Scholars on India’s media economy

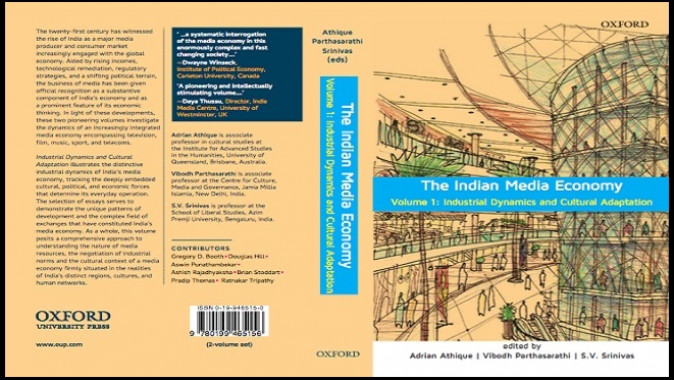

The Indian Media Economy, Edited by Adrian Athique,

Vibodh Parthasarathi & S.V. Srinivas

Vol 1: Industrial Dynamics and Cultural Adaptations

Vol 2: Market Dynamics and Social Transactions

Oxford University Press, New Delhi 2018

There is a relationship between the functioning of a modern representative democracy and the political economy of media and communication. Today when we are more likely to have experienced mediated and mediatized reality, the relationship may seem self-evident; however, to appreciate the complexity of this relationship, and hopefully address the problems, we need to delve deeper into a large body of empirical and critical scholarship on the relationship between the political economy of the media and society that often seems vexed, especially the role the media plays in advancing or hindering social justice and the fair distribution of economic resources.

Vincent Mosco, a scholar who played a pioneering role in creating the interdisciplinary field of the political economy of the media, described it as the study of power relations embedded in media production, dissemination, and consumption, especially with a focus on how value is created and unjustly appropriated in a chain of media consumption.

Robert McChesney, another pioneer in the field, has argued that the central overarching problem staring squarely at scholars of media and communication in media studies is how corporatization and the concentration of ownership in media systems is undermining democratic practices, values, norms, and allied social and political institutions. If with the growth in media systems comes diversity as well - across social difference, ideologies, and ownership - then we are likely to experience diversity of voices in the public space and consequently the deepening of democracy.

India has seen unprecedented growth in media industries in recent years, especially since the digital revolution. This growth has not gone unnoticed. Scholarly production on the political economy of the media in non-western and comparative contexts has grown as well. Yet, most theoretical and empirical scholarship on this subject has been scattered and not easily accessible to scholars and students of media studies in India. The gap has finally been addressed by Adrian Athique, Vibodh Parthasarthi and S.V. Srinivas with their two-volume book The Indian Media Economy (2018).

In these two omnibus volumes, they present innovative and new research by 17 scholars of media, journalism, and communication. Volume one is titled “Industrial Dynamics and Cultural Adaptations”, and volume two is titled “Market Dynamics and Social Transactions.”

The authors refer to their field of study as the “media economy” rather than the usual practice of calling it the “political economy of media/communication”. Although their choice of the phraseology is not explicitly explained in the book, it seems that there is a desire to largely steer clear of today’s hyper-partisan politics in the book and focus on sociological, economic, and critical-cultural analysis of media industries.

Implicit political consequences

It should not be difficult to appreciate the political consequences that are largely implicit in the studies presented in the two-volume book. Athique writes, “As a descriptive phrase, the ‘media economy’ captures the ecology of the burgeoning, complex relationships between the media sector and other social, symbolic, and financial structures. As an analytical endeavour, our stress on ‘media economy’ argues for examining not just media content but relations and systems of the circulation of mediated experiences.” P. 4.

One of the highlights of the book is how “media practices constitute social transactions” (P. 7) as a mode of economic exchange, reminding readers of George Simmel’s “triadic closure” in communication in a social network.

