Community Radio: give it back to the community--III

When the Community Radio (CR) guidelines were relaxed in 2006, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (I&B) promised 4,000 new CR stations in the country. ]As of November 1, 2016, there were 200 operational stations and another 252 that had signed GOPAs (Grant of Permissions Agreements) or those who had the LoIs (Letters of Intent), spectrum allocations and I&B’s final go-ahead. Of the 1,930 applications, 1,130 were rejected, 255 were under process, 449 LoIs were issued, and 96 LoIs were cancelled.

In the previous two articles, we discussed how several stations were owned by elite groups and powerful vested interests. Some of the direct and indirect owners included politicians, government ministries and departments, and large corporate houses. Our research clearly indicates that there was a need to take another look at the guidelines, and modify them, if the I&B Ministry does intend to give CR back to specific, local communities. In this piece, we discuss possible solutions, a few recommendations, and corrective measures. We also obliquely refer to the ownership of CR stations by religious and spiritual bodies.

Who should own a CR station?

According to the experts, to begin with, there is a need to go beyond just CR and look at the entire radio segment. The reason: part of the problem is the insistence on retaining three categories of radio – public service, commercial and community. While the first two categories are well defined without ambiguities and it is clear who can own such stations, whatever remains is shoehorned into CR. So, educational institutes, government departments, commercial entities, and politicians can run CR stations, while adhering to the guidelines.

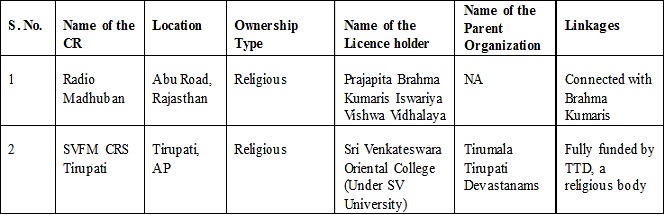

This may be an opportune time to talk about another CR ownership-related issue, i.e. the grant of licences to religious and spiritual bodies. This was an issue that was debated before the 2006 guidelines were formulated, and over the past decade. Over the years, experts charged that several religious groups got the licences even though the screening committee rejected their applications. A former member of the screening committee explained, “There are many temples, churches and other religious organizations in India running community radios under the garb of being an NGO, but all of us know that they are not.” Out of our sample of 18 stations under this study, two were owned by religious organizations.

Table 1: Religion and CR

I&B Ministry data hints that apart from such Hindu bodies, there are Christian, Islamic and Sikh organizations which own CR stations. Sajan Veniyoor, who was involved with the formulation of the 2006 CR guidelines, says: “First, we said no to religious groups. But then the argument was offered that religious groups like the Tibetans were also ethnic minorities. So, what do we do if they apply? So, we said that the religious groups may have a licence but they cannot use it for religious purposes. This was a naïve presumption. Of course, these norms are violated.”

Now we can get back to the key question posited above, who should own a CR station?An option may be to expand and broaden the categories of radio licences and include low-power radio stations in them. Thus, the above-mentioned groups can legitimately own low-power stations while CR can be restricted to local and specific communities. Arti Jaiman, who runs a CR station in Gurgaon, contends that more categories have to be created. “One needs to separate campus and farm radio (owned by Krishi Vigyan Kendras and State Agricultural Universities) from CR licences. Then this sham of CR is taken away from campuses and KVKs.”

Another option, according to other experts, is to remove any ban or bar on CR ownership. Logically, whenever select organizations are allowed and others are banned, there is scope for government discretion and favouritism. Such guidelines necessarily leave gaps that can be exploited. Sajan Veniyoor says that the current guidelines actually deter grassroots and community-based organizations. “The licensing procedure is designed to keep people out. Only the big NGOs with connections in the big cities can manage to get a licence, which takes an average of 3-4 years.”

Therefore, there is a case to give licences to any legal entity, as opposed to individuals. Even if this is done, and we agree that the CR tier of broadcasting should be open to everyone, there are questions about transparency which need to be addressed.

Spectrum holds the key

CR, like other categories of radio and broadcasting, needs spectrum, which is a scarce resource. So, even if any entity can own CR, how will the government allocate the accompanying spectrum? One choice is to give it on a ‘First-come, first-served’ basis.However, as the 2G-spectrum telecom scam showed, this may not ensure transparency. Powerful players manipulate such a process. This is especially true of CR because, under the existing guidelines, less powerful grassroots organizations find it difficult to apply. Thus, the chances of CR-capture by elite groups are higher under the ‘First-come, first-served’ route.

There is a need to make the entire licensing procedure completely transparent. This may entail a decentralised and digitised licensing process. In addition, there is a need to totally reduce the role of the government, once the various ministries and agencies, including I&B and the Ministry of Home Affairs, have done their scrutiny verifications of the applications and applicants. After this, only an independent and autonomous body shall be responsible for the final decision on CR licences.

