The India Today of the working class

For over two decades, Saras Salil has decidedly catered to the newly literates.

As ABHISHEK CHOUDHARY relates its fascinating story he finds that while the magazine~s sales are down, it continues to be popular. (Photo: Paresh Nath)

What do the working-class men and women—the artisan, the craftsman, the migrant labourer—read to learn about the world beyond their limited milieu and to momentarily forget the daily grind? Some of them in the Hindi heartland read Saras Salil, a magazine which for 22 years has offered them content customised to their tastes and interests, something that informs, entertains, amuses and tickles.

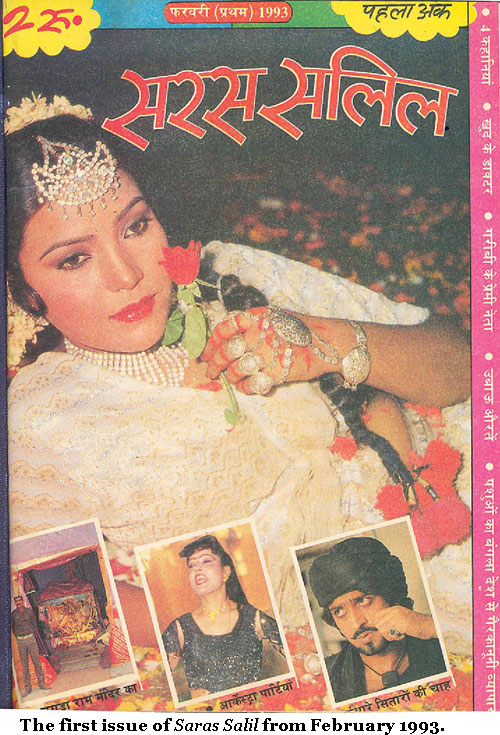

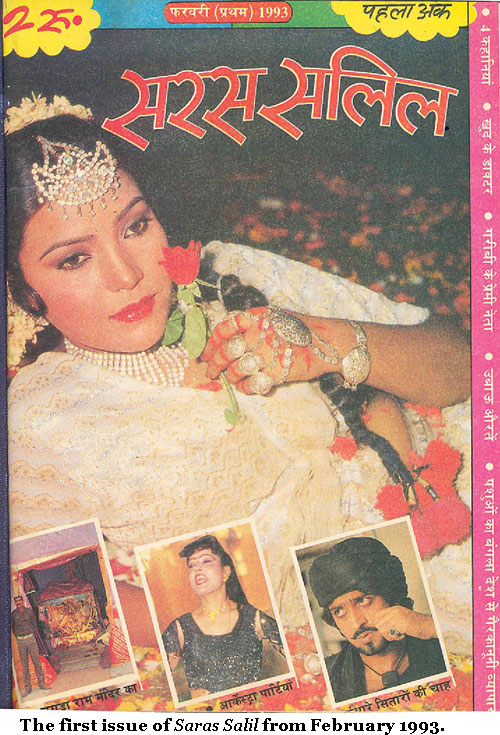

The notion of a magazine aiming to uplift the consciousness of the working class seems redolent of 19th century industrial Britain. But why not? Launched in 1993, the fortnightly Saras Salil, at its peak, was India’s highest-selling magazine in any language, selling between 14 and 15 lakh copies, with content and language tailored to appeal to the newly literates. Over the past few years, its circulation and readership have declined, but its story is that of a unique publishing phenomenon that has been so successful in achieving its purpose that it has—making its readers outgrow their need for such a magazine—negated its own raison d’etre.

India in the early 1990s had a large number of newly literates, living from day to day, who didn’t have any publication designed especially for them. This class wasn’t particularly interested in politics and economics, or social and even religious problems: “They were interested in survival,” says Paresh Nath, the owner of Delhi Press which publishes Saras Salil, and who also edits it, along with most of the publishing house's other magazines. “Our upper-caste middle class, the educated ones (in this country the upper caste and the upper class are almost synonymous) didn't bother about the ones at the bottom for centuries. But now, because of certain reasons, they were coming into the mainstream: I wanted to give them something to read.”

“Not everyone who gets an education becomes a babu,” the first issue of the magazine in February 1993 pointed out. “But education can make you a better labourer, a better artisan, a better craftsman.” The magazine was planned accordingly: “It was a little spicy. We received a lot of hate mails initially. But it was a heavy quinine: almost 30 to 40 percent content was very-very serious, and the rest was very-very light,” says Nath.