Many scholars would argue that in India we do not have a national media system, but an overlapping terrain of multiple sub-national media systems. Hence, a book on the Indian media is by default a research project in comparative media studies.

Not surprisingly, this book recognizes that it is a hard problem to integrate regionalized and federalized media formations under an overarching comparative framework for the Indian media economy. Athique, the lead author, makes a provocative argument, “An Indian media economy did not exist prior to the 1990s, then, because much of necessary real estate was monopolized by the government.” (P.8). Primarily because, as he argues, India never had, and will likely never have, “a fully integrated media market.” (p. 16). Yes and No. If we are looking from the demand-side then the India media was always, and will likely always be, a federalized sub-national system. Yet there was a thriving private entrepreneurship with an underlying integrated media economy in the domains of newspapers, books, music, and movies.

Supply-side perspective

From the supply-side, in substantial measure, the Indian media was already integrated into a fledgling common market by the end of the first decade of Independence. The partnership between the advertising industry, the Indian Newspaper Society, and the central government’s monopoly over making available subsidized resources such as newsprint and raw film stock sustained a fledgling Indian common market.

Dallas Smythe had argued that from a supply-side perspective in the economy, the media is in the business of delivering audiences as commodities to advertisers in what he called the “invisible triangle” of media, advertisers, and audiences.

This argument seems to be implicitly acknowledged by Parthasarathi in his essay. The historicity of economic and media liberalization, initiated in 1991, is both a moment of rupture that brought the Indian media economy in focus, and a bridge that maintains continuity with the colonial and post-colonial media economy.

This is a refreshing departure from the bulk of the earlier literature that was spawned by post-1991 economic liberalization and media liberalization. The book not only highlights the rupture, but the continuities in the social, economic, and political logics of the media economy in India as well.

The authors have divided the book into six parts that are split across the two volumes. Volume one includes sections on resources, constituted contexts, and embedding processes in the Indian media economy. The second volume includes sections on integrated commodities, labour, and spaces of media consumption. Each part is introduced with a theoretical essay that unpacks the conceptual category alluded to in the title of the part.

Vol 1: Industrial Dynamics and Cultural Adaptations

In volume 1, the part on “resource mobilization” has essays by Ashish Rajadhyaksha, Brian Stoddart, Douglas Hill, and Adrain Athique. In the contemporary digital media economy, resource mobilization includes commodification of space and time, and upending of the Smythian notion of audiences as commodities by incorporating them as resources as well, and raw materials on the supply-side in the circular chain media production. The audiences are both consumers and consumed.

Ashish Rajadhyaksha’s essay addresses the financing practices of Hindi cinema, and how until recently the capital-intensive and high-risk businesses of making films was sustained to a significant extent by shady money from the gangster underworld of Mumbai, and hawala funding routed by the diaspora from Dubai.

To grasp the changing landscape of financing of Hindi films post recognition of filmmaking as an “industry” by the government of India, Rajadhyaksha’s essay must be read along with Aswin Punathambekar’s essay on the corporatization of Bombay cinema, and the diffluent ongoing transition from traditional family-run movie manufacturing firms to professionally organized and corporatized new media industries as an integral member of the Federation of Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industries.

Stoddart”s chapter is on how IPL was a game changer in the symbiotic relationship between cricket’s popularity, the growing Indian economy and global financial networks. The essay ties in very well with the next essay on India’s telecom centre and global financing by Hill and Athique. It is also one of the few essays that present a detailed analysis of financial data on foreign direct investment and the development of the telecom sector in India.

Part II of Volume I focuses on the role played by regulation and market mechanisms in the unprecedented growth we have seen in the media and telecommunication industries. Parthasarathy in his introductory section offersa conceptual category to understand and explain regulation that is traditionally seen as “intervention-by-the-State”, to a critical and elastic concept of “Constituted Contexts”.

