Disastrous coverage

Reprinted from Nepali Times

Given their short attention spans, limited capacity to capture context, and the scripted narrative of international news, reporters cannot be entirely blamed for their unidimensional coverage of disasters. We have seen the pattern repeated after Typhoon Haiyan, Cyclone Nargis and Hurricane Katrina. So, there was a certainpredictability to the way that an earthquake in distant Nepal would be covered.

Anniversaries are a time to revisit disasters, and the story about our earthquake has been written even before the reporters skydive in — government response has been non-existent, survivors are still living in tents, and none of the $4.1 billion pledged last year at a donor conference has been spent. The truth, as we know, is little more complex. But it would be silly to let facts get in the way of a trending topic.

Where was the foreign media and a self-righteous international community when Nepal was reeling under a ruinous Indian blockade, the economic impact of which on the country was much more debilitating than the earthquake? Where were they when the Tarai was burning last August? Was there coverage of earthquake relief material being stuck at the border for five months? Who covered the shortage of aviation fuel and diesel that halted delivery of winterisation kits for earthquake shelters?

And now, when the sky goes dark once more with parachute journalists, the world is fed decontextualised coverage of delays in relief delivery and survivors still not receiving their reconstruction grants. Where were you when patients were dying in November-December 2015 because ambulances had run out of fuel? Didn’t see internationals showing much concern when hospitals ran out of diesel for generators, vaccine cold chains broke down, schools were closed and the country was in the throes of a humanitarian crisis.

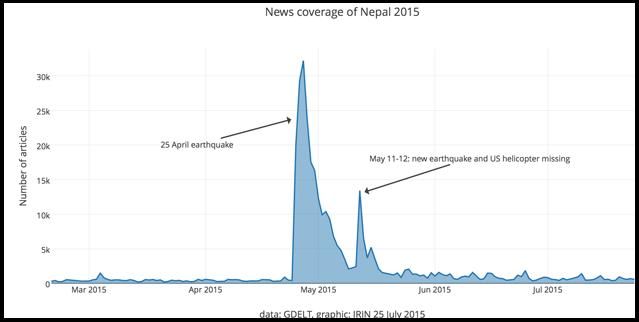

The Google Database of Events Language and Tone (GDELT Project) collaborated with the humanitarian news agency, IRIN to analyse coverage of the earthquake in the first half of 2015, using 300,000 articles in 65 languages that mentioned the word Nepal. Starting with a ‘background radiation’ of an average of 300 mentions per day in March, the number suddenly soars to nearly 33,000 on 25 April (see graph). Then in a week it drops precipitously to 2,000. There is a small peak on 12 May, the day of the 7.3 magnitude aftershock and the disappearance of a US Marines rescue helicopter, and another small blip four days later when the chopper is found in Dolakha.

Illustration: IRIN

Interestingly, the GDELT/IRIN study further analyses the 33,000 mentions of Nepal on 25-26 April 2015 and finds that nearly a quarter of the stories were about the avalanche at Mt Everest Base Camp that killed 16. Even in May 2015, 17 per cent of the stories were still focusing on Mt Everest. Predictably, by mid-May the international media has moved on to disasters elsewhere in the world, and coverage of Nepal falls back to nearly pre-earthquake levels even though the real slow motion disaster was just beginning in Nepal.

The coverage, especially on tv, zoomed in exclusively on the destruction, creating the impression that Kathmandu had been utterly devastated. Monuments had collapsed, and those visuals were just too photogenic to resist. The fact that 90 per cent of the residential buildings in Kathmandu Valley were intact did not seem to register because it did not fit the prevailing news narrative. Reporters are supposed to strive for accuracy, but disproportionate coverage of destruction distorts the truth.

The GDELT Project analysis of the data after May 2015 concludes: ‘…the world’s news media appears to have largely moved on from Nepal, finding it no longer “newsworthy” enough to devote significant attention to.’ If the monitoring had continued, we would likely be seeing a slight rise in mentions of Nepal worldwide now, less steep but peaking perhaps on Monday next week, and a steep descent after that as Nepal and the earthquake once more sink back into oblivion.

This is the reality of international news coverage, and there is little we can do about it. News is a product much like what is called FMCG in advertising parlance — to be gathered, processed, packaged and sold like a fizzy drink or fried drumstick. The market is mainly in the West, and that dictates the selection of what makes news. Earthquakes make it, blockades don’t. It just takes too long to explain.

The Indian blockade was an asymmetrical response to the inability of Nepal’s rulers to address the grievances of plains-dwellers, and its heavy-handed crackdown on ensuing protests last year. It gave the wily Oli government the perfect excuse for the delays in earthquake relief. He whipped up xenophobia and ultra-nationalism, camouflaging his inability to deal with India, to get the National Reconstruction Authority up and running, and to hide the blatant protection of the black-market economy. The Indians did Oli a big favour with the blockade, and allowed him to get away with doing nothing.

In the midst of all this are the bright spots that we feature in the current and previous editions of this newspaper: the communities that have taken up reconstruction on their own, heritage conservationists at the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT) who are rebuilding historic sites with the Department of Archaeology , international organisations like Possible that have forged effective partnerships with the Ministry of Health to rebuild not just destroyed hospitals but also the health system in the earthquake-affected areas, or organizations like Miyamoto International and ChildreachNepal working with the Department of Education to rebuild government schools in Sindhupalchok. These are working examples of non-government organisationsdelivering valuable services by collaborating with government, and not trying to bypass it. Ultimately, our goal should be not to absolve the government of its responsibility but improve its capacity to reach people in need.

News about slow government is no longer news to us Nepalis. It is a given. The news is what we do despite that, but such behind-the-scenes partnerships are just not newsworthy enough for ambulance-chasers.

Kunda Dixit is the publisher of Nepali Times and author of several books, including the trilogy on the conflict in Nepal: A people War, Never Again and People After War.