The media’s rockstar humanitarian

The world’s media were in attendance at St Peter’s Square in Rome on Sunday when Pope Francis conferred sainthood on Mother Teresa, henceforth to be known as St Teresa of Calcutta. Most Indian television channels broadcast the event live. It was a big day for India, and for Kolkata especially, where she had spent almost her entire life serving the dying and the destitute. She had been a living saint, the TV channels intoned, as they interviewed joyous Indians waving the tri-colour in the hard light of the Italian sun. The media had been calling her a “saint” for nearly 50 years. The canonisation was simply the formal, ecclesiastical recognition of her status in the popular imagination.

When Mother Teresa died in Kolkata on September 5 1997, her funeral too was a massive media event, broadcast live across the world. She was a rockstar humanitarian who trotted the globe in her iconic blue-bordered saree; she was the “Saint of the Gutter”, a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, a friend of Pope John Paul II, welcomed by heads of state and photographed with celebrities around the world; and she had built up the Missionaries of Charity, the order she founded in 1950, into a formidable congregation, which, at the time of her death, spanned 120 countries and consisted of more than 3000 nuns. Little wonder that the media celebrated her in life as in death and was doing the same now that The Vatican had immortalised her as a saint.

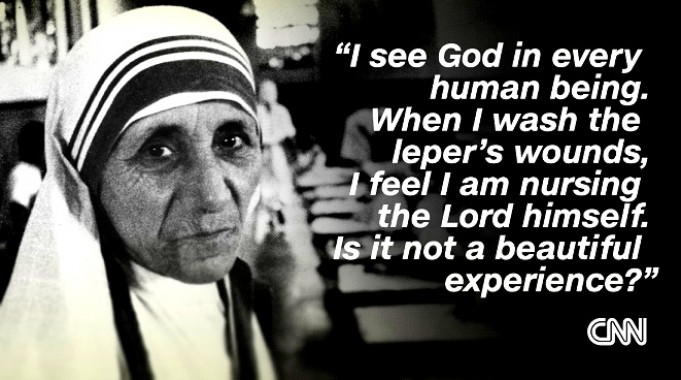

In truth, the mystique of Mother Teresa has much to do with the way the media presented her. The story of a diminutive nun from Albania who gave succour to the poor and the abandoned in a benighted Third World city was a powerful one. And once the international press had got hold of it, her renown as a divine symbol of piety and mercy was more or less assured. Those images of hers— cradling an emaciated, vacant-eyed child scooped up from the streets of Calcutta or her head bowed in humility and supplication — were beamed around the world. She got the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979. Besides the Pope, there was no bigger celebrity in the Catholic Church while she was alive.

That said, her work and legacy have also been severely questioned, the halo around her constantly challenged by allegations of the primitive facilities at her care homes, her closeness to dictators and billionaire scamsters, and her use of poverty as a vehicle to further the agenda of the Catholic Church. The same media that eulogised her extravagantly have also given play to the many criticisms against her, making her the irresistible yet controversial figure that she was. On September 3, amidst all the ecstatic coverage of India’s soon-to-be saint, The Economic Times published a scathing indictment of Mother Teresa by Aroup Chatterjee, a UK-based doctor who has long been her critic.

Mother Teresa’s ascension to global fame began with a 1969 BBC documentary on her life and work made by British journalist and commentator Malcolm Muggeridge. She had been ministering to the wretched of Calcutta for years — Nirmal Hriday, her home for the dying had been set up in 1952. But Something Beautiful for God made her saintliness — her selfless love for the poor — manifest. Muggeridge called her work “a shining light” and, in fact, was so overcome by his interaction with her that he subsequently converted to Catholicism.

