When reportage illuminates

Book Review

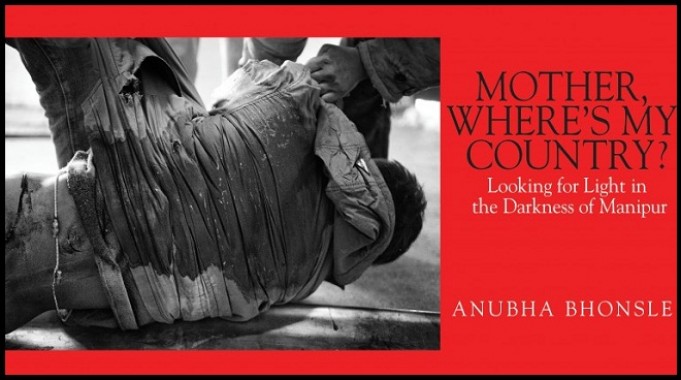

Mother, Where’s My Country by Anubha Bhonsle

Speaking Tiger, New Delhi, 2016

256 pages

In a space of a few days, three news items from the North East, a terra incognita in the national consciousness, hit the national headlines. The government imposed president’s rule in Arunachal Pradesh, while the governor accused the Congress chief minister of the state, Nabam Tuki, of contacting the Myanmar-based rebels of the National Socialist Council of Nagalim-Khaplang or NSCN (K).

The NSCN (K) is one of the factions in the six-decade long Naga insurgency that has not joined the peace framework agreement signed between the Government of India and the dominant faction of NSCN (Isak-Muivah). In the midst of the political controversy, information was leaked from the ongoing secret talks that the central government and NSCN (I-M) were closer to an agreement on autonomy for the state of Nagaland, and perhaps even a state flag for Nagaland like Jammu and Kashmir. The more contentious Naga demand to create a greater state of Nagalim (Greater Nagaland) - by incorporating Naga territories from the neighbouring states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Manipur – was, however, put on the backburner.

While India’s security establishment and strategic experts were discussing the possible implications of the likely truce with NSCN (I-M), a police head constable from Manipur came out with a confession that in 2009 he shot and killed Chungkham Sanjit Meitei, a member of Manipur People’s Liberation Army (an insurgent group fighting the government and the Naga supporters of Nagalim) on the orders of his superior. All these years, the Manipur police had claimed that it was an encounter killing.

One would expect that these high news value headlines would foster in-depth follow-up stories explaining the significance, the controversies and the insurgent groups. However, except for the story on the imposition of president’s rule in Arunachal Pradesh, which quickly became a legitimate controversy between the BJP and the Congress, the other stories soon faded from the daily coverage in the mainstream media.

My journalist colleagues acknowledge that these are difficult stories to cover. The political-economic logic underpinning coverage in the mainstream media deems that they are not important enough to go beyond snap shots – mostly because they deal with complex and entangled issues, histories, persons, and sources that do not fit into the pre-existing frames and meta-narratives of the mainstream news media.

Not surprisingly, some time back, Basharat Peer, writing in the Columbia Journalism Review, lamented that major news organizations in India were unwilling to commit resources and time to difficult stories that were best suited for the long-form, and that the best in-depth “journalism on difficult issues” appeared in the foreign press.

Without the resources and time, it is very difficult for reporters to break through the established media routines that work within the boundaries of the national capital and the heartland. The consequence of such a paucity of in-depth journalism has been that people living in the heartland have no means to better their understanding of the north east. How does one even weave a shared narrative in our national consciousness out of the occasional snap shots of the troubles in this region?

Fortunately, there are journalists like Anubha Bhonsle who find the time to work outside their daily routines to uncover genealogies and histories that tie the discrete headlines - on conflicts, atrocities, and even on humanity - that we see occasionally in the mainstream media into a narrative.

The above concerns acquired a heightened significance for me because as the headlines appeared in my news feed, I was reading Bhonsle’s Mother, Where’s My Country? on Kindle. The book’s narrative arc reminded me of The Naga Story: First Armed Struggle in India by Harish Chandola, who served as the North East correspondent of The Times of India in the 1950s. It was one of the best journalistic accounts of the insurgency.

The current ceasefire and ongoing talks with the NSCN (I-M) should give the government some confidence to withdraw the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA). The talks, most likely, may result in some durable peace because from the government’s perspective, NSCN (I-M) cadres cannot go back into the jungle, and the rebel-Naga leadership itself believes that they do not want to go back into the jungle. A surprising fact brought out in detail by the book is the ‘it’s-all-in-the-family’ aspect of the conflict, namely, how the leadership of the insurgency and the political leadership of the state administration are tied by family bonds. One brother is fighting with the insurgents and the other with the security forces.

The most refreshing part of Mother, Where’s My Country? is that, unlike many enterprising book-length reportage published in recent years, this is not reductionist in its methodology. The reporter is not out to prove a point from the get go, but to understand and explain. It adheres closely to the principles of journalistic ethnography, presents a rich description of the events and mentalities, and leaves the judging mostly to the reader.

