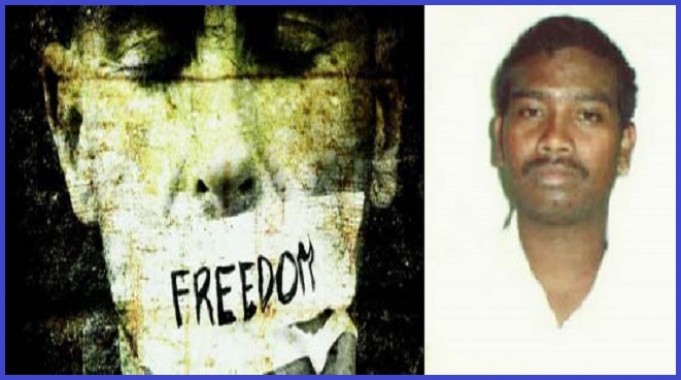

Santosh Yadav: free again, and undeterred

Chhattisgarh police will soon figure out that it simply can’t keep a good man down as journalist Santosh Yadav returns home to Darbha, in Bastar district after spending one-and-a half years in prison, full of plans to keep up with his ‘patrakarita’ and ‘samaj seva’ and tell the world about the plight of the adivasis in this strife-torn area.

Yadav was granted bail by the Supreme Court on February 27, making him the third journalist after Prabhat Singh and Deepak Jaiswal to be released on bail. While their cases will continue, adivasi journalist Somaru Nag, arrested in July 2015, was acquitted by the Chhattisgarh High Court in July 2016 due to lack of evidence against him.

Yadav was arrested on September 29, 2015, for alleged involved in an encounter during a road operation that claimed the life of a police officer. He was charged with criminal conspiracy and aiding Maoists under various sections of the Indian Penal Code, the Arms Act and the draconian the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, and Chhattisgarh Public Security Act (CPSA).

An ebullient Yadav, happy to reunited with his family, told The Hoot in a telephonic interview, that his first priority was to contact the families of people still languishing in jail and get word out on their condition. “So many youth are in jail, some of them for years. In the process, some have lost their parents, some have aged parents and there is no one to look after them. Now that I am out, I have promised them I will try and help their families”, he said.

Yadav, who expressed gratitude for the number of journalists, activists and lawyers who had extended support to him and campaigned for his release, said he never expected to be in jail for so long. But lawyers fighting for his release were aware of the highly restrictive bail provisions of the UAPA and CSPA. Indeed, advocate Shalini Gera of the Jagdalpur Legal Aid Group, had told this writer more than a year ago that there was grave apprehension that he would languish in jail despite the lack of evidence against him.

Yadav felt that the police had been after him because they felt he did ‘too much’ of reporting on adivasis and their plight. He himself was under the police radar since 2013 for getting information out on adivasis caught between the conflict between the security forces and the armed Maoists. The arrest came when Chhattisgarh Police Special Task Force Commander Mahant Singh gave a statement that he could see Yadav’s face in the light of a parabomb that was flared during an ambush in Darbha in August 2013. But, in an identification parade memo dated January 1, 2016, Singh “expressed inability to identify the accused with certainty.”

Despite this, Yadav’s bail application would simply not come up for hearing. Police had charged him, along with 18 villagers, for the crime and would never bring all 18 to court together, citing some pretext or the other, said Adv Gera.

As a local who knew the area intimately, Yadav was a vital link between the adivasis and other journalists, says journalist Malini Subramaniam, who was forced to leave Jagdalpur overnight when a local vigilante group threatened her in February 2016.

Yadav was clear that arresting him was a warning to him to remain silent and a punishment because of his critical news reportage. “The police were completely opposed to the work we did and the kind of news we used to bring out about adivasis,” he said.

“I became a journalist in 2008 as a reporter for Navbharat newspaper and then took on agency work by 2013-14. I was always interested in journalism and liked photography. I could see the huge misery and oppression that adivasis face and I felt it was wrong and that we must do something. We couldn’t keep quiet about it,” he said.

Once, he recalled, there was a brutal assault on women, men and old people in Badri village. Another colleague had first reported on the assault but it didn’t seem to make any impact. “Then I felt I must also report on this and add my voice to it, he said. Yadav received threats for these reports and warned that he would be ‘dealt with’.

“But I said I don’t care, I’ll face whatever it is. The government will try to stop you but we can’t keep quiet,’’ he said, adding that for a man who never considered silence as an option, even jail was not deterrent enough. “Jails are tough places. You don’t get decent food, there’s no medical care for inmates and if you ask for anything, they only respond by beating you. We had gone on strike in November, 2016. We had a few demands, some 14-15 demands about proper food, medical facilities etc.”

Yadav said prison officials entered into the jail and lathi-charged the protesting inmates. Some were grievously injured and Yadav himself fell unconscious and had to be admitted to hospital for treatment. He was not immediately given any treatment. “Instead, I was put into the anda cell (solitary confinement)” he said. An Amnesty International report said that Yadav was admitted to a hospital in Jagdalpur and later, transferred to a district jail in Kanker.

Yadav’s family is supportive, he said, though they do worry about him. But I keep telling them there are so many people in a worse situation than us. We should think of them, If we don’t, then what will happen to them?

Yadav is also extremely critical of the provisions of the Chhattisgarh Public Security Act (CPSA). “It is being misused totally. It never applies to people who really need to be booked under it. What is the reason for booking adivasis under this act? Are they destroying the land? Are they responsible for the loot of natural resources?” he asked.

In Bastar, he adds, the mining companies have completely destroyed the environment and the natural habitat of the adivasis. “The greatest oppression we are facing here is from the mining companies. And there’s no scrutiny of their illegal mining and grabbing of adivasi land, “ he said. “The open cast mining has destroyed adivasi villages. The government keeps saying ‘vikas, vikas’ (development) but is this actually happening? Are the villages really being developed? And for whose benefit,” Yadav asked.

Yadav is also bothered by the lack of unity amongst adivasis. “This is being taken advantage of by the police and the Maoists. There are some adivasis who get some education, they may get killed as informers and others may just run away and leave the villages. They just don’t have any future,” he rues.

“People ask me, you are not an adivasi. So why are you so bothered by what happens to them? But we have the same blood, don’t we? Shouldn’t we be concerned by what happens to them? It’s not important whether I am an adivasi or not. What is happening to them is wrong and we must speak out against it, he says emphatically.

For now, just out of jail, Yadav already has his work cut out for him. “I have a list of adivasis stuck in jail. So I shall start with contacting their families and try to help them with lawyers,” he says.

Geeta Seshu is an independent journalist in Mumbai, and consulting editor of the Hoot.