A war photographer's erratic saga

A Pulitzer prize winning war photographer recounts her experiences in different war zones.

AVNEESH KUMAR liked the book - part war chronicle, part autobiography - in parts. Pix: Amazon.com

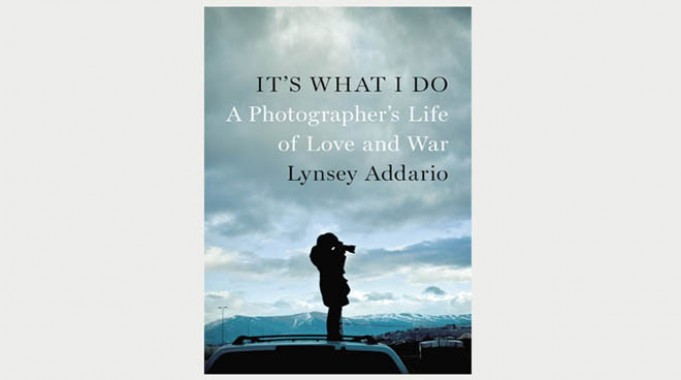

“It’s What I Do: A Photographer’s Life of Love and War”, Lynsey Addario, Penguin Press, ISBN 978-1594205378, 368 pages, Rs 1,887

The war photographer, Tim Hetherington, once said, “I want to record world events, big History told in the form of a small history, the personal perspective that gives my life meaning and significance. My work is all about building bridges between myself and the audience.”

What Hetherington said seems accurate to describe the urge of Lynsey Addario, the Pulitzer Prize winning war photographer. She took it as her responsibility to educate people and make an impact, to ‘convey beauty in war’. And her memoir, It’s What I Do, begins in Libya where, as it happens, Hetherington’s life was cut short when he died in a mortar blast while covering the Libyan Civil War of 2011 and where Addario was abducted with three fellow journalists while covering the same war.

Trying to capture the perils as well as the satisfaction involved in war photography, the writer describes her experiences of the events in countries terrifically affected by war and disasters, such as Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Sudan and others. She also concentrates on how competition and the desire to get a little more detail - getting a bit closer, just one more shot, just one more sound bite - drive war coverage.

Knowing the grievous consequences of staying a second longer in a war-torn territory does not prevent anyone from not striving for one last image or detail. The writer herself has witnessed near-death experiences while being kidnapped in Iraq and Libya, apart from incidents of mortar blasts and gunshots.

The book also focuses on the complications of being a female in a profession largely dominated by males. Addario exudes doggedness and never surrenders to unfavourable circumstances, probably because of the demands and compulsions of the profession. She visited Afghanistan before the 9/11 attacks and the ‘war on terror’ to photograph the country at a time when it received little attention and when photography of any living thing was strictly prohibited by the Taliban.

With another female journalist, Elizabeth Rubin, the author also covered (as an embedded journalist) Operation Rock Avalanche in the Korangal Valley of Afghanistan, which was launched by US soldiers to root out Taliban fighters and which saw furious fighting.

Without revealing the name, she recounts a New York Times Magazine correspondent, with whom she was expected to meet Gul Agha, an anti-Taliban war-lord, telling her “…as a woman you’re going to ruin our access, so it’s probably best if we do this story separately.” She responds by sitting next to the leader to be profiled when the reporter arrives on the spot. Apart from being sexually groped and choked, she also found that sometimes being a woman in the Muslim world helped to provide smooth access and she took full advantage of it for the sake of her work.

Among the stories of war and suffering, the personal story of the writer as a war photographer struggling to strike a balance in maintaining relationships also features, as she oscillates between hope and despair - “…in this profession, relationships ended in either infidelity or estrangement. A dual life was unsustainable.” The experience of becoming a mother changed her perspective, though, of photography and the way she pictured her subjects.

The narrative in Addario’s book is erratic. At one time, it depicts a disturbing picture of horrifying sufferings. At another, it moves to the life of the author eating, drinking, trekking, swimming, and being with her boyfriend and friends, all of which obscures the thrust of the broader narrative.

Arranged chronologically, the book is an account of a young girl becoming a war photographer and a mother, written in an action-packed style, capable of grabbing the reader from the first page, but leaving them flummoxed in between.

It’s What I Do is also Addario’s answer to the question she was asked all the time - “Why do you do this job?” “…it’s my choice. I choose to live in peace and witness war to experience the worst in people but to remember the beauty.”

Carefully dispersed images of men with guns and children and women in appalling conditions powerfully depict the grief of wars’ victims. But sometimes references to a particular photograph have made and it has not been produced in the book.

(Avneesh Kumar is a doctoral student at the Department of Mass Communication, Aligarh Muslim University)

Such articles are only possible because of your support. Help the Hoot. The Hoot is an independent initiative of the Media Foundation and requires funds for independent media monitoring. Please support us. Every rupee helps.

Subscribe To The Newsletter