Initially priced at two rupees, Saras Salil had sections devoted to Rajneeti (politics), Samaaj (society), Budai (evil), Andhvishwas (superstition), and sex. “That segment of people doesn’t know who to talk to on sex-related matters,” says graphic manager Bhanu Prakash Rana, who’s been associated with the magazine since its inception. “Pornography is available everywhere these days, but it only titillates, doesn’t educate.”

Every issue also had fiction, a photo-feature and the last few pages were devoted to films. Special care was taken to ensure that the language was simple enough for the aam janta: “We would spend more time correcting the text than it took the writer to write it,” Rana says. “For example we would use the word mazaak instead of vyang, aurat instead of mahila, gharwaali instead of patni. The aim was that no one should have to look for a dictionary while reading it.”

The magazine struck a chord in the Hindi heartland. All of the 50,000 copies of the first issue were sold. In the next 15 months the circulation rose to 5.2 lakh. Though the magazine now sells only eight lakh copies, the fall doesn’t dismay Nath because it merely shows that Saras Salil achieved what it set out to do: “Sometimes, when I inquire why Saras Salil's circulation is not growing, I am told, ‘Sir, the kind of people you wanted to reach out to have already improved their lives, because of your magazine. Because they started reading, they understood the issues it covered, and now they are better-off so they don’t read. Your purpose has been served.”

In the recent years, Delhi Press has become popular for publishing the long-form journalism magazine The Caravan. It also publishes almost three dozen other magazines, the more popular of which are Grihshobha, Sarita and Woman’s Era (all three meant for women) and Champak and Suman Saurabh for children and teenagers respectively.

Saras Salil, at the low-priced end of the Delhi Press stable, decidedly caters to the section at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder. In fact the magazine, along with its fellow stable-mates, subsidises the prestigious Caravan which has yet to break even after five years.

Why the decline in sales?

“Because we increased the cover price,” Nath says matter-of-factly. “It used to be two rupees and poorly printed. Now it is 10 rupees and much better printed. While the price and quality improvements are fair, quite a large number of our readers could not afford it.”

He agrees that most things have gone up in price since 1993. “But you see, the chai-sellers could reduce the size of the cup of tea. I can’t reduce the number of pages of Saras Salil today to match the reader’s pocket. We increased the number of pages and printing quality which it didn’t deserve. At that time we thought it was a good decision. Maybe it wasn’t.”

The spread of daily newspapers in the Hindi belt also proved unlucky for Saras Salil. “In 1993 there was no other reading material. Now they have something else to read as well, something which gets more easily delivered,” says Nath.

Delivery, everyone at the publishing house points out, is the key problem. “Earlier people used to go to the stall to buy the magazine. These days everyone expects the magazine to be delivered at their doorsteps, and we are not able to do that,” Rana says. “There has also been a decline in the number of passenger trains,” quips Akshay Kulshrestha, who proof-reads and edits the magazine. “The express trains stop only at big stations, so the magazine can’t reach the smaller towns, otherwise the expenditure incurred on sending [per] magazine would be more than the cost of the magazine. The Railway Mail Service is available only on bigger stations. They first reach the big cities, and by the time the magazine reaches smaller towns and villages, it’s too late…”

The general price-rise in India might also have affected sales in other ways, Rana says. “The margin for the retailers has decreased, so they pay less attention to it now than they earlier used to. Sometimes they sell the promotional material that we give out for free, separately.”

Delhi Press dropped out of the Audit Bureau of Circulations survey, which measures the circulation of newspapers and magazines across different languages in the country, a few years ago, citing differences over the methodology, but the Indian Readership Survey (IRS) captures the decline in Saras Salil's readership over the last few years: from an average issue readership of 30 lakh in the IRS 2008 R2, it came down to 25.4 lakh in IRS 2009 R1. By IRS 2012 Q2 the average issue readership had plummeted to 15.5 lakh; for the next quarter, IRS 2012 Q3, the figure was further down at 13.5 lakh. The last available figure, the average issue readership for IRS 2013, was a meagre 11.6 lakh.

The magazine crisis

Magazines as a genre are in decline. In his J. S. Verma Memorial Lecture last fortnight on the state of the media, Information and Broadcasting Minister Arun Jaitley pointed this out when he said, “Magazine journalism is facing the most severe challenge. Some of the best-known magazines in the world have closed down and gone digital.”

