The Yogi and the Commissar

Book review

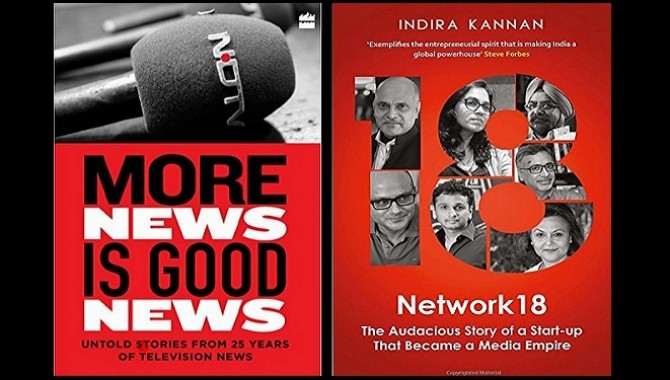

More News Is Good News: 25 Years of NDTV, Edited by Ayesha Kagal, HarperCollins Publishers India, 2016, 392 pages, Rs 799.

Network 18: The Audacious Story of a Start-up That Became a Media Empire, by Indira Kannan, Penguin Random House, 2016, Rs 699.

NDTV celebrates its 25th anniversary with More News is Good News: Untold Stories from 25 Years of Television News; and Network 18 marks the transition in its ownership with the unimaginatively (if correctly) titled Network 18: The Audacious Story of a Start-up That Became a Media Empire. To be accurate, though, it is not Network 18 but its previous owners who are marking the transition.

It is interesting how true to type the two books are: the one, self-absorbed and self-satisfied; the other, racy and somewhat breathless.

The man doth protest too much

The NDTV book is high-school-year-book-meets-corporate-brochure. A collection of pieces by employees and associates recalling the wonderful times they have had, proud of and grateful for the privilege of belonging, and with an underlying note of the superiority of NDTV. High professional standards, ethical, principled. It never did anything wrong, and rarely made a mistake.

Prannoy Roy sets the tone in his opening piece. He presents NDTV as the brave victim of a corrupt environment, standing proud, bloody but unbowed, and makes a virtue of the company’s poor performance in both ratings and profits.

Each of the company’s three news channels – NDTV 24X7, NDTV India and NDTV Profit – was once the leader in its genre but has not been for years. Roy’s contention is that this is so for two reasons. One, because NDTV has refused to prostitute itself for ratings. Two, because the ratings system is both inadequate and manipulated by unscrupulous broadcasters. To anyone who has known the news broadcasting business in India, that is a familiar refrain.

It is not as if there has been just one ratings system in the country. During NDTV’s life as a broadcaster there have been three. First there was TAM. When NDTV began to slide down in TAM ratings, along came aMap, which showed it in a much stronger position. So while TAM was the industry standard, they switched to citing aMap, slicing and dicing the data to claim leadership.

When, in time, their channels slid down in aMap too, they ran a campaign citing three unnamed “major surveys across India" to claim 60% viewership among an undefined audience. Contrary to standard professional practice, the ads did not detail where, when, and by whom these “major surveys” were done, or the defining parameters. Coming from a company that has its origins in psephology and counts among its brains trust Dorab Sopariwalla, the senior-most market research professional in India, it seems unlikely that this was out of ignorance or an innocent oversight.

In 2012 NDTV sued TAM’s parents Nielsen and Kantar for $1.3 bn in a New York court on charges of deliberately publishing corrupt and tainted data, favouring rival channels in return for bribes. The claim included compensation for loss of revenue over a period of eight years, the amount on that account reported variously in a range from $680 mn to $810 mn. Calculating even at an average of Rs 50 to $1 for an amount of $700 mn, that is Rs 3,500 crore or an average of over Rs 400 crore per annum in loss of revenue.

In the event, the New York court dismissed the case and nothing has come of it thus far.

Now TAM and aMap (which had closed earlier) have been replaced by BARC, a ratings provider set up jointly by the industry bodies of broadcasters, advertisers and advertising agencies. BARC data for Week 40 of 2016 (1st to 7th Oct) show NDTV 24X7 with a share of 12% is fourth of five English news channels; NDTV Profit with a share of 13% is fourth of five in English business news; and NDTV India is not in the top five in Hindi news. So it would seem all ratings systems are either inadequte or manipulated.

