Two years of Modi Sarkar—ring out the reporters!

Picture tweeted by the PMO

Last December, Prime Minister Narendra Modi broke a huge piece of news from his Twitter handle. He declared, quite out of the blue, that he was stopping by in Lahore on his way back from Kabul to meet and greet Pakistan Premier Nawaz Sharif on his birthday. The Pak visit was the first by an Indian Prime Minister in 11 years. And the country’s media got the jaw-dropping news, not from a special press briefing by the ministry of external affairs, but straight from the PM himself.

Modi, who is an avid tweeter and has a follower count to rival that of a rockstar (19.8mn on @NarendraModi and another 11.1mn on @PMOIndia), tweets relentlessly about the government’s policies, programmes and achievements. On occasion, he delights in making some big-bang announcement: he also used Twitter to break the news that US President Barack Obama would be India’s guest of honour at Republic Day, 2015. It was a big deal, and his gazillions of followers on Twitter learnt about it simultaneously with the denizens of traditional media.

It is not just the Prime Minister, however. In the two years that the NDA government has been in power — the second anniversary of Modi Sarkar falls on May 26 — one of its stunning achievements has been the clinical efficiency with which it has engaged directly with the people across a whole range of media, especially new media, platforms. Today, every ministry and its minister has a Twitter account and a Facebook page with follower counts that run into thousands, if not millions. These are constantly updated and they dispense a steady stream of information on the programmes and performance of the ministry in question.

Some ministries, such as external affairs (MEA), railways, information and broadcasting, human resource development, women and child development and finance, have their own YouTube channels as well. They showcase videos, perhaps the most powerful media tool of all, on their work. Even the Press Information Bureau (PIB), the interface between the government and the media, deploys the whole spectrum of social media platforms to inform not just its traditional target audience, but also the public at large.

These, together with the government’s citizen engagement platform, MyGov.in (which is also a repository of data on the work and performance of every government department), the Prime Minister’s monthly radio address to the nation, Mann Ki Baat, and so on, form a massive, multi-pronged, state media juggernaut with phenomenal public outreach.

“The government believes that all modes of communication should be used. It’s a 360 degrees communication strategy,” says Arvind Gupta, the BJP’s national head, information and technology. “The thrust on social media is because it’s very spontaneous, fast, low cost, it has huge reach and above all, it appeals to the youth. This is a digital-first media ecosystem and we want to use it effectively.”

Picture tweeted by the PMO

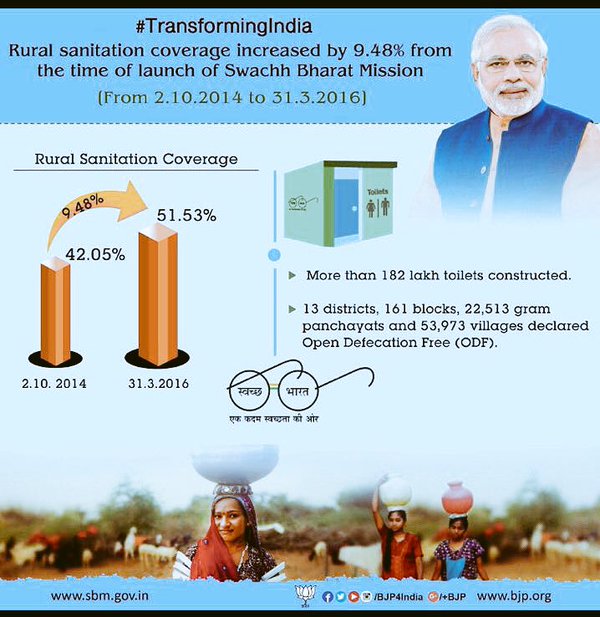

That’s exactly what the government is doing — steaming ahead, from hashtag to hashtag, and whipping up a blizzard of likes, shares and retweets. The Ujala scheme (under which LED bulbs are being distributed by the government) will reduce consumers’ bills by Rs 40,000 crore, tweets energy minister Piyush Goyal (729.1K followers); the government has disbursed Rs 62,000 crore as cash benefits under 59 central schemes to 30.78 crore beneficiaries in 2015-16, declares minister of state for finance Jayant Sinha (101.6K followers) on Twitter; Birender Singh, minister for rural development, panchayati raj, drinking water and sanitation, tweets that 95.6 per cent of the 1.87 crore toilets built under Swachh Bharat to date are already in use. Singh’s followers are a paltry 7,911. But his tweet will likely be retweeted by all his colleagues, shared by MyGov.in, and perhaps by the PM himself, until the chorus of that nugget of Swachh Bharat data becomes too loud to be missed.

Traditional media — newspapers and television — may or may not cover or follow up such news. The point is, the government is able to put out an avalanche of information in the public domain anyway, and put it out in exactly the manner it wishes. Thanks to the new media environment, the state seems to have made reporters somewhat irrelevant — at least, when it comes to disseminating news about its own performance.

How much the dissemination is absorbed however varies. The Human Resource Development ministry website uploaded 101 videos. The views for these are in 100s. The subscribers it has are 2,292. The Ministry of Women and Child Development uploaded 10 videos six months ago and nothing since. Views for nine of these were below 40, and for the 10th, 606. The Finance Minister’s budget speech uploaded on Feb. 4 has 49 views. This channel has 3035 subscribers.