Regulation and market dynamics

As India transitioned from media scarcity to media abundance, he writes “…structures shaping the behavior of media firms and the dynamics of media markets are yet to attract systematic scrutiny.” Parthasarathi elaborates on the conceptual category in the chapter on regulatory policies relating to the expansion of satellite, cable, DTH, and TRAI.

The chapter shows how the Indian government strategically exercised its regulatory function through both considered interventions - by framing policies and legislating, but at times simply not doing anything and allowing questions of policy and rules to play themselves out among industry actors through the imperfect mechanism of the market.

The relationship of policy framers with each other and state institutions is important to understand the evolution of policy. The section especially highlights the role of trade associations in shaping discourses on policy and the regulation of the media industry.

How the music industry evolved

Gregory Booth’s essay on the Indian music industry traces its history, in the context of economic and cultural nationalism, from the colonial period through to the licence raj in the post-Independence period to post-1991 liberalization.

It shows how the industry moved from the dominance of a few major legacy players in the business of recorded music industry to a highly competitive industry with new disruptive players such as Super Cassettes/T-Series. The new players broke the monopolies using both legitimate and illegitimate means such as piracy of copyrighted Bollywood music.

The chapter does not elaborate on the role T-series and many other new actors played in fostering not only cultural and economic nationalism, but in regionalization of the recording music industry as well - in empowering folk idioms and achieving the hybridization of folk music with Bollywood.

Booth’s chapter is complemented by Ratnakar Tripathi’s essay on the proliferation of Haryanvi and Bhojpuri music as a cottage industry. Tripathi presents a compelling case study of regionalization of the economy of the music recording industry. He shows how the regional music industry has internalized the piracy model as part of doing business, and in looking for viability in externalities tied to popularization of a song and artist’s celebrity appeal among rural audiences.

The notion of ‘embeddedness’

The concluding part of Volume 1 is titled “Embedding Processes”. S.V. Srinivas in his introductory essay offers the conceptual category of embedding processes by drawing on Karl Polanyi’s criticism of how economic processes are abstracted from seemingly non-economic social structures embedded in the material costs and exchange value.

Processes shaped by social structures and institutions are the primary determinants of the media economy. The social structure and political contestations are embedded in all economic processes including the media processes underlying production costs, dissemination, and market returns.

Srinivas argues that in a way this phenomenon of embeddedness is a striking feature of the media economy and must be incorporated as “externalities” to understand how, despite the negative relationship between input resources and profits, many media industries such as television news and movies just keep attracting more capital to sustain financially loss-making operations.

Srinivas writes, “The politics and economics of film therefore makes a very complex picture indeed, especially when viewed against the backdrop of what now appears to be a nation-wide phenomenon: the star politician. (p. 169). Srinivas in his essay in this section shows empirically how the embeddedness of politics and social structure sustain the South Indian film industry’s capital-intensive blockbusterfilms of superstars such as Rajnikanth, Kamal Haasan, and Cheeranjeevi.

Pradip Thomas in his essay presents a fascinating study where the notion of externalities as a conceptual framework appears as a compelling category that makes the utility/application apparent. The essay is about cross-media functioning of religious broadcasting in the Indian subcontinent, and how the phenomenon of satellite television has transformed the economics of evangelism by all religions.

The essay shows how the consumer is an embedded resource and a product of the religious media economy as well. Thomas integrates the cross-national flow of religious broadcasting with the global flow of funding negotiating national regulatory regimes on capital flows. The underlying economic model of religious broadcasting has been imported from the model of televangelism in America. However, the use of television by religious groups to spread their faith has been localized, and used by preachers of all faith groups in India.

Vol 2: Market Dynamics and Social Transactions

Volume 2 of the book, like Volume 1, is divided into three parts under the following conceptual categories: integrated commodities, labour conditionalities, and space of consumption. It has essays by Shishir Jha, Niraj Mankad, Sathya Prakash Elavarthi, Lawrence Liang, Scott Fitzgerald, Babu P. Remesh, Sunitha Chitrapu, Douglas Hill, Rashmi M, and Tania Lewis.