Such a body, which can be a new form of a screening committee (but outside the purview of I&B), or an independent regulator, and possess powers to screen the applications, check the background of the organizations and the individuals behind them, and decide their legitimacy. All approvals and rejections, as well as the dissenting views, might be put in the public domain, possibly on the I&B Ministry or the independent agency’s website.

Strengthening the screening committee

The existing screening committee needs to be strengthened and given more powers and teeth. At present, the I&B Ministry has a Delhi-based screening committee. But for outsiders, and even the CR applicants, its working is mired in secrecy and mystery. There are no guidelines on how the members are selected or their tenure. There is no clarity on how it takes decisions, and how the internal conflicts or differing views between the members are resolved. The screening committee finds no mention in the official guidelines or other public documents. Yet, its role in application approval seems to be critical, although its recommendations aren’t always accepted by the I&B Ministry. .

The problem with the existing screening committee is that its role, function, composition and tenure are yet to be clearly outlined in the guidelines. These should include the eligibility and recruitment criteria for the members, procedures on how to document its deliberations and decisions, and the process to publish the documents received and generated by the committee. The reasons to award a licence, and the commitments made by the applicants, should be in the public domain. Similarly, the reasons for a rejection should be known to the public.

Also, an alternative model can be charted, with a focus on decentralising the licensing process in a different manner. Instead of a single, decentralized screening committee, appoint regional screening committees instead. Under the proposed model, once the central ministries give their clearances, the decision to grant the licence will be solely under the purview of the regional committees. This will help increase time efficacy, hasten the licensing process, make it more efficient, and enable robust background checks of the applicant at local level to prevent proxy ownerships.

Case for an independent regulator

At present, the I&B Ministry receives the applications, reviews, accepts or rejects them, allocates funds, monitors and penalises. There is a need to separate the licensing authority from the assessing authority and the authority in charge of punitive measures. This would mean the creation of two more independent and autonomous bodies – one as the assessing authority and the other with quasi-judicial powers and in-charge of punitive measures.

One can therefore propose a clear division whereby a state entity like the I&B Ministry, in tandem with Wireless Planning & Coordination (in the telecom ministry) are in charge of policy and all the regulatory and monitoring work – ensuring compliances, licensing, renewal of licences, monitoring and corrective measures – is handled by a single and an independent regulator.

One example of how this functions partially is in the telecom and TV broadcast sectors.The telecom ministry and I&B formulate the policies but also act like the licensing authorities. TRAI regulates the two sectors, but in a partial manner, and its appellate wing, TDSAT, manages the disputes’ management between the various stakeholders.

It’s in the interests of CR that such segregation is carried to its logical end and licensing is not just under the government’s domain but that an empowered screening committee outside the purview of I&B is also engaged in issuing licences. In the case of CR, the independent regulatory role can be given to TRAI. But this move will require the setting up of a separate licensing authority for CR. Needless to say, the licensing authority is empowered to weed out applications that don’t adhere to the spirit and letter of the CR guidelines.

Put the communities first

Vinod Pavrala, chairholder, UNESCO Chair for Community Media, says that the current CR guidelines are vague about the ownership issues. He explains, “We need to reduce the scope for vagueness and interpretations and implementation that seem to violate the spirit of community radio. The spirit is something, the (current) guidelines are something else.”

This is why a mechanism that prevents policy capture by the elites is imperative, as is the need to encourage the involvement of localized and marginalized groups in the CR segment. Any option that is finally agreed upon by the various stakeholders needs to ensure that the underlying objectives and philosophy of CR are not undermined by vested interests. As our study shows, this can happen in practice.

In each and every CR station mentioned in the study, it needs to be noted that the basic minimum level of compliance, i.e. the eligibility criteria, is satisfied. Thus, the violation is not in the process but in the spirit. Consequently, the scrutiny process needs to be revised and made more robust. This can be done through stringent disclosure norms for the licensees, which are insisted upon by the appropriate authority.

At the time of licensing, applicants can be mandated to share their administrative and financial details. The appropriate authority needs to actively look out for ways in which external interests can control CR (if at all). Further, all the disclosures have to be placed in the public domain (preferably on the I&B Ministry or appropriate authority’s website).

It is a decade since the last guidelines were formulated. Isn’t this the right time to take stock of the situation, do more thorough research in CR, and initiate exacting changes in the guidelines?

Ashish Sen, Advisor (Asia-Pacific Board) AMARC, says: “There should be more collaboration and alliance building between CR stations, policy makers, advocates and other stakeholders. These could be in the form of national or state consultations, which are action-oriented. Only then can we have a mechanism that will ensure the ‘right’ ownership of CR stations.”

This research was supported by the Inclusive Media UNDP Fellowship 2015 awarded to Devi Leena Bose and Anushi Agrawal.

Part 1