Nath does not, however, subscribe to the view that magazines are heading for extinction. “The printed word is going to be there, it is continuing to be consumed by the same number of absolute people who were consuming it in, say, the ‘60s and ‘70s. But a very large number of new consumers avail the content through some other medium. So when you compare the readers on mobile or computer you say, oh, your percentage has gone down. But look at the absolute number, perhaps it has not gone down,” says Nath.

Saras Salil doesn’t have a website. “We found out that whichever publication has a website, people access it only if it’s free. If it’s to be paid for, people stop reading. Then what’s the point? If you have to charge them, give them a printed version, they can read it more comfortably. All said and done, with the mobile—now we have shifted from computer to mobile which is a good thing for the printed word (because the size of the page has got smaller), as soon as the phone comes, your page is gone. You can’t read a novel on a mobile.”

The analogy he likes to use is imported fast food and five star hotels. For a while, "when pizzas and burgers came, people thought the samosa will go away. But now you see every five-star joint selling a samosa. It has come back, because it has a peculiar taste for a particular class of people. This perhaps has happened all over the world. The new recipes which came and dominated for some time are competing with the native ones. Magazines, similarly, will continue to sell. Yes, magazine publishers will have to change themselves. It seems they are not ready to do that. And when I say magazine publishers, I don’t mean Indian magazine publishers, I mean magazine publishers worldwide."

It’s not as though Saras Salil isn’t changing at all. It recently started a section called Sachchi Salaah, Genuine Advice, in which readers are given a helpline number on which they call or SMS their personal problems. Bypassing the distribution muddle, Sachchi Salaah, graphic manager Rana believes, is helping the magazine connect better with its far-flung readers.

During the interview, Rana kept checking a Blackberry, given to him exactly for this purpose; every day he receives anywhere between 50 and 100 SMSs and more number of calls (sometimes at mid-nights), many from women. Rana shortlists them and selects the most representative ones to be answered by an expert. “These are things that they can’t discuss with anyone at home or elsewhere. Relationship issues: a man and a woman are friends and want to get married, but can’t, due to caste or class or any other differences. Dissatisfactory sex life: people who watch pornography can’t believe why they can’t last longer in bed than those in the films. And neem-hakims are, as you know, mostly unreliable.”

Subsidising The Caravan

Despite the decline Saras Salil currently sells a hefty number—almost 8 lakh copies—according to Anand Vardhan, who looks after Delhi Press’s advertising. A major chunk of the sales are in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, almost 3 to 3.5 lakhs each. In terms of total sales, Grihshobha comes a distant second at 3.1 to 3.2 lakh.

For the first ten years, Saras Salil didn’t get much advertising. But slowly the advertisers realized the reach of the magazine and the advertising rates improved. Grihshobha fares better in ad rates, though: “The rate for Grihshobha's premium portion (the three cover pages) is 3.5 to 4 lakh rupees, the other full-page ads cost 1.8 to 2.5 lakh rupees,” Vardhan says. “The rates for three cover pages of Saras Salil are 2.5 to 3 lakh, the other full-page ads cost 1.5 to 2 lakh rupees.”

Where does The Caravan fit into all this? “Every publishing house has something in which it wants to show off its calibre. Every hotel has a presidential suite. That suite is never hired, it is generally lying vacant. But they spend a huge amount of money on it. So it is not a paying proposition to have a presidential suite. But you have to have it. If you are a good five-star property, you have to have it, whether it makes money or not. Caravan is something like that.”

Nath admits to surprise at the fact that The Caravan, despite its acceptability, hasn't broken-even. The company can fortunately afford to subsidise it. “You must see that we have one editor for all magazines, you save lot of money in that. You have one common infrastructure. These are the things that generate economies of scale. Both Saras Salil and Caravan serve their own purposes. And for me both are important. Caravan serves one kind of audience, Saras Salil serves another kind of audience.”

But then why did he choose a slightly complicated name for a commoners' magazine? Nath chuckles at the mundane explanation he is going to offer. The Registrar of the Newspaper of India apparently was not giving names. Nath kept suggesting fancy names, and the RNI kept rejecting, saying those names had already been taken. Finally Nath was asked to pick two names. “I deliberately picked up two names which didn’t make any sense. Saras is something which is full of juice, and Salil means water. Saras Salil means water which is full of juice. It makes no sense, it really makes no sense,” he concludes with a hearty laugh.

(Abhishek Choudhary is with The Hoot. He tweets @cyabhishek.)

Such articles are only possible because of your support. Help the Hoot. The Hoot is an independent initiative of the Media Foundation and requires funds for independent media monitoring. Please support us. Every rupee helps.