The online obsession of the #DhakaAttack-ers

The bloody terrorist operation in Dhaka, Bangladesh, which ended in the early morning of July 2 and in which 20 people were killed, was deliberately turned into a prolonged hostage standoff because the terrorists wanted to internationalise the mayhem through social media and sow fear in the hearts of those watching -- and reading.

By now we know the first names and photos of five young gunmen -- Akash, Bikash, Don, Badhon and Ripon – although six attackers were killed, and the seventh held by security forces. This article also has a picture of Nibras Islam.

The photos of these young Bangladeshi boys were first uploaded by the Islamic State (IS) official news agency Amaq, and then shared by the SITE Intelligence Group. Their Facebook posts are windows to the lives they led (since deactivated), telling us of the upper-class schools they attended (Scholastica, in Dhaka) and the universities they were enrolled in (Monash University in Malaysia).

One of the attackers, Nibras Islam, had a Twitter account, on which he had posted several tweets in late 2014, indicating that he was involved in a love affair gone wrong.

Bangladeshi authorities say the local boys are members of the Jamaeyutul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB), an organization which has been banned for more than a decade. But Islamic State (IS) claimed the killings early on.

Indeed, several analysts who write on jihadism and terrorism, such as Amarnath Amarasingham, a fellow at George Washington University’s Program on Extremism, as well as Rukmini Callimachi, the New York Times’ correspondent in Paris, veer in favour of the IS claim.

@rcallimachi, who reported the November 2015 Paris attacks and travelled to several parts of West Asia following the IS insurgency, says the #DhakaAttacks are similar to the Paris attacks in several ways.

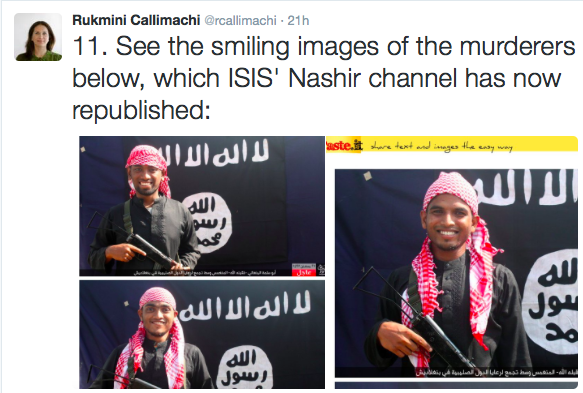

First, there was considerable planning. The #DhakaAttackers took pre-attack photos of themselves next to the IS flag, which were then posted by ISIS Nashir channel, she says.

“The information they fed out went straight to ISIS’ core media operation, appearing in close to real time on ISIS’ Amaq News Agency,” Callimachi adds on her Twitter timeline.

Second, like in the Bataclan concert hall in Paris on November 13, 2015, the attackers in the Holey Artisan Restaurant in Dhaka knew they had a mission to accomplish.

Witnesses in Paris remember they saw attackers try to get online, says Callimachi.

Dhaka was, in fact, one step ahead of Paris. The attackers not only got images of the operation out, such as photos of bodies of victims lying next to the rattan chairs in the bakery, but also details. For example, they were right when they said that 20 hostages had been killed.

According to an account of the hostage situation in the New York Times , the attackers told one of the restaurant’s cooks, Sumir Barai, they would only kill foreigners, not Bangladeshis.

Mr Barai, who had been hiding in the kitchen, came out and saw that the six-seven bodies on the floor were foreigners.

But as he told the NYT :

The gunmen, he said, seemed eager to see their actions amplified on social media: After killing the patrons, they asked the staff to turn on the restaurant’s wireless network. Then they used customers’ telephones to post images of the bodies on the internet.

Amarnath Amarasingam, @AmarAmarasingam, who has been studying Western foreign fighters for the last couple of years at the University of Waterloo, explains why social media – and especially Twitter – has become a key weapon in the battle-hardened armour of the active IS fighter.

First of all, says Amarasingam, Twitter is an incredibly easy tool to spread information (or disinformation, whichever you prefer), which is why IS social media accounts used to flourish.

But Twitter has since caught on, and has been suspending accounts of fighters and supporters alike.

Abu Ahmad, an active IS supporter online – not his real name -- told Amarasingam he has had over 90 Twitter accounts suspended, “but is not planning to slow down.” He says he has found several ways to return online, each time.

“I follow people, and they follow me back. We do shout outs,” Ahmad said, adding, “we also have secret groups online which don’t get suspended, and we share our new accounts on there.”

He admitted that he and his friends also hack accounts, especially those with weak passwords.

“We then change the password and clean the account. We change the profile picture, the cover picture, and delete all the old tweets. Then the account sits on a list until someone needs it. I used to spend the night doing that,” Ahmad says.

When you spend so much time together, points out Amarasingam, you create an online family, with the emotional and social benefits that real-time families give you.

As the Dhaka siege wound down in the early hours of July 2, an unnamed individual posted several short bursts of video on Facebook. Bangladesh’s biggest English newspaper, The Daily Star, combined them together and posted them online.

Watch the scene at the restaurant before the Bangladeshi forces moved in – you can see one attacker with a backpack – and after here.