whoever contravenes the provisions of fourth proviso of sub-section (3) of section 156, and fourth proviso of sub-section (1) of section 190, of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (Act No. 2 of 1974) shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to two years and shall also be liable to fine.

These amendments appear to be aimed at gagging the press from reporting about any corruption in the run up to the state elections in Rajasthan scheduled for next year.

The mechanics of the law - When does the embargo on reporting begin and to whom does it apply?

The usual tales of corruption or abuse of office by a public servant in India begins with a leak to the media, followed by public outrage, usually on social media, after which the police may initiate an investigation on its own or a magistrate on receipt of a complaint may order the police to initiate an investigation or a PIL before the High Court or Supreme Court results in a probe being ordered.

Given the above described chain of events the first question that we must ask of the Rajasthan Government is when exactly does the embargo on the reporting start? The proposed amendments by the Rajasthan Government, prohibits the reporting or publishing about public servants against “whom any proceeding under this section is pending, until the sanction as aforesaid has been deemed or deemed to have been issued”.

In the normal course of events, “proceedings” are deemed to have been initiated against a person when the police or a magistrate take cognizance of any offence and begin investigations or issue summons. Thanks to these amendments, the police or the magistrate cannot take any cognizance of such offence until the government grants sanction. For the government to grant sanction, a proposal for sanction has to be submitted to the state government. So, when exactly do the “proceedings” begin? Does it begin when the police inspector submits a proposal for sanction to the government or does it begin when a person files a FIR with the police or a criminal complaint with the Magistrate requesting him to order an investigation? In either case, how exactly is a journalist who is already reporting on the alleged offence by the public servant supposed to be informed that the embargo on reporting has been initiated? What happens if there is a PIL pending in a High Court or the Supreme Court?

None of the above questions have simple or clear answers from a reading of the provision. Such vagueness in drafting a law, can be a ground to strike down a law after the Supreme Court judgment in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India.

The second pertinent question that should be asked of the Rajasthan Government is how exactly does the Rajasthan Police expect to enforce such a provision of law in cases where the national media or social media users are resident outside the jurisdiction of the State of Rajasthan but whose speech is available within the State? These proposed amendments apply only to those residing within the State of Rajasthan and should not apply to residents of other states. However criminal law is not so simple in the age of broadcasting and the internet where content is simultaneously published or broadcast across the country in an instant. What happens if someone broadcasts or makes available information over the internet to residents of Rajasthan in violation of the proposed law, can they be held liable for committing an offence within the State of Rajasthan and thus prosecuted? I am not sure of the answer.

Does this law violate the fundamental right to free speech?

Several legal experts have condemned this proposed Rajasthani legislation and have predicted that it will be struck down for violating the fundamental right to free speech in Article 19(1)(a) especially the bar against prior restraint of free speech. I am not so confident about such an outcome given some of the Supreme Court’s free speech jurisprudence in the recent years.

Two judgments are of particular concern.

The first is the judgment in the case of Sahara India v. SEBI where a 5-judge bench whipped up a new doctrine of postponement of free speech where although speech could not be barred, the court could effectively push the date on which such speech could be made to the public. The logic for postponing such free speech, in the court’s opinion, was to protect the right of the accused to a fair trial. It located this power under its constitutional power to punish for contempt, reasoning that such orders were required to ensure the administration of justice. The relevant ratio of the case is as extracted below:

The constitutional protection in Article 21 which protects the rights of the person for a fair trial is, in law, a valid restriction operating on the right to free speech under Article 19(1)(a), by virtue of force of it being a constitutional provision. Given that the postponement orders curtail the freedom of expression of third parties, such orders have to be passed only in cases in which there is real and substantial risk of prejudice to fairness of the trial or to the proper administration of justice which in the words of Justice Cardozo is “the end and purpose of all laws”. However, such orders of postponement should be ordered for a limited duration and without disturbing the content of the publication. They should be passed only when necessary to prevent real and substantial risk to the fairness of the trial (court proceedings), if reasonable alternative methods or measures such as change of venue or postponement of trial will not prevent the said risk and when the salutary effects of such orders outweigh the deleterious effects to the free expression of those affected by the prior restraint. The order of postponement will only be appropriate in cases where the balancing test otherwise favours non-publication for a limited period.

