Why media players are chasing regional audiences

In the winter of 2011, Indians were dispirited to hear the news of the BBC World Service pulling the plug on its Hindi short-wave services. It was the most heartbreaking news for an audience that ranged from soldiers to Maoists and from farmers to factory workers.

The BBC, with 70 years of broadcasting in India, had become a heritage network and a household news broadcaster. Thousands of protesters began encircling Bush House in London, the then headquarters of the BBC World Service, demanding that the broadcaster overturn its decision. The controversy rocked the House of Commons. The BBC eventually won a reprieve. The Hindi service lived to see another day.

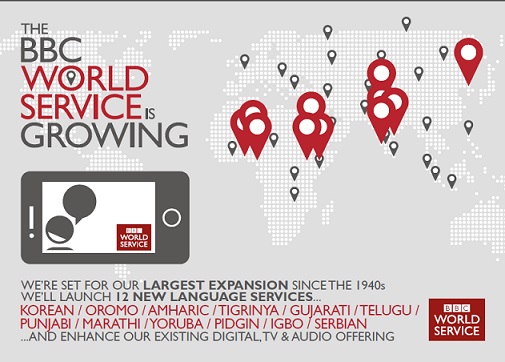

Fast forward to 2017 and the media and the internet globally are going regional, making the BBC’s proposal to ditch the Hindi service seem archaic. In fact, in October this year, the BBC took yet another huge step towards increasing its Indian language services by launching the Punjabi, Telugu, Marathi and Gujarati digital news service – a trend seen in other media outlets too who see a brighter opportunity in localizing their offering and acquiring a regional digital footprint.

The speed at which this is happening is astonishing. The web is increasingly expanding into the vernacular language space. What could be the rationale? Well, Punjabi is the 10th most spoken language in the world, as the majority of people in Pakistan also speak it. Telugu and Marathi are the world's 15th and 16th most spoken languages.

The digital space can reach 250-million Bengali speakers in India and Bangladesh. According to the People’s Linguistic Survey of India, Bengali is the second most spoken language in India followed by Telugu, Marathi, Tamil, Urdu and Gujarati. Tamil is the world's 18th most spoken language, other than being one of the official languages of Singapore and Sri Lanka.

The new imperative: go vernacular

According to the International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Engineering and Technology, 47% of people prefer reading online medium. Consequently, the potential for online media players is Brobdingnagian. The category preference in digital news across regional internet users in 2016 provides a framework for interpretation: local news and politics garnered 70%. Thus, the titans of news are planning to make – or have already done so - inroads into the lucrative regional news genre.

In 2015, The Times of India moved into the vernacular online space, operating under 'Samayam'. The Indian Express digital is all set to launch Bengali, Telugu, Tamil and Kannada, besides the existing Hindi, Marathi and Malayalam news portals.

AOL, Firstpost, Hindustan Times, The Pioneer, and The Statesman launched in Hindi and other languages and are drawing a large number of readers. India Today has been riding on the success story Living Media scripted many moons ago.

Indian language potential is barely tapped

According to a study by United Nations Population Division, Asia held sway among world internet users with 49%. India secured the second spot in Asia with a 23% share out of the 1.94 billion internet users in Asia. No prizes for guessing Asia's and the world's topper - Zhongguo took the dragon's share with 40% and 23% respectively. India ranked only behind China.

In the four billion-strong global internet population, English commands the lion’s share in digital communication. Mandarin follows with 30% and Spanish with 8%. There are a plethora of websites, pages, portals and blogs in regional languages, yet the share of each Indian vernacular language is not more than 0.01%. So that can only grow.

Traditionally, markets and rights were divided and allocated on a territorial basis. However, the strategy apparently irrelevant today to the boundaryless digital world. On the other hand, the digital footprint is increasingly becoming the product-service hybrid.

These days, the mother tongue is given much emphasis by not just newspapers and social media but every player in the digital domain. When it comes to offerings and services, the non-English speaking population need help in booking tickets, paying bills, and online shopping or trading.

Latterly, the Indian Railways has made ticket booking possible in Hindi. Recently, the Oxford University Press introduced online dictionaries in Tamil and Gujarati. Many e-commerce, retail, fintech and other industries are adding vernacular variants to their existing portals. Zerodha, an online stock trading company, launched its multi-lingual trading platform, Kite, in 2015.

