Why everyone likes a dead journalist in Kashmir

Just like an armed rebel is hero-worshipped once he is killed while fighting government forces in the Kashmir Valley (the slain rebel is hailed as a ‘martyr’), almost everyone in the media fraternity here seems to love a journalist once dead and buried. It’s as if they love to romanticise the dead and glamourise the funeral. When alive, no one seems to care about a journalist. No one seems to bother.

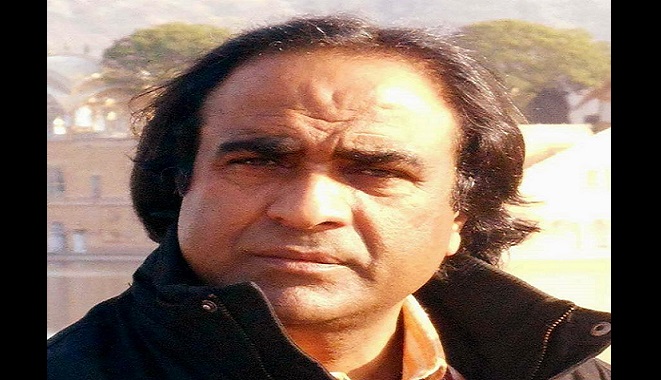

The sudden death of veteran photojournalist, novelist, poet and freelance broadcaster Maqbool Sahil, reportedly due to a cardiac arrest while on his job on 20th March in the Lal Bazar locality of Srinagar has, once again, brought to the fore the same old issues: the culture of work, the newsroom environment, wages, health insurance, provident fund and the job security of journalists working for local newspapers in English and Urdu.

While journalists who work for international media outlets or the television channels and newspapers based in Noida, Delhi, or Mumbai etc have lucrative annual packages, the monthly salary for journalists with Kashmir-based newspapers range from just Rs 6,000 to Rs 30,000.

Something is terribly wrong with the working conditions of journalists in Kashmir.

During a professional career spanning over two decades, no one bothered whether Sahil and his family, comprising his wife and six children, had meals on the dining table, but a spectacle was made out of his lifeless body.

Once his passing away was confirmed, some people began to pay ‘tributes’ to him in such a manner that he was made a butt of ridicule – by talking openly about Sahil’s modest background, it was ensured that everyone in Kashmir knew about his poor financial state. Showing no respect to the sensibilities involved, some also made fervent appeals on social media platforms to collect donations for his family.

Though it was encouraging to see the Kashmir Editors Guild contributing Rs 200,000 to Sahil’s family and to see other attempts made by the newly established Press Club, the Kashmir Working Journalists Association and the Video Journalists Association to help the family, questions remain whether this monetary aid could have been extended to Sahil’s family with more purpose and less noise.

Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti announced Rs 500,000 for the family. The organisation he worked for also stated it publicly that Sahil’s salary would continue until the bereaved family settled down.

In hindsight, all these gestures appear meