Romila Thapar and others: averse to public debate?

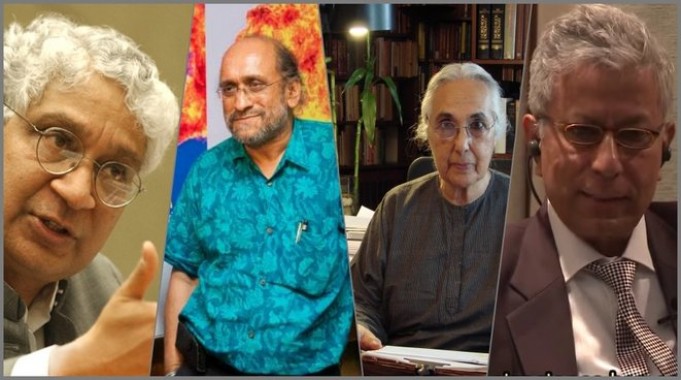

(Left to right) Deepak Nayyar, PG Thakurta, RomilaThapar, Dipankar Gupta. Pix credit: The Wire

Historian Romila Thapar’s The Public Intellectual in India, a book she and five others wrote, was much acclaimed when it was published in 2015. Thapar wrote the introduction to The Public Intellectual as also its opening chapter, To Question or Not to Question? That Is the Question.

Thapar examined this proposition in the context of the rise of religious nationalism and the lack of public debate in India. The lack isn’t because there are no public intellectuals around. She said it is because “the critical mass that is required for public debate to become essential to our civic life is not as large as it needs to be.” With that critical mass missing, those who “would like to question or comment succumb to self-censorship,” Thapar writes.

In The Public Intellectual, Thapar identifies the people who are likely to question. They are those whose breadth and depth of knowledge is formidable. But they need not be scholars. They can also be people who enjoy a professional stature that persuades people to listen to them.

Thapar’s sharp observations have now acquired an ironic tone against the backdrop of the Sameeksha Trust laying down stifling conditions for the editor of the Economic and Political Weekly (EPW), a high-brow journal it publishes. Such conditions, as is well known in the media, are almost always crafted to compel editors to resign. This is precisely what the EPW’s editor, Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, did on July 18.

Thapar is a member of the Sameeksha Trust. She is much too accomplished to not be known to readers. Google other members – Deepak Nayyar, D.N. Ghosh, Dipankar Gupta, Shyam Menon and Rajeev Bhargava – and you just might start to think that the Sameeksha Trust is India’s most formidable brain trust. They indeed fit Thapar’s bill of people most likely to question.

Yet, in the week gone by, sadly and disconcertingly, all of them appear to have contributed, willy-nilly or consciously, to the existing culture of self-censorship. By crafting a situation in which Thakurta had either the option of accepting humiliation or resigning, India’s exceptional minds have communicated to lesser mortals in the business of writing that it might not pay to question.

Anyone who wishes to question runs the risk of paying a price for it. This could be in the form of abusive trolls, of which Thapar too is a recipient; or a blowback from the government, as for instance the raids that NDTV was subjected to recently.

No less significant is the cost defamation suits threaten to impose on the writer. He or she has to engage lawyers to represent them in protracted court battles. It is expensive, time-consuming and harrowing. In case criminal defamation cases have been filed against the writer, he or she runs the risk of being jailed.

Was it the kind of price the Sameeksha Trust members might have been unwilling to pay? To answer the question, rewind to what brought the Trust and Thakurta to a head.

Thakurta and three co-writers published two stories on the EPW website disclosing that the Modi government had allegedly favoured Adani Power Limited, a business subsidiary of Adani Group. The story prompted Adani to serve a legal notice on the Sameeksha Trust, Thakurta and the other three co-writers.

Thakurta engaged a lawyer to reply to the legal notice. Both the notice and the reply to it were placed on the EPW website. The Sameeksha Trust members took umbrage to Thakurta initiating a legal process, as they said, “without informing, let alone obtaining approval of, the Trust although such a decision was not in the domain of the Editor to make.”

At a special meeting of the Trust on July 18, it was conveyed to Thakurta that “he had committed a grave impropriety amounting to a breach of trust, in taking a unilateral decision on a matter where any decision could be taken only by the Sameeksha Trust as the governing board.”

Thakurta, on his part, apologised to the Trust members for what he thought was just a procedural lapse. The Trust insisted that it was a case of grave impropriety, told him he would have to take a co-editor, and ordered him to take down the stories.

Thakurta resigned. Asking an editor to take a co-editor is one of the many ploys the privately-owned media deploy to get rid of journalists not willing to play ball.

Was Thakurta’s failure to intimate the Trust members about the legal notice a procedural lapse or grave impropriety? In The Public Intellectual, Thapar is critical of the media reporting of communal riots. She writes, “The politics behind such activities have to be enquired into.” It is precisely in this spirit the Trust’s statement, and action, need to be analysed.