No, wait. There’s hope yet. “Another benchmark is the BARB in the UK, which just came out with their ratings that NDTV 24x7 is India’s Number 1 news channel ahead of Aaj Tak and ABP,” said Vikram Chandra, CEO, in an interview to Impactonnet. Doesn’t BARB measure viewership in the UK, though, not in India? Ah, I get it. NDTV 24X7 is the most viewed Indian news channel in the UK – not quite India’s Number 1 news channel, as Chandra would have us think.

The issue is not low ratings; it is that NDTV can neither improve the ratings nor live with the fact. It does not become a self-appointed moral standard bearer to constantly moan about how unfair the world is.

The Sermon on the Mount

Roy informs us that NDTV operates by what they call (“rather pompously”, he admits) the “Heisenberg principle of journalism”. Paraphrased, it means that for a news organization, profits and integrity are in conflict. “Almost by definition, the path to making profits for a news organization is littered with compromises that change the nature of journalism, often so that it can no longer be recognized as a news channel,” he says, and goes on to describe three: going tabloid; fiddling the ratings; and blackmail and extortion.

NDTV, of course, does none of these reprehensible things, which is why it is not profitable.

Dismissing all Hindi news channels (except NDTV India) as tabloid, Roy contends that advertisers, advertising agencies, CEOs and marketing heads watch only English channels, “so all decisions on advertising rates and expenditure are based solely on the number of eyeballs, not on the quality of the channel, because nobody has watched any Hindi channel.” Unlike the UK, he says, where a quality media vehicle gets “a much higher advertising rate per eyeball than a tabloid”, in India it does not.

Again Roy conveniently, and disappointingly, ignores the facts.

BARC reports that in Week 40 of 2016 Aaj Tak generated 164.58 million impressions; Times Now, 1.34 million; and NDTV 24X7, 331,000. If advertisers were to pay all of them the same rate per 1000 impressions – as they logically should – NDTV 24X7 should earn a price per 10 seconds that is 25% of what Times Now does; and 0.2% of what Aaj Tak does. Roy knows far better than I do what kind of rates each of them gets today, but I have no doubt NDTV 24X7 gets far more than the number of impressions would warrant.

NDTV’s lasting contribution to Indian broadcasting – not just news but all broadcasters – does not find a mention in the book: the infamous placement fee which financially crippled Indian broadcasters, including NDTV, and continues to.

For the uninitiated, in the old days when TV distribution used analogue technology, it offered limited bandwidth. (Remember when you had no set top box and the channels showed up on your TV in a seemingly random order?) Those with top-end TV sets could receive 106 channels in theory, but fewer than 60 with reasonable (for then) clarity; and at the other end, the rank-and-file could see 11 clearly, and a total of 36 at all. Hundreds of channels competed to buy those positions, simply so they could be seen, and obviously the ones with the deepest pockets got them.

Over time the practice grew to such proportions that for many broadcasters – and certainly for news broadcasters – the placement fee became the single largest line item in their P&L. Distribution became the first priority for the allocation of funds, ahead of content and salaries. While the biggest networks – Star, Zee, Sun, Network 18, Sony – got into the distribution business themselves, cutting their own costs and making money to boot, all but the big five have been bleeding for years.

Digital technology will put an end to this extortionate practice, which is why the cable trade has resisted the efforts of successive governments and continues to stall digitization in large parts of the country. That is the reason for those syrupy ads on TV sweet-talking viewers into getting a set-top box. No government can afford to arm-twist cable operators, who are politically important at the local level, so they keep pushing the digitization deadline (now it’s 31st December 2016) and cajoling viewers.

It is widely believed in the TV business that the initiator of this practice was NDTV, and there is enough anecdotal evidence to support the belief. One view is that they did this to prepare for and support the 2005 launch of NDTV Profit, going up as they were against the entrenched CNBC-TV18. But a key NDTV player of the time, who was in the thick of it then, told me years afterwards that it was earlier, to ensure the visibility of their channels prior to their IPO in April 2004.

For all his protestations, Roy goes on to accept that “on balance our news media and its ‘soft power’, both television and print, have been working for democracy.” But, he cautions, we are hurtling towards a regulatory cliff, and that is when governments try to take control. “…the time has come once again to fight any encroachment by the government and to act before it is too late,” and, later, “…any changes in the media environment must be initiated and guided by journalists, in dialogue with the judiciary, not with or by the government.”