Although this interpretation was meant to apply to criminal trials, there have been cases, like the infamous gag order in the Swatanter Kumar case where the Delhi High Court invoked the Supreme Court’s reasoning in the Sahara case to impose curbs on reporting even when a formal criminal complaint was not filed against Justice Swatanter Kumar. It does not take much to extrapolate this reasoning to the ‘gag’ provisions in the Rajasthan Ordinance. The Rajasthan Government can argue that the gag order, which is limited to within six months of receiving the request for sanction to investigate, is required to protect the right of a public servant to receive a fair trial. Thus, like in the Sahara case, the Rajasthan Government can ask the court to balance the fundamental right to free speech with the fundamental right to a fair trial under Article 21 of the Constitution.

The second case of some concern is the judgment by Justice Dipak Misra of the Supreme Court in the case of Subramaniam Swamy & Others v. Union of India where the court, on the basis of some rather tenuous logic, declared ‘reputation’ to be a fundamental right. This was the case where the court dismissed the challenges against Section 499 of the IPC which penalizes defamation with criminal consequences. The court used logic similar to the Sahara case to conclude that the fundamental right to reputation under Article 21 could be the basis of curbs on the fundamental right to free speech. A relevant extract of the judgment is as follows:

Right to reputation is an insegregable part of Article 21 of the Constitution. A person’s reputation is an inseparable element of an individual’s personality and it cannot be allowed to be tarnished in the name of right to freedom of speech and expression because right to free speech does not mean right to offend. Reputation of a person is neither metaphysical nor a property in terms of mundane assets but an integral part of his sublime frame and a dent in it is a rupture of a person’s dignity, negates and infringes fundamental values of citizenry right. Thus viewed, the right enshrined under Article 19(1)(a) cannot allowed to brush away the right engrafted under Article 21, but there has to be balancing of rights. (sic)

Combine the Sahara judgment logic of gag orders, with the judgment in the case of Subramaniam Swamy and it is possible to create a constitutional safety net for the gag provisions in the Ordinance promulgated by the Rajasthan government. This is not to say that such gagging of the media is desirable or in the interest of the people but to merely point out how the Supreme Court’s shaky jurisprudence has provided a foundation for the legislature to push for more restrictions on free speech.

There has been some chatter that these provisions will not withstand a constitutional challenge despite the naked attempt to co-opt the judges into the ambit of these controversial gag provisions. Again, I would not be as sanguine. The fact of the matter is that the higher judiciary has a terrible reputation of gagging the press to protect its own against not just allegations of corruption but also mere criticism. The modus operandi in these cases is for the High Courts to pass gag orders and then on appeal, by which time the controversy has died down, the Supreme Court will step in to over-rule the High Court.

One such example is the Mid-day case, which I wrote about here where the newspaper was hauled up in 2007 for contempt because it published a cartoon regarding the controversy surrounding former Chief Justice Y.K. Sabharwal. In 2017, the Supreme Court over-ruled the High Court on its finding of contempt against Mid-day. In 2003, the Karnataka High Court issued contempt notices against 56 journalists for reporting on a sex scandal involving 3 judges of the High Court. The Supreme Court on appeal issued a stay but is yet to deliver a final ruling.

In 2001, a bench of 5 judges of the Delhi High Court ordered the seizure of Wah India! magazine edited by Madhu Trehan and gagged the media from reporting about the contempt proceedings initiated against Trehan and the others. The cause for these orders? Trehan and her colleagues had dared to carry an opinion poll amongst senior advocates on their perception of the judges of the High Court. Some of the judges scored low on the perception of integrity. With judges like this is it any surprise that governments like the one in Rajasthan are proposing to gag the media in corruption cases?

The odds as of now are in favour of the State of Rajasthan.