As such, the Sameeksha Trust should have known about the contradictions in the laws and norms governing the media. Publishers and even printers are named in defamation suits because the law holds them responsible for what is published. Yet the Press Council’s norms regard the publisher’s attempts to apply a sieve to what is published as unacceptable interference in the editor’s freedom. This creates friction and tension between the publisher and the editor. The former can be penalised for decisions the editor took alone.

This lacuna apart, it is the editor’s responsibility to decide on the editorial content. It is he who is therefore best placed to respond to rebuttals, including legal notices, as it is he who is most aware of the nuts-and-bolts of the story, so to speak.

In other words, even if Thakurta had informed the Trust about the legal notice, the responsibility and task to respond to the legal notice from Adani would have been his. The Trust members wouldn’t have had the wherewithal to rebut Adani’s legal notice. For instance, they wouldn’t have known about the documentary evidence Thakurta may have possessed to write the stories he did.

Mind you, the EPW had only been served a legal notice. A defamation suit hadn’t been filed yet. As is the norm in the media, the legal notice is promptly answered and the legal strategy is worked upon only after a defamation suit is filed. Clearly, the Sameeksha Trust had no stomach for it. They wished to evade messy court battles.

There were other options that the Sameeksha Trust failed to exercise. For one, its members could have filed a separate reply to Adani’s legal notice. But, again, their response wouldn’t have likely differed from Thakurta’s substantially, unless it is assumed that they believed the EPW’s stories on Adani didn’t pass muster. However, the statement the Trust issued after Thakurta resigned does not give us a clue to their opinion on Thakurta’s stories.

For the other, even after Thakurta resigned, the Trust didn’t have to taken down the stories perceived to have been against the government and Adani. Thakurta had anyway exited from the EPW – the price for impropriety had been extracted!

What purpose was then served to take down the stories on Adani from the website? Since the legal notice was prompted by the stories, their very disappearance from the EPW website ostensibly served Adani’s purpose of not letting readers to know about the alleged favours that the government bestowed on him. In other words, the Sameeksha Trust no longer faces the threat of having to contest a criminal defamation suit.

In the special meeting that Sameeksha Trust convened on July 18, much of the 45 minutes of discussion was spent on imagining the possible consequences of the criminal defamation suit going against them. Their worries are understandable. Who’d ever want to spend a spell in jail?

Nevertheless, the EPW controversy shows that India’s public intellectuals wish to pay a minimal price for speaking out. Thapar has been subjected to vicious attacks, but one wonders whether Dipankar Gupta, Shyam Menon and Rajeev Bhargava have undergone such verbal retributions.

The realization that public intellectuals are willing to pay only a minimal price should fill all of us with dread. As such, a large section of the media, rather mindlessly, endorses the Modi government on every issue or, alternatively, steers clear of commenting on it, neither praising nor critiquing it.

The EPW doesn’t belong to these two categories. It is in a category of its own. The Sameeksha Trust’s statement on Thakurta’s resignation said the EPW has earned its reputation as “independent, impartial journal over five decades, for publishing scholarly articles – research-based academic writing and evidence-based public policy critiques – and providing incisive analysis….”

The statement then went on to hold out the hope that there was no question of the Sameeksha Trust “bowing to external pressures of any kind. It is guided solely by the objectives of maintaining the ethos, quality and standards of EPW, while ensuring spotless propriety and ethics in the working of its staff.”

Is it an innuendo against Thakurta’s brand of investigative journalism? It is hard to tell. Yet there can be no denying that the EPW under Thakurta’s stewardship did create a buzz. It certainly emerged as an alternative site where was laid out, in great detail, the menace of crony capitalism, on which most publications do not report.

Indeed, it might be interesting to know whether the traffic to the EPW website swelled over the 15 months of Thakurtra’s editorship. Certainly, its stories on Sahara and Adani, judging from the shares on social media, will have outstripped most of the magazine’s pieces.

Obviously, the EPW was never meant to be in the game of numbers. It will now retreat to its corner where it will produce articles by the scholars and, largely, for the scholars. It is a go-to place for many journalists to do their research. The EPW should justifiably feel proud of it.

However, such articles were also published over the last 15 months, under Thakurta’s editorship. In addition, the EPW site provided stories others in the media shied away from. This emerging aspect of EPW’s personality will likely be suppressed. It will make the magazine neither mainstream nor disruptive. Politicians don’t mind ideological contestation as much as they do publishing evidence of personal corruption, of favouring one company or the other.

It is the EPW’s choice to take the corner where the studious, the scholarly and the serious too flock.

But one thing is for sure – Thapar, Gupta, Bhargava, Menon and other Trust members have forfeited their right to lecture us in the media on our shallowness and our failure to interrogate and challenge Power, of not initiating meaningful public debate, charges that The Public Intellectual makes very sharply. Not only have the Trust members been found wanting in sparking robust public debates, they have imitated the style media barons adopt in booting out editors.

(Ajaz Ashraf is a journalist in Delhi. His novel, The Hour Before Dawn, has as its backdrop the demolition of the Babri Masjid. It is available in bookstores.)