Revisiting the mothers who protested AFSPA

BOOK REVIEW

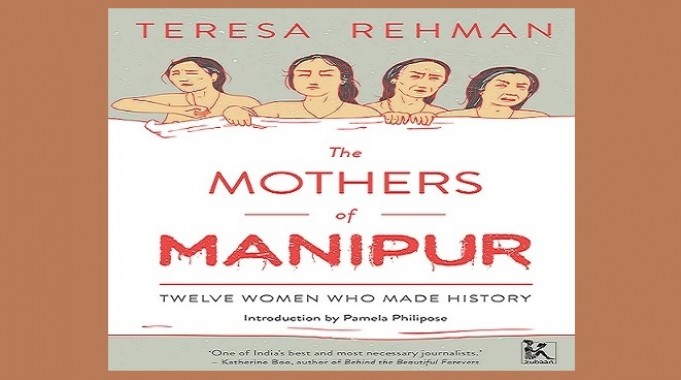

The Mothers of Manipur, by Teresa Rehman, Zubaan, New Delhi, 2017, 196 pages, price Rs 325

The Mothers of Manipur is a journey of a reporter to find the lives behind the news reports. Journalist Teresa Rehman, in her debut book, traces each one of the 12 mothers who stripped in front of the Kangla Fort in Imphal on 15th July, 2004 in protest against the rape and killing of Thangjam Manorama Devi. In finding the 12 women, Rehman also find stories of Manipur – its conflicts and its resilience. Through a number of other characters, some of them famous, The Mothers of Manipur captures the complex picture of contemporary Manipur.

Manorama’s mutilated body, ridden with bullet holes, including in her vagina, was found near her home one July morning in 2004. She had been picked up by the Indian Army the night before. A few days later, a group of mothers staged a unique protest that has been much discussed - in the context of conflict and women in India, of the battlefield that is a woman’s body and the politics of its nakedness - by activists, the media, feminists, and academia.

The bravery of these elderly women in taking off their clothes to protest against repeated sexual assaults by the armed forces has been lauded before. Pamela Philipose says in the introduction, “The images of Meira Paibis, some of them over 60 years of age, stripping outside the headquarters of the Assam rifles at the Kangla Fort in Imphal, holds a significant place in the crowded annals of contemporary India.”

Much has been written about Manipur too. As a well-known musician friend of mine from Imphal jokes: “I am writing a book on all those people who are writing books about Manipur”.

Jokes apart, The Mothers of Manipur fills a void. Rehman gives faces to those naked bodies and turns them into real women. They are little girls who grew up wanting to go to school, daughters who looked after families, wives who earned respect from their husbands or abandoned them, women who fought against injustice and for change in their societies, and friends who supported each other and sometimes failed in doing all these. They are activists, poets, actors, businesswomen.

The book is successful in capturing the lives, aspirations, despairs and failures of the Mothers of Manorama. As a feminist, I thank Rehman for this book. I think that her visits to the women and hearing their stories also gave the women a sense of pride. As Ima Ganyeshwari, one of the 12, says to Rehman: “I am surprised that you have come here. Nobody bothered to come and meet us. Nobody cared to ask why the 12 mothers of Manipur had to stage such a protest.”

The stories are varied and incredible. If one is a ‘wise shopkeeper’ selling assorted knick-knacks in Ima Keithel (Mothers’ Market), another is a dancer, an actor, and a failed wife who has left her husband and family and lives in the NGO office. They all come from varied backgrounds. A few are well off while some find it hard to make ends meet. If one is a college graduate, another has studied only till Class 1. A few have supportive families who feel proud of what their wives or mothers did while others do not enjoy such support.

“I was stunned but also proud. I wanted my mother to achieve her goal’, says Ima Ramani’s son who saw the protest on TV. On the other hand, Ima Sarojini’s husband grumbles, “I can’t tell her anything. She has overstepped the boundary.”

What is common among them is that they are all actively involved in their society through social organisations. They are the Meira Paibis, the torch bearers. ‘Meitei women are unique as they are deeply concerned about the society they live in,’ observes Rehman. What they also share collectively is bravery and determination.

And yet, on another level, they are also ordinary women. Beyond the bravery of stripping naked in public in a conservative society like Manipur, there is also fear, shame, doubt, and anxiety. They all speak about being anxious the night before the protest. Many of them faced contempt and disapproval from their families and neighbours and it is this vulnerability of theirs which makes these ordinary women extraordinarily memorable.

The book is successful on several other counts. It tells stories not just about the mothers but also about Manipur. As Teresa says, “Manipur is full of opinions, angry discussions and incredibly touching stories.” These stories capture the nuances and permutations of the conflict, of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), and of armed rebellion in everyday lives, along with extraordinary examples of resistance and resilience.

