An extortion sting implicates Goa's Herald

Over the last few weeks, those of us in the media—and even those with an otherwise peripheral interest in the machinations of the news business beast—have been consumed with the unfolding story of blackmail and extortion by a media group in Goa. On July 14 evening police began a raid of its premises.

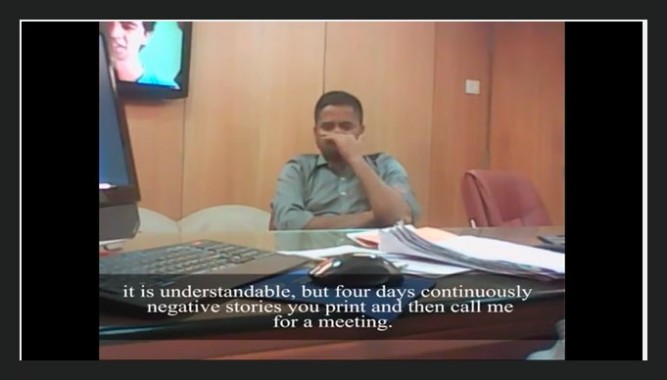

The revelations, rendered all the more intriguing by journalist Mayabhushan Nagvenkar’s serialised release of a video recording, concerns Goa’s boldest and most visible daily, the Herald. Resourceful, dogged and at times even tiresome in his persistence in turning the lens inward, Nagvenkar has this time stumbled upon scorching evidence. The newspaper’s assistant general manager, sales, carrying a message from his bosses tells an offshore casino operator that unless he’s prepared to cough up a substantial amount—Rs 25 lakh per casino per month is the figure heard discussed in the conversation caught on tape—the negative publicity wouldn’t go away.

The sting—carried out obviously by the casino manager/representative sometime last year using a spy camera—has been subtitled and uploaded in seven takes on YouTube by Nagvenkar. The footage speaks for itself:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i2UxMKy7pTg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d2mZr15ZSFo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mNpASILzM50

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gD04nP_9Mdo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XX1xW08V8Bo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zVHGP9seEnY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-_3SLrhs0tg

There are five casinos running offshore in Goa currently. One assumes the nature of their business and the endless controversy surrounding them (more than justified, given the opacity of their operations and the deliberate lack of monitoring coupled with the flip flops on the part of the government), makes them easy game for operators of all kinds.

But what’s of relevance isn’t that the newspaper was negotiating for a huge spike in advertising revenue from a business obviously susceptible to arm twisting. Or that the casino operator found the figure “difficult to digest” (this is too heavy, we can’t get into this kind of extortion, he is heard saying toward the end of the recorded conversation). To those who still believe newspapers are bound by higher ethical standards than most, the shock comes from the readiness to barter editorial independence for a price.

Herald, which still uses its registered Portuguese title O Heraldo, reinvented itself as an English daily in 1983 when the print media in Goa was still in the clutches of a small coterie of privileged mine-owners. Its arrival signalled a major shift in the media business in Goa. Its owner ran a printing press and stationery shop and not an iron ore mine and barges like the rest. An independent voice—perhaps by default—had surfaced when practically none had existed during the Portuguese regime or post-Liberation. Run by a meagre number of media ‘professionals’, the paper became a recruiting and training ground for scores of young journalists—graduates raw off the boat; students still struggling to clear exams; and at times stragglers even, picked off the garden bench outside the office to help tide over the ‘crisis on the desk’.

It was perhaps the anarchy in the functioning of the paper and the cluelessness of its owners that gave the newspaper its flavour and identity in the initial years. Young reporters had space to pursue stories of their own accord, triggering a spate of investigative reportage, something unheard of in Goa till then. Driven partly by the egomania of its first editor Rajan Narayan, the Herald used its heated pro-Konkani crusade in 1986 to endear itself to the Catholic community largely in South Goa. The paper to this day continues to be seen as a ‘Christian’ paper.

While this sworn loyalty from its captive audience has benefited the daily abundantly—its pages are awash with obituaries and ads of Konkani tiatr (theatre)—it has done more harm than good to the Catholic community, which to some extent has come to see the paper as an extension of the often insular preaching from the pulpit.

In 2012 under the editorship of the controversial journalist Sujay Gupta—still editor there—the newspaper ran a blistering campaign against the Congress Party, even exulting editorially later that it had helped steer the ‘Catholic vote’ toward Manohar Parrikar and the BJP in that election. (Gupta tried later to justify this with the argument that “reportage on Parrikar was positive because there was a groundswell of visible support in his favour and we were reporting it”.)

In the current incident with the casinos, his front page editorial to counter the damage caused by the leaked tape seems more like a feeble attempt to distance himself from the dodgy dealings of his own newspaper.

Rumours of paid news involving the Herald is hardly news anymore. The paper’s propensity for hawking its editorial space scaled new highs in the run up to the last general election here. Internal emails exchanged between Gupta and the paper’s general manager Michael Pereira in the time-frame early 2012 and April of that year only underline the extent of the media group’s fall from grace.

To be fair to Herald, it wasn’t the only media organisation in Goa milking the political cow at its most vulnerable and hoodwinking the gullible reader. A coterie of Marathi papers and others were also in on the game. But the Herald, from what several politicians told me at the time, was notches above the competition, fanning out teams to market ‘exclusive’ coverage to candidates—at a price of course. (Nagvenkar’s expose here earned him legal notices from the paper for defamation.) Though Gupta paints himself as the unsuspecting good guy editor in the April 2012 email sent just before he left to start The Goan on Saturday, he was back with the Herald two years later and will, from all indications, be steering the media group to election coverage 2017. Goa’s next general election is due before March next year.

Even by its 2012 reputation, the casino sting has unravelled a new low for the paper. “Shocked and not so shocked at the same time,” was the reaction of a young reporter who had once worked there. Readers who see the media as the last repository of the fight against corruption were stunned and felt far more let down.

But it is the young unsuspecting media trainee and journalists on the job who have most to worry about from the revelations of backroom deals. What if a “hard hitting story” (to use a favourite reference of those running the paper, I should know I did three stints in that newspaper) is turned into more than just a good piece of journalism by those outside the newsroom?

The Herald might be a huge commercial success currently. But it has failed and wounded journalism deeply.