Five net neutrality myths busted

A savetheinternet.in media campaign on net neutrality

Last year was a remarkable year for popular debates on internet-related issues in India. It saw the public outrage against Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, 2000 culminate in a well-reasoned judgment delivered by the Supreme Court declaring it unconstitutional. The year also saw popular media discussion on the fraught issue of net neutrality snowball. Whereas in February 2015 the average person would not even have heard of “net neutrality” or “internet.org” (as Free Basics was called then), by December 2015 a large segment of internet users had a strong opinion on both schools of thought. And all this, thanks to a certain kind of media engagement with the issue which managed to break numerous hard-held myths about media debates. Here are a few of them:

Myth: People are interested in the sensational, not the technical.

Reality: People are extremely interested in the technical, if pitched right.

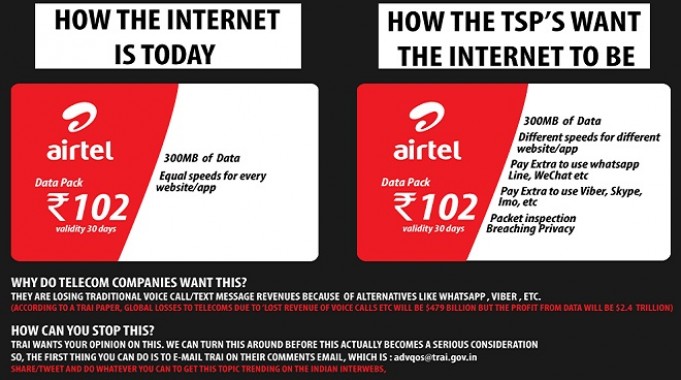

What is significant is that something which started as a rather technical, regulatory policy discussion has, within the short space of one year, managed to catch public attention in ways that technical issues are not thought to do. In August 2014 when Telecom Service Providers (TSPs) like Airtel demanded in an industry meeting that TRAI regulate competing Over-the-Top (OTT) services like Whatsapp so that what they deemed to be a “fair” regulatory environment could be established, people did not care less.

But come December 2014 and later, when Airtel decided to “fairly” charge extra for VoIP/Whatsapp usage, people had an opinion on numerous technical matters of regulation like licensing, zero-rating and net neutrality. This proves that people are interested in technical matters and not just the sensational, as soon as they are able to connect the impact of the technical upon their everyday lives.

If the media can pitch complex technological issues in a way that makes them relevant to ordinary people, as the savetheinternet.in and John Oliver’s video segment on net neutrality could successfully do, they will find that people always want a say in technical policy regulation - nobody wants to be left out of technical decision-making. When important governance issues fail to be debated publically, the reason often lies in the media’s inability to explain technical issues in a way which feels relevant to common people, and not the latter’s disengagement with technical matters. It is the former issue which the media should aim to address, rather than dismissing the public as stupid. The public is only as stupid as the writer is.

Myth: The public is wrongly informed and uninterested.

Reality: The public is imperfectly informed and is willing to fight for its interests.

The TSP conglomerate has been baffled at why so many regular internet users chose to respond to the TRAI’s original Consultation Paper of April 2015. The Cellular Operator’s Association of India (COAI) went as far as to say that traffic management data and techniques should not be shared with the consumer-citizen because such complex technical matters would only add to their confusion (page 15).

This is bullshit for the simple reason that we live in a democracy, and the very point of a democracy is governance by people for themselves. And such governance can only happen when common people are well-informed. The decades since the Second World War have increasingly seen a certain kind of reliance on “expertise” in deciding governance questions at the expense of democracy. This is not to say that seeking an “expert” opinion is in any way bad, but if such opinions are deployed in ways whereby the public does not comprehend what technological design it is consenting to, it can hardly be called a democratic process.

What is heartening is that once certain expert contributions to the net neutrality debate were made comprehensible to the public in an accessible language and formats, people were more than willing to participate through somewhat obscure governance mechanisms such as public consultations to fight for what they understood as their interest.

That being said, the net neutrality debate might not have been explained to people in all its complexity within the popular media, but even with the imperfect information they had, the public responded most enthusiastically, not cynically, and what else can be more hopeful for the future of a democracy?

Myth: Nobody opposes net neutrality.

Reality: Net neutrality is an improperly defined concept in public debates.

What is net neutrality? Who knows! One theory is that it provides a level playing field for both established internet companies and new entrants. Does this mean that companies which send out spam should have an equally level playing field? And if not, how does one create a regulatory design which minimizes only spam and not legitimate internet content? Will such a design be a violation of net neutrality? Opinions differ. Another floating understanding of net neutrality seems to imply equal internet access to everyone. But people who pay for a different plan also access different speeds of internet. Is that a violation of net neutrality? Opinions differ.

It is all because there is little consensus in the popular media yet about what constitutes this elusive “net neutrality.” Sure there is a certain understood definition for “net neutrality” among techies, but that often falls apart when faced with different kinds of business interests. Anyway why should the public choose either definition when it can carve out its own? It is in the nature of definitions and concepts to evolve with the needs of people and when they fail to do so, they are clearly dud concepts.

The upshot is that net neutrality is, happily, an evolving concept in public debates. But confusingly, this can also cause all sorts of communication gaps. So while TSPs like Airtel, Facebook and Savetheinternet.in all say they support net neutrality, they mean quite different things by net neutrality, with each claiming that theirs is the “true” understanding of net neutrality.