Introducing the conceptual category of “Integrated Commodities” Athique writes, “…our interest here necessarily lies in a broader process of commodification, through which means, modes, and outcomes of mediation are adapted for the purpose of exchange and profit.” (P. 23).

Here we see a direct link between Srinivas’s notion of how externalities of social structure and political contestation are embedded as integrated commodities in media production. The main contribution of the second volume is that it re-conceptualizes media commodities, media labour, and media industries in the context of corporatization and digitization.

The authors in the section show how corporatization and digitization of news media and entertainment media has expanded the endless process of extracting value from information and creative media products while maintaining a continuity with the core business model of delivering audiences as commodity to advertisers in a value chain.

Jha and Mankad in their essay undertake a theoretical exploration of how digital technology has in a true sense brought to the fore the integrated commodity approach to understanding the media economy and business competencies.

They show how in today’s digital processes, production and consumption are seamlessly integrated in the media economy.The integration can be seen in how, in the very early planning phase of production, and all through, the integration of different platforms of distribution and consumption is incorporated in the costs with an eye to maximizing future revenues in the value chain and expanding market share.

Andhra Jyoti – an archtype

The following essay by Elavarthi reminds us of the continuities in the embedding of externalities and integrated commodities that can be traced back to the media ecosystems of early newspapers in colonial India. Elavarthi elaborates on the notion of integrated commodities by highlighting the interlocking relationship among non-media industries on the pages of Andhra Jyoti, a pioneering Telugu newspaper in colonial India.

Andhra Jyoti did not only play a leading role in constructing a Telugu sub-national identity through the means of regional news, but also served as means of spreading national consciousness during the freedom struggle.

The main focus of the essay is on unpacking the interlocking relationship Andhra Jyoti had with Amrutanjan, a company in the business of traditional Ayurvedic and herbal medicines. The two companies evolved a model to underwrite costs and jointly reap profits for their separate enterprises.

Andhra Jyoti’s innovations in advertising, marketing and distribution likely served as a model for many successful vernacular newspapers all across India, especially Hindi newspapers in the North. Today, we see parallels of the media ecosystem represented by Amrutanjan and Andhra Jyoti in a similar interlocking relationship between Patanjali Ayurveda of Baba Ramdev and the Hindi-language media in northern India.

Copyright in cinema

Liang in his essay on ‘film as a commodity” traces the changing legal regimes of copyrights and property rights of film as a physical commodity and cinema narrative as the immaterial commodity that is tied to transferability associated with distribution, exhibition, and reproduction.

The copyright regimes that served so well in the era of physical film was disrupted by new electronic and digital technologies such as VCR, VCDs, DVD, and now digital distribution. Liang argues that the film distributed on tapes and DVD, and more likely today on as digital streaming service, have spawned claims of new rights that seem have undermined the spatial-temporal security that was associated with film as physical commodity.

The very idea of stealing of film (piracy) that was criminalized by the copyright law, needs an imaginative rethinking to overcome the challenge posed by the primacy that narrative, as the immaterial commodity, now has in the digital era. He suggests that piracy was not the same as stealing a physical film or making illegal copies of a film. In the context of his exclusive focus on piracy of movies in Asia, Liang calls for a reexamination of the legal regimes of copyright and critically evaluates past discourses on piracy and property rights in the domain of media production.

Workers in the media

Perhaps the most refreshingly valuable contribution of this book is in the attention it draws of the scholarly community to media labour. In discussing the concept “labour conditionalities”, Parthasarathi argues that work and labour in the media are perhaps the most neglected area of scholarship in the field of media economy.

New enclaves of media work and labour in television and the IT/BPO sector have de-nationalized labour and media work processes and, moreover, growth in the vernacular and regional media has led to what the book describes as de-metropolisation. These changes have come with flexible definitions of what constitutes media work and what is the value of the collective strength of workers.