Muggeridge also set in motion the idea of Mother Teresa, the miracle. The crew had shot the scenes in the poorly-lit interiors of Nirmal Hriday with a new, untested Kodak film stock. There was some apprehension that the shots would not come out well. Surprisingly, they turned out fine, their every detail visible. Muggeridge immediately said that the clarity of the images was proof of a “divine light” — it was a miracle wrought by Mother Teresa. The film’s cameraman, Ian McMillan describes the incident in a 1994 documentary called Hell’s Angel made by Anglo-American journalist and writer Christopher Hitchens and British television presenter and journalist Tariq Ali. And so, says Hitchens, this “profane marriage between tawdry media hype and medieval superstition gave birth to an icon.”

Hitchens, who died in 2011, was one of the most persistent voices of dissent amidst the avalanche of hagiography around Mother Teresa. In 1995 he followed up Hell’s Angel with a pamphlet called Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice, where he further amplified his thesis that the saintliness of Mother Teresa was seriously suspect. He pointed out that she celebrated suffering instead of trying to alleviate it, and that despite the tens of thousands of dollars she received as donations, the poor she served received almost no benefits of modern healthcare. Moreover, she seemed to have no qualms about hobnobbing with dictators like Haiti’s “Baby Doc” Duvalier or taking $1.25 million from American tycoon Charles Keating, who was later convicted in a savings and loans scandal.

Hitchens says that rather than asceticism, her institutions are characterised by "austerity, rigidity, harshness and confusion" because "when the requirements of dogma clash with the needs of the poor, it is the latter which give way.” He quotes some volunteers as saying that the dying were often baptised. Indeed, Hindu nationalist groups such as the RSS have been increasingly vocal about the charge against Mother Teresa that her humanitarian work was underpinned by a proselytising agenda.

Hitchens went so far as to call Mother Teresa a “fanatic, a fundamentalist and a fraud”, asserting that her opposition to divorce, contraception and abortion reflected the hardline, right-wing views of the Catholic Church. In her Nobel acceptance speech in 1979, Mother Teresa did make the astounding statement that abortion was the “greatest destroyer of peace today”.

But it was not just Hitchens. In 1994 British medical journal Lancet came out with a report on Mother Teresa’s hospices that revealed their rough and ready ways. Doctors and painkillers were in short supply and hypodermic needles were washed and reused, said the report. What’s more, no effort was made to distinguish the incurable from those who could be cured if only they got proper treatment. (In 2007, visiting Nirmal Hriday and Shishu Bhavan to do a story on the occasion of the 10th death anniversary of Mother Teresa, this correspondent was shocked to find the abysmal quality of care that was still being meted out to the sick and the dying and to those unfortunate foundlings, many of whom were severely handicapped.)

Again, a study published by Canadian researchers Serge Larivee, Genevieve Chenard and Carole Senechal in 2013, which analysed a huge body of published writings about Mother Teresa, said that her beatification by The Vatican in 2003 had not taken into account “her rather dubious way of caring for the sick, her questionable political contacts, her suspicious management of the enormous sums of money she received, and her overly dogmatic views regarding ... abortion, contraception, and divorce.”

The researchers went on to conclude that her hallowed image, "which does not stand up to analysis of the facts, was constructed, and that her beatification was orchestrated by an effective media campaign”.

However, such studies made little difference to the cult of Mother Teresa. The weight of her perceived saintliness was so great among her millions of followers that The Vatican fast-tracked the process of her canonisation. The Church needed "proof" of two miracles that could be attributed to her. These -- the miraculous healing of a Santhal woman from Bengal in 1998 and that of a Brazilian man in 2008 -- were also subjected to media scrutiny, with rationalists and critics denouncing them as bogus claims. But her sanctity and miraculous powers were by now a deeply entrenched faith. It could scarcely be dented by a few attempts to debunk her myth.

The Vatican beatifies and canonises more than one saintly person a year. Few, if any, command the media glare that came the way of Mother Teresa. She may be the Catholic Church’s latest saint in heaven. But she is really the first “saint” of our mediatised, hyper-exposed times — at once glorious and flawed.

Shuma Raha is a senior journalist based in Delhi

Twitter: @ShumaRaha