Plainly speaking, Manipur has been a mess for the past few decades. If you follow stories coming out of Manipur in recent times, it is almost impossible to imagine the idle, peaceful, sharing, community lives many of the mothers remember while narrating their lives. On the other hand, if one has been following Manipur, it is also almost impossible to miss the edgy art, music and literature that are coming out of the state.

Month-long economic blockades are countered by new innovative businesses. Inter-community conflicts and UG threats are countered by music festivals and theatres. Imphal today has a large number of people who have returned to their homeland after completing their studies and building successful careers in India and abroad. Many of them want to do something to change the situation at home. They all want peace.

Rehman follows a number of well-known names who have been pioneers, including the late, much- celebrated theatre person, Kanhailal and his wife Heisnam Sabitri. Incidentally, Kanhailal and Sabitri had staged a play, Draupadi, a few years before the Manorama protest in which Sabitristood naked in front of a soldier, daring him to look at her body. In Kanhailal’s words, “What is common between the incident and the play is that they both portray the decades-long oppression by security forces in the region.”

There is Akhu, a post-doctorate in physics who studied in Delhi University and is now a full time musician. His music talks about life in Manipur and the emotions and experiences of a young generation growing up in conflict and violence. Then there is a museum maker, a doctor from London who is working to make Manipur beautiful through his Blooming Manipur project, an HIV widow who is fighting for her rights along with other women, and a social activist who uses the traditional Meitei dress of the Phanek and Enaphi to talk about her land at international platforms. And, of course, there is Irom Chanu Sharmila.

Sadly, though, the thread that weaves all of these stories and lives together is the violence and AFSPA. All the voices in the book narrate stories of extreme violence. A mother who was sleeping with her child under the mosquito net in her bed when she was killed; the massacre at a football match where 14 people were gunned down; Irom Sharmila who fasted for 15 years; and all the people in between. Throughout it all, there is one appeal, one demand: take AFSPA away. Or, as Akhu the musician says in his song: ‘’It’s called ‘AFSPA, why don’t you go fuck yourself?’.

The only flaw is that Rehman has been subjected to some misinformation which resulted in an uproar on social media just after her book was released in Jaipur. The criticism has not been about what is written in the book, rather about whether she should write a book on Manipur. I am not going to venture into this area. My only miniscule critique of the book is on its style and craft and its journalistic nature. I will start with the second first.

Journalistic writing has its own place and limitations. The content is often premeditated and singularly sought. The Mothers of Manipur, at times, and I have to say not all the time, felt as though it was done in a typical journalistic hurry. While Teresa has been able to capture the essence of Manipur with the methodology of pre-formulated questions, it left me longing for more depth. There are often moments in the book where there are explorable crevices in the stories. They are left unexplored and the next pre-formulated part comes on. I wish she had had time for more exploration.

Two, style and craft are deeply connected to the investigation or methodology, especially in non-fiction writing. Rehman follows each mother’s story through another story of Manipur. She writes about the Ima Keithel before she lands at Ima Ibhemel’s shop. She follows the HIV widow before she proceeds to Ima Mema’s home. While some chapters flowed flawlessly in this format, in others it felt somewhat forced. If these were a series of articles you read in a magazine or newspaper this weakness would not be noticeable, but in a book format, I could not not-notice it.

Oh, and I have a third. The tone. Although journalistic in research and presentation, Rehman is gushingly eulogistic about Manipur and the women throughout the book. This leaves a saccharine-like aftertaste for, with all its glories and warriors, Manipur is just another place in this conflict-ridden world and the mothers are only human.

The book does not take a serious critical look at the issues it raises - women’s rights within Manipuri society and the Meira Paibi movement. Manipuri society is as conservative and patriarchal as it gets and the Meira Paibis are not out of that mindset either. While issues related to violence against women is objected to, young women still face extreme family restrictions while going out of the home, especially after dark. There is corruption and there is ambition amongst Manipuri people. The book kind of misses all that while pursuing the Mothers’ and Manipur’s glory.

In the end, questions still lingers in the mind. Was the protest successful in bringing any change? What happened to the dream for which the Mothers of Manipur stripped naked in front of the whole world? How do they feel about the protest after so many years?

‘After the protest, Ramani thought that this was probably the ultimate protest against the Act. But to her dismay, the state of affairs has not improved. Initially, the women had hoped that there would be some amendment to the AFSPA. …but were disappointed at how little they had achieved’, writes Rehman.

In the afterword, Manorama’s mother Khumaleima comes in. She waited four years to perform the funeral rites for Manorama whose body was cremated by the authorities as unclaimed as the family refused to accept it without a postmortem report. She does not know how long she will have to wait to see AFSPA go. “…Only when it will go I will be sure my daughter’s soul will rest in peace”.