COAI’s version of net neutrality manages to support zero-rated apps by defining itself as: “No denial of access and absence of unreasonable discrimination on the part of network operators in transmitting internet traffic." (page 9). This contradicts Savetheinternet.in’s version of net neutrality which is about preventing ISPs from providing a competitive advantage to any internet service/app either through pricing or Quality of Service, which rings the death knell for zero-rated apps. Facebook’s understanding of net neutrality respects this fair competition in general but makes an important exception for “essential” internet apps designed “for the poor.” As citizens, we need to decide for ourselves how to define net neutrality in a way which aids maximization of a gamut of public interests, including fair competition, low pricing, choice and access.

Myth: Free Basics will improve internet access in India.

Reality: It is difficult to predict without any hard, empirical data corresponding to the Indian context.

Briefly, the state of unbiased public research into user habits and the numbers associated with how people access the internet in India is in a shambles. There exists a 2015 study conducted by Amba Kak of the Oxford Internet Institute in this matter, which tells us that low-income consumers in Delhi want to access the entire internet when they do. Nikhil Pahwa of Medianama has used this study to back the claim that Indian users do not want Facebook Free Basics. But conversely, this study can also be used to claim that Indian users will reject Free Basics, and therefore there is no need for an additional net neutrality regulation from TRAI because the market will correct itself. Possibly.

My point is that in the absence of specific data, it is hard to say for sure which direction potential Indian users of Facebook Free basics will turn - will they use it, will they not, will they like to use it, will it improve access given how Indian users utilize the internet and given what they expect of the internet? We do not know for sure. What we as the public can only do is make educated guesses with the small sample of publically available data. And upon such educated guesses, we can choose to frame policy. Such opinions, coming from either Facebook or COAI, or savetheinternet.in then become a matter of personal inclinations in historical interpretations and risk aversions.

It is in this spirit that the UPenn-based internet academic, Christopher Yoo advocates waiting to see how differentially priced markets like those offering zero-rated apps act, before framing policy in this regard. And it is in the same spirit that Sunil Abraham of the Centre for Internet and Society, Bangalore justifies the opposite - precautionary, principle-based regulation in the absence of data.

The critical question remains: What do we want to do in the absence of data? The most obvious response to this is fund the creation of public data on the issue. There seems to be little movement in that direction from either the TRAI or the DoT. There needs to be a greater public demand for this. That being said, the creation of new public data on internet usage in India can only be a long-term response. What do we do now? To be honest, the importance of taking a decision on this right now only exists because of commercial pressures. While business is important, how far, as citizens, do we want to give into these pressures to make a hasty choice?

These are important questions we need to debate. But whatever we choose to do, it is important to be aware of the circumstances we are making those choices in, so that when the circumstances change, we have the free understanding to change our choices.

Myth: The Indian media finally spoke up for the public interest.

Reality: The Indian media spoke up for its own interests, which might have a few intersections with the public interest.

One of the popular stories going around the Indian media is that big, evil, foreign corporations want to destroy “net neutrality” in India and we need to fight them. Conversely the Facebook story is that it wants to help India to connect; it is no big, evil corporation but a benevolent philanthropic organisation.

The reality, as usual, is way greyer. The truth of the matter is that net neutrality, like life, is not a Lord of the Rings movie with a good versus evil battle. It is true that good versus evil makes for an easy story to tell (I also call it lazy storytelling), but it has very little to do with facts. And the fact is that some big corporations including Facebook and big TSPs like Reliance or Airtel might want to undermine a certain version of net neutrality given their business interests, and these interests can sometimes hurt a citizen internet user, and sometimes not, and may sometimes even help.

Considered comprehensively, the public interest lies in simultaneously maximizing innovation in both TSP and OTT markets, increasing internet access (by building infrastructure, reducing access prices, increasing access speeds), increasing media diversity on the internet, maintaining high, equal and fair competition in both TSP and OTT markets as well as low barriers to entry and, lastly, ensuring that internet content is not censored either by private companies, the government or anyone else.

The reality is that absolutely no media debate is currently asking how can we design a governance mechanism which maximizes all these public interest parameters together? The reason is that the media (and within it different kinds and scales of media) is differently affected by such governance mechanisms because of differing interests from the public.

Much of the media industry might be interested, like the public, in maintaining competition and innovation but media diversity and battling censorship, for example, are not always a direct concern of the industry simply because such investments don’t give financial returns, and financial returns is what businesses are about. The public, on the other hand, is about much more.

It is sad but expected then, that popular, contradictory, but well-intentioned media campaigns like savetheinternet.in or Facebook Free Basics which try to speak in the name of the public interest, end up ignoring the complex nature of this interest. Each side justifiably advocates only those portions of the public interest spectrum which favour its own sustenance. In short, the public debate on net neutrality we are having right now is really a struggle of interests between established TSP/OTT corporations and upcoming startups.

Media campaigns which try to speak in the name of the public interest, end up ignoring the complex nature of this interest.

Sure, some the arguments of each favour certain aspects of the public interest (like Free Basics’ public interest angle of internet access or Savetheinternet’s public interest angle of equality) but neither of them is about the public interest as a whole, or per se.

The current media debate is not positioned in the public interest, rather certain ideas of the public interest are being read into the media industry’s own, often fraught interests. As citizens, rather than getting swept away by one camp’s arguments, we need to discern and separate our interests from the positions of all camps.

Smarika Kumar is a legal researcher who was until recently with the Alternative Law Forum, Bangalore.