Last month, there were reports that the Group of Ministers had recommended that the Modi government should make films highlighting its schemes and achievements and that these should be shown before every film screening in theatres across the country. Although officials hastily denied the reports, such a recommendation would have tied in with the way the current government aggressively promotes itself through the various media channels at its disposal.

Needless to say, the government has every right to publicise its work. After all, whether or not it is voted back in 2019 depends on the public perception of how well (or ill) it did its job. Giving citizens access to so much information about its plans and schemes can’t be a bad thing either.

However, there is a flipside to this. Many journalists are of the opinion that Prime Minister Modi has set a trend of communication that’s one way. From the latest statistic on the Jan Dhan Yojana to the newest initiative on cleaning the Ganga, from that new train connecting a remote area to the progress on the smart cities project — there is a truckload of information being incessantly deposited on social media. But if you want to look beyond the instant karma of digital dissemination and question anything, the doors are largely closed.

Says Sankarshan Thakur, senior journalist and roving editor at The Telegraph, “The PM himself doesn’t interact with the media at all. He talks straight to the people, over the heads of the media. What he bypasses as a result is the whole and necessary process of questioning.”

Indeed, there is a perception among journalists that despite the impression of transparency that the government gives, in reality, ministries and their ministers have become much more circumspect about talking to the media. Even the Prime Minister’s Office does not have an official spokesperson anymore — at least not one who is seen or heard. The office of a media adviser to the PM has also not been filled. Overall, there seems to be a deliberate attempt to restrict journalists’ access to the government. As Thakur puts it, “The system has become very opaque.”

Reporters routinely complain of the fact that more often than not, bureaucrats too are loath to speak to the media, no doubt under instruction from those on high. When this correspondent tried to talk to L.R Vishwanath, additional director general, New Media Wing, under the I&B ministry, for this article, she was told that he was not “authorised to speak to the media”.

Of course, the government stoutly denies any such design to exclude journalists. Says Frank Noronha, director general, PIB, “The truth is, whatever information with regard to policies, programmes and achievements of the government is there, it is being made available to everybody, including the public. The age of exclusive information is over.”

An ordinary citizen skimming through the government’s social media sites might agree. More so because they seem to make the state less remote, more approachable, almost a benevolent mai-baap. Foreign minister Sushma Swaraj and railway minister Suresh Prabhu, with 5mn and 885.2K Twitter followers respectively, regularly respond to and take action on SOS tweets from the people. When help is just a tweet away, it’s a powerful government-to-citizen connect.

And every ministry is working to strengthen that connect — without go-betweens like newspapers and private television channels. Take the MEA, for instance. It posts videos of media briefings, details of diplomatic visits, pictures, documentaries on Indian art and culture in the context of foreign countries on its MEA India and Indian Diplomacy channels, which are spread across Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and even Instagram. With more than 1.2m followers on Facebook, 1.3m on Twitter, and 43,000 subscribers on YouTube, MEA is clearly doing something right. In fact, its efforts on this score have been so successful that recently India was ranked 7th among nations in terms of digital diplomacy performance over the past year by Diplomacy Live, a global research and advocacy platform.

"We use a combination of platforms to reach out to the public,” says Vikas Swarup, joint secretary and spokesperson of the MEA. “We have also started using Google hangouts as an important tool,” he adds. For instance, earlier this year the ministry did a Google hangout on the Akshay Kumar starrer, Airlift, which, the government felt, had distorted facts about Indians being evacuated from Kuwait after Saddam Husain’s tanks rolled into the country in August, 1990.

Again, consider the portal MyGov.in, which was launched in July 2014 as a platform to get citizens to participate in the work of nation building through discussions, tasks, contribution of ideas and so on. Its 1.93mn registered members are a testament to the enthusiasm with which people have received this attempt at participatory governance.

“Our primary activity is engaging with the people on policies and programmes as well as crowdsourcing of ideas for governance purposes and recognising citizens who have contributed ideas,” says Gaurav Dwivedi, CEO, MyGov.in. The portal features discussions, polls, surveys, a blog section containing “editorials” from ministers — such as HRD minister SmritiIrani holding forth on the work being done on the New Education Policy. “The whole business of engaging with citizens cannot be done in a straitjacketed manner; it has to involve a range of methodologies,” says Dwivedi.

Experts agree that the government’s use of social media today is extraordinarily strong and integrated. "It’s the Modi government’s primary, direct communication channel--instant, powerful, and largely one-way,” says digital media analyst Prasanto K Roy. "It is in fact a continuation of the BJP’s Mission 272+ strategy of 2013 when it began using multiple digital platforms to reach out to the public in its bid to win an absolute majority in the 2014 elections.”

Speak to anyone in the government and he or she will insist that by communicating directly with the people, the Modi dispensation is really democratising the availability of information. “Our government believes that it must not be privy to just a few journalists,” says Arvind Gupta.

But surely in a democracy the Fourth Estate too has a very important role — that of questioning the state and taking it to task for its lapses? It has the role of amplifying voices that are not necessarily laudatory, but also critical. In this mostly one-way information super highway built by the government, there is little room for that.

“We are not replacing the media — we are adding to it,” says Noronha of PIB. “Reading anything more into this is merely a part of your own sensational requirement.”

But what that doesn't explain is, if one-way communication becomes the norm, how can the media do its job: asking questions and holding the government accountable?

The writer is a senior journalist.