The changes have fundamentally altered the industrial relation between capital and labour, which is reflected in the drastic reduction in the unionization of media workers, especially in the news media.

Fitzgerald in his essays discusses the organization of media labour as an outcome of the tension between occupational professionalization of journalists (media workers) and professionalization of media organizations. He critically explores how the relationship has been changing with corporatization, or Murdochization, of news media organizations, its routines and values.

In a way, he suggests that because of corporatization, media logic is being subsumed by the commercial logic that drives much of the media economy outside the specialized domain of news media. The intense market competition is not only over advertising revenues but over political influence.

As Srinivas and others have argued in this volume, and many others have argued elsewhere, externalities of politics are embedded as a significant factor in media logic. The resistance from journalists to corporatization and political influence comes from their desire to maintain an occupational identity and ideology rooted in education, training, and socialization on the job. However, Fitzgerald suggests that the journalistic desire to maintain occupational identity does not seem to be working in the face of intense pressure from “managerial coercion.”

The decline in the power of national level journalists’ associations such as IFWJ and NUJI and the splits within these associations have further diminished the capacities of journalists to resist changes that have been undermining the professional identity of news media organizations.

Fitzgerald concludes his essay with a case study of The Hindu. While most newspapers in India were seeing a decline in journalists who were covered by the Wage Board guidelines, The Hindu had initially bucked the trend. However, the squabble in the family that owns the paper and quick changes in editorial leadership and management, damaged occupational professional identity and reporting norms in the face of pressure to corporatize to meet the competition in a market in which The Hindu was the dominant player.

It seemed that in the tension between media logic and commercial logic, the latter came out as a winner even at the last major newspaper that had until recently resisted Murdochization.

Remesh in his essay asks why there is a “conspicuous silence on the issues pertaining to work and working conditions of journalists themselves.”Do working conditions, pay, and job security affect the quality of reporting? Most likely it undermines individual reporter’s freedom to pursue different types of stories.

The Wage Boards fade

The concluding essay in this section on media labour is by Chitrapu. She addresses declining the membership, status and power of unions and associations in the movies and entertainment television. Although among creative artists, freelancing and contracting has been prevalent in entertainment media since the early days of cinema, the crew that does much of the heavy lifting has relied on unions to protect salaries and job security. It highlights how the influence of corporatization is similar when it comes to job security and pay in television and movies.

Remesh draws his conclusions from interviews that he had conducted with about 80 journalists working in newspapers and news television. The essay starts by tracing the history of Wage Boards that were constituted under the provisions of Working Journalists Act 1956. The act regulates fair salaries for journalists, retirement and other benefits, and offers protection from being fired without just cause.

Remesh painstakingly shows how in the last couple of decades Wage Board protections have withered away across India. In major newspapers such as The Times of India, The Hindustan Times, and Indian Express, a very small percentage of journalists are covered by the 6th Wage Board awards, and most likely very soon we will have no journalists covered by the Wage Board. It is unlikely the Wage Board mechanism will survive.

It is not only the stiff resistance from media organizations to the implementation of the 6th Wage Board that undermining the protections. There are other reasons behind the withering of job security in Indian news media. Senior journalists covered by the Wage Board are retiring every day, thereby diminishing their voice in newsrooms. Additionally, media organizations have succeeded in persuading many remaining seniors in the newsroom to give up the Wage Board pay and accept attractive packages under new contracts that are negotiated individually.

The voice of senior journalists in the newsroom, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with their peers, was important when it came to protecting decent salaries and job security for juniors and new entrants into the profession.

However, the media companies succeeded in making prominent journalists see themselves as celebrities and therefore deserving special treatment compared to the rank and file. The phenomenon of celebrity journalist has almost taken over the news work of studio based television production. Almost all the new journalists today are being hired under a contract mechanism in metros, and in small towns most journalists are being hired under stringer arrangements.