Instead of these and similar broad statements about the way things should be, it would have been good to know what Roy and his colleagues have done about these issues. Leadership means walking the talk, not just sermonizing.

Missed opportunity

The rest of the book is detail. Vishnu Som’s piece Reporting Under Fire, reminiscent of the writing of John Simpson, stands out for actually sharing the experience: the trials and tribulations, the frustrations, the limitations, and the triumphs. That is the kind of first-person inside story you want to hear.

Barkha Dutt, who must have much to share, has only her script for a show she did to mark the tenth anniversary of her Amanpour moment, her coverage of the Kargil war. Amusingly, the script is reproduced in its entirety, complete with marginal notes and directions like these:

- “Start with an abstract close-up – a flower, a bit of a stream, and not a mountain long shot”

- ”Bite – Vishal, brother of Vikram, doesn’t speak very clearly – so have to see if this works”

- “Slow-mo shots of us looking at mountains together”

You’re left wondering whether this is due to vanity or simply poor copy checking.

The book is a missed opportunity – for the reader, if not for NDTV. This is not just any 25-year old company. It is a company that was in the forefront of one of the biggest, most fundamental changes this country has seen, without which democracy was a joke. A couple of pieces recalling the clunky, makeshift operations of the old days are interesting and amusing, but there is regrettably little by way of insights, or of sharing of what must have been the excitement – sometimes heady, sometimes tense – of pioneering private news television in the country in the teeth of paranoid regulation.

Network 18’s mea culpa

If the NDTV book is about what’s wrong with the rest of the world, the Network 18 book is a confessional: “a story of brilliant ideas, severe setbacks, naked aggression, spectacular victories and fatal flaws”, as a cover blurb describes it. Written – very competently – by Indira Kannan, a former Network 18 journalist, it obviously has the full approval of Raghav Bahl, who also holds the copyright to it.

The rise and fall of his empire was fraught with questionable practice, but with Network 18 now behind him, Bahl has nothing to lose on that front and tells it – or lets it be told – like it is. Detractors and those in the know will inevitably have different versions of incidents, but to the outsider this is a dramatic story candidly told.

Bahl in his foreword writes with angst about losing control of Network 18. “With such enviable achievements, why do I still ask, ‘Did I succeed?’ Because I eventually lost control… A far more important question than, ‘Did I succeed?’ for any first-generation entrepreneur is, ‘Why did I fail?’ I can answer that for myself with hindsight candour. It was a lethal mix of hubris, unrealistic ambition fuelled by reckless debt, and the misplaced belief that I could tame any crisis.”

It is creditable that up front he takes full responsibility for the denouement. There will no doubt be those who question the detail, but it is unlikely anyone would argue with Bahl’s ownership of the outcome.

Adventure and misadventure

The tie-up with CNN was quite a whodunit in itself, starting with pulling it out from under NDTV’s nose. Full credit is given to Haresh Chawla for the whole gutsy, brazen process from the idea to the closure, and to the surprising, little-known role of Subhash Chandra in facilitating it.

The launch and success of Colors – now the no. 3 channel in India, after Sun and Star Plus – is a story of guts and glory. NDTV Imagine, Real and 9X had been dismal failures. Why would there be room for yet another Hindi GEC? Colors set out to be big, and pulled out the stops in content, distribution and promotion. It started with big shows, upped the ante on distribution – the broadcasting industry was agog with whispers about how much they spent – and invested heavily in advertising and promotion.

But, as I wrote elsewhere at that time, it is not enough to have the resources. It needs the risk appetite to put money, careers and reputations on the line, and then the energy to fight every single day to keep your place at the top of the league table. Chatting to Haresh Chawla when the launch of Colors was imminent, I remarked about the huge amount of money they were known to be spending. “Paise to phir kamaalenge,” he said. “Izzat ka kya hoga?” (“We’ll earn the money again, but what about the loss of face if we fail?”)

For all its successes, Network18 lurched from crisis to crisis, most often of its own making. Having never been known to take time off, “In 2007, finally, [Bahl] would take leave – unfortunately, however, it was of his senses…” Global Broadcast News had had a madly successful IPO, but ambition, impatience and liquidity make a deadly cocktail. Even while deep in debt, between 2009 and 2011, TV18 managed to raise Rs 1,000 crore in equity.