Bhonsle’s account of the insurgency against the Indian state and the ethnic conflict among Naga, Kuki and Meitie in Manipur is primarily a human story. The narrative, anchored in stories of women raped by the security forces in Manipur and the ongoing fast by Irom Sharmila against the AFSPA, weaves overlapping heart wrenching stories with the poignancy of the six-decade long insurgency that has killed thousands.

The very opening chapters pierce your conscience and make you feel guilty for having played whatever little role you may have in normalizing the misery of people living under AFSPA and under the mafia-like criminal operation of numerous insurgent groups.

While telling this story, Bhonsle maintains a delicate balance between witnessing and recording authentic structures of feeling, what Walt Harrington once described as doing journalistic anthropology, i.e. when you “learn not to judge but record.” Describing the experience of a victim narrating her rape to a human rights group Bhonsle writes:

“Simply raising a voice would not shatter the inhuman silence at the other end, where brute power lived. And yet, pain, violation, fear had to be articulated coherently. After your name, village and the date of the incident, you had to recount the act clearly, the clearer, the better. You could leave out details of how the day started or how you were feeling that day. The act was important. The uniform, your clothes, physical features, marks and bruises, all went into the documentation. Hair pulling, being slammed on the floor, heavy hands shutting out your screams— all were documented. Vaginal wounds too. There was no place in the reports for broken nails or the buckle of a belt that dug deep into your abdomen or the fever that came from a terrible urinary tract infection that lasted for months or the oppressive smell that never left you.”

With the same level of authenticity, Bhonsle captures a very telling rambling of an Indian army officer who sees himself stuck for decades in a mind bending war with the insurgents from his own country who care little for the lives of their own people.

“But what are we really doing here? Do you know? Oh no, this AFSPA, this AFSPA that kills, trigger-happy army, trigger-happy Assam Rifles, trigger-happy everyone, except these people. You think they are not trigger-happy… I was fucking young then. It was the same shit then too. They were killing us by the hordes, then too some groups, some women, came - this one has been raped, that one has been raped, the whole world has been raped. Do you think my men will do it when they are being fired upon? I’m not saying it hasn’t happened. It has. Not one case, maybe four, maybe ten. Are you telling me that is what defines our work here, that is what defines this crap-shit we are doing here? I was young then, I am too old for this shit now. I shouldn’t even be talking to you, but you guys don’t understand.”

The writing is clear and empathetic. It may evoke different emotions in readers. It is about making us feel the pain. Does the reporter here do an excellent job of this? In my assessment, despite some shortcomings, yes. Understanding the contrast in the above two quotes is the key to understanding the reporting in this book. Writing with clarity, she helps the reader conjure up a scene, evoke an emotion and learn the story behind the snap shots we may have seen in the national headlines.

As mentioned above, one of the anchor points that hold the narrative together is the story of Irom Sharmila. Once again her story, like that of other victims, is not a utilitarian trope to condemn the Indian state but to show our heartlessness, every one of us, in responding meaningfully to Sharmila who, since 2000, has been waiting in a ward in Jawaharlal Nehru Hospital, in Imphal, for the government to tell her that she can go home and relish the taste of laphu tharo or komprek, and enjoy the company of her love like a normal young woman. Bhonsle reports:

“She is asked about love. She tilts her face, fixing her gaze somewhere near her feet, and says shyly, ‘I am a very simple girl. I will settle down, but only after my demands are met. Life is a challenge, life is an experiment.’ How does she spend her day? She pauses, a smile appears. ‘Most of the day I’m daydreaming of happiness.’”

Perhaps for the first time in all the writing on Sharmila – at least what I have read – Bhonsle helps the reader see not only the activist that she is, but an idealist didi, aunt or mother who we may have come across in our own families. There is a familiarity in the persona of Sharmila that shakes the reader right to the core. For example, Bhonsle narrates an incident from Sharmila’s childhood days, as told by her brother, Irom Singhajit, that helps us understand the unusual power in her stubbornness.

“Once, en route to school, Sharmila threw a tantrum and refused to go ahead. She sat at the foot of a banyan tree and started crying. Cajoling and scolding by elder brothers and sisters made no difference. Tired, they left her and went to school. Eight hours later, when they returned, Sharmila was still sitting there.”

Yet, to Mahatma Gandhi, this seeming naiveté in Sharmila’s stubbornness would be a compelling reflection of a reassurance in the decision that she took 15 years ago to hold on steadfast to the Truth (Satyagraha). The fast is not for Manipuri nationalism, although she has become an unwilling symbol for that too, but for the human dignity of her fellow citizens.

In her understanding of the situation, she knows that AFSPA is not only unproductive in the fight against the insurgency but is also a structural factor in causing the atrocities that are regularly committed by the security forces in Manipur and other places in the country. Surely, there must be a smarter way to deal with insurgents who shelter behind innocent civilians?

Bhonsle’s book is an attempt to present a journalistic account of facts and recollections of what happened, checked and rechecked, so that we as a nation can start working on resolving the conflicts by first agreeing on what actually happened and why it happened. This book will probably not be your canon on the north east or Manipur – there are many other authoritative accounts by social scientists – but it should be on your bookshelf as the best example of excellent, in-depth journalism coming out of India that you will read.

(Anup Kumar is the author of The Making of a Small State: Populist Social Mobilization and the Hindi Press in the Uttarakhand Movement.)