There is some fundamental injustice when a few journalists make a lot of money crafting a celebrity aura supported by a massive social media following while the overwhelming majority do the grunt work of newsgathering on the streets and crowded neighborhoods of metros, small towns, and remote villages.

New patterns of consumption – the multiplex

The concluding section of Volume 2 is titled “Spaces of Consumption”. Media consumption, like media labour, is an under-researched area, and this section draws much-needed attention to this area. Athique, introducing the section writes, “Consumption is the point at which the act of exchange becomes meaningful and, thus, cultural…From this perspective, it becomes less than useful to ask whether acts of consumption are primarily culturally or economically ‘determined’, since the social nature of the transaction makes it impossible to maintain a meaningful distinction between the two.” (P.176).

Athique and Hill in their essay on multiplexes as new spaces of media consumption argue that multiplexes are disaggregating the Indian consumer of films from the masses by slicing and dicing the aggregate into classes and tastes. It has surely benefitted the production of non-mass market films that are being produced for an educated class in metropolitan India.

They suggest that multiplexes offer a movie going experience that is “socially-exclusive” from what most Indians experience. Multiplexes are “…economically significant primarily because of their capacity to commoditize personal space for a clientele living in some of the world’s most crowded urban space.” (P. 179).

Unlike in the past when it was highly likely that Indians of all classes would have seen a major film and experienced a social transaction that comes with consuming media, today multiplexes are fostering social transactions that can be curated according to social difference in society.

Rashmi M takes this idea of commoditized personal space and applies it in the domain of mobile media consumption and how mobile phones have given an opportunity to the working classes to personalize their space of consumption, which is strikingly different (and perhaps empowering), from the experience of collectively consuming in the shared space of a movie theatre or communal television watching.

The consumption of media in the personalized space of mobile phones has fostered a new type of vendor operating through kiosks and small shops trading in media content alongside providing the usual telecom services to those who do not have access to the Internet. This study merits a revisit in the context of the recent explosion of digital access through free Google Internet services in public spaces and cheap data plans precipitated by the Jio phenomenon.

New ‘telemodernities’

Lewis’s final essay for the book is on how the consumption of lifestyle, fine food, and cuisine-based programming on Indian television has been fostering “telemodernities” that are aspirational and at the same time cultivating a neoliberal individualism in familial and domestic spaces of media consumption in the context of television watching within families in metropolitan India.

As these lifestyle and food shows are inspired by similar shows in the West, they carry with them neoliberal, global and cosmopolitan ideologies of selfhood but nonetheless do incorporate a local flavour and idiom that suggests that what we are seeing is the making of glocalized telemodernities that not only are Indianized but regionalized as well.

The aspirational aspect of glocalized telemodernities is especially fascinating as less than 10 percent of Indians who fall in the middle classes can afford the lifestyles they see on these television shows. Will it foster “a liberalizing consumer middle class”, at the cost of regional diversity, or we will see making of multiple shades of liberalizing consumer classes?

Athique, Parthasarthi, and Srinivas have done an excellent job in bringing together research on the media economy by a diverse selection of scholars, and I would strongly recommend that the book finds a place on book shelves of media scholars in India and in university libraries.

Finally, without in any way undermining the contribution made by above mentioned authors who have contributed their empirical work for the two volumes, I would once again like to draw readers’ attention to the theoretical essays - preceding each part, and mentioned above - that are perhaps the most significant contribution of this book to the study of the political economy of the media and communication in general.

The essays not only introduce the empirical-grounded studies to the readers, but make an attempt to integrate the essays with overarching socio-cultural theoretical frameworks and conceptual categories, rather than engage in a mere “mechanistic accounting”, to use the phrase of one of the authors. I must also point out that in some cases the dense theoretical essays stand alone, and the reader may find it difficult to see how the introductory essays serve as affordances to navigate through the chapters that chip away at the political economy of the Indian media from varying perspectives.

Anup Kumar teaches in the School of Communication, Cleveland State University.