Yourstory, a dedicated portal for startups and entrepreneurs, funded by Kalaari and Ratan Tata, has made its content available in 13 languages. Most of the State Governments have the user interface in local languages for better governance and utility services to suit the convenience of users. Thus, the moves on the vernacular digital chessboard are taking place at a fast pace; English is being elbowed out.

The drivers of this change are set to grow

For years, the vernacular digital space was untapped, due to low literacy rates, lack of technology, low income, and low mobile and internet penetration in India. Thus, pockets of the digitally disenfranchised persisted.

Notwithstanding the fact that English is one of the official languages of the country, a mere 15% (estimate) of Indians can read and 12% can converse in English. The rest of the Indian population is a sea of opportunity waiting to be grasped. Google estimated that the digital media would grow at 26%, with vernacular users poised to grow by 18% CAGR.

Evolving technology and the digital phenomenon, changing lifestyles, growing income levels, population and literacy rates are the key factors driving the growth. The literacy rates in rural India are increasing from 46% as per the 1991 census, to 58% in 2001 and 69% as per the 2011 census.

There are 420 million internet users in 2017. Of these, urban India commands 60% and the projected penetration growth is 9%, perhaps suggesting a level of saturation. In contrast, rural India registered 17% with a promising growth rate of 26% penetration; these numbers are a testament to the potential scope for tapping the market.

At the Digipub World conference held in September this year in Gurgaon, the websites of regional newspapers described how fast their traffic was growing.

It was mentioned that Google has produced a report which estimates that the next 500 million people coming online will be regional languages users.

So search too, is looking to be where the readers will be. There is a Hindi voice search and nine other languages are to follow. Google maps is now in four Indian languages and YouTube’s content is mostly in regional languages.

Television is doing the same thing

Television broadcasters are also on the lookout for potential acquisitions, initiating concerted efforts in a bid to attract the audience in regional territories and reviving content strategies to match the regional languages offerings by OTT and streaming players' libraries.

The broadcasting titans have significantly grown their regional audience over the last five years, either by an acquisition of the existing regional channels or through the creation of new channels.

The regional viewership share is 33 percent the total TV viewership in India. Rest of India watches Hindi and English. That's a substantial share of audience in regional demographics. In the regional pie, Tamil channels occupy the most prominent share of 25.7% in local viewership; Telugu is the second largest with 24.4%; Kannada managed 11.6%; Malayalam 9.2%; Bengali 6.6%; Marathi 4.6%; and Oriya 2.6%.

Want a sports channel in your mother tongue? Tamil viewers were wholly bowled over when Star India, last May, went a step further and launched India’s first ever regional sports channel, Star Sports1 Tamil. Star TV and Tamils are no strangers to each other. Star India took over Vijay TV in 2001 from UTV. Vijay Mallya, the beleaguered Chairman of United Breweries, was the founder of Vijay TV. Thus, Star TV knows the pulse of the Tamil audience.

The BBC nurtured a partnership with ETV and India TV for its BBC Worldview programme. Viacom18, after acquiring the ETV regional bouquet except for Telugu, baptised the channels as Colors Bangla, Colors Marathi, Colors Gujarati, Colors Oriya and Colors Kannada. Sony-BBC, a joint venture entering the Infotainment genre, grabbed a pie from the Infotainment duo Nat Geo and Discovery, to offer Sony BBC Earth in Tamil, Telugu, Hindi and English across India.

Zee is on the verge of acquiring six 9X music channels including 9X Jhakaas-Marathi and 9X Tashan-Punjabi. Sony India, arguably a laggard in the regional game, is fast catching up and planning to enter the fray with five regional entertainment channels: SAB Bangla, SAB Tamil, SAB Punjabi, SAB Marathi and SAB Telugu.

Last year, Star TV took over the Maa Telugu channel network and added Maa TV, Movies, Maa Music and Maa Gold to its chaplet. In 2010, National Geographic and Discovery Channel's initiation of separate regional feeds, albeit dubbed, proved profitable.

In 2018, the trend can only grow.

(Portions of this article have appeared in Business World earlier in December.)

Sunil Dhavala is CEO of The Third Umpire Media. He had held senior management roles at Bertelsmann, National Geographic, Fox Broadcasting, Star TV and other companies.