“Stuck in a deep hole,” Kannan writes,“[they] had managed to get their hands on a 1000-crore-rupee ladder…. Instead of stepping on the ladder, Raghav and his managers decided to widen the pit.” And so instead of paying off their debt they blew up the money on Homeshop18, Firstpost, and a new Hindi movie channel.

That, says Bahl, was when they lost Network18. What happened later (borrowing from Reliance and their conversion of the debt into equity) was, he says, only the singing of the dirge. In his narration of the process of losing control there is no rancour, only regret. He takes full responsibility for what happened, and says Reliance did nothing more than they were entitled to within the framework of his agreement with them.

In the course of its growth from a production house to a media empire, Network18 developed a highly questionable ownership structure. Each time they launched a new channel – CNBC Awaz, CNN-IBN – they set up another company and stock analysts complained that Bahl was siphoning off value from TV18. Bahl blames “outrageous” rules regarding foreign equity, because of which the only way to get each licence was to launch another private company, off TV18’s balance sheet.

Equity analysts don’t buy that argument. Nikhil Vohra, CEO of a venture capital fund and one of the first analysts to follow TV18 and Indian media stocks, says the complexity and opacity of the group’s structure was unwarranted.

“It is completely untenable to suggest that it’s the government which forced them to do what they’d done,” he is quoted as saying, and that investors “just lost complete faith in what Raghav was doing”, diminishing the company’s ability to raise equity and forcing Bahl to support the business with debt.

Asked earlier by Shuchi Bansal of Mint (in an interview published as an appendix in the book) what his compulsions were to sign the Reliance deal, Bahl says, “We were in a classical debt trap. Our market cap had come down to Rs 400 crore; our debt was Rs 2,000 crore plus. So a debt to market cap ratio of 5. We would not have survived.” But the debt trap was not something that happened to them: it was of their making.

Bahl does say that in terms of delivering value to shareholders the company was an ‘absolute and abysmal failure’, and that, “None of these analyst things would have happened if we had actually put the shareholder first.” Too little, too late.

Ironically, a company built on a foundation of reporting and analysing business and the stock markets was sinking because of some of the worst practices of listed companies: opaque structures, siphoning off shareholder value, and a cavalier attitude to public money. It was this attitude that led to many infractions such as buying Infomedia without due diligence, for example, or going into huge contract negotiations without legal advice.

All credit to Bahl for letting it all hang out, for taking the responsibility, and for letting his views on many issues be presented as just that: as only his views, along with others which don’t necessarily agree with his, including, on the Indian Film Company fiasco, his sister’s. While it has its place, that doesn’t detract from the rights and wrongs of what he did, by commission or by omission.

What Kannan has written, and Bahl has authorised, is much more than the biography of an entrepreneur or of a broadcasting network. It is instructive reading for any entrepreneur, indeed, for any CEO, whether owner or professional. There are of course lessons in what Bahl did – the boldness, the risk taking – but the more valuable lessons, perhaps, are in what he did not or did wrong, not just as a rookie entrepreneur but even at the height of his high-profile success. The latter is scary, and a warning to every CEO.

Different strokes…

The timing of the two books is fortuitous, enabling as it does an illuminating comparison of two leaders, of two organisations, following a path much the same in many ways and at about the same time, but in two very different ways and with very different outcomes.

Interestingly, these books come hard on the heels of the publication earlier this year of the autobiography of Subhash Chandra, perhaps the original television trailblazer, from yet another background and with yet another personality and style.

For those interested in television, especially for those who have been associated with the business and have known the players, this has been a year of rich reading. But among all of them the Network 18 story stands out for the important messages it holds for anyone who runs a business.

Note: Title from Arthur Koestler, The Yogi and the Commissar (1945). The Commissar, at the materialist end of the spectrum, uses any means necessary, while the Yogi's emphasis is on ethical purity, not on results.

Disclosure: As a news broadcasting executive the author competed with both NDTV and Network18 across genres of news. He was also associated with TAM as a member of the TAM Transparency Panel.

Chintamani Rao is a strategic marketing and media consultant who has managed and built three news channels—Times Now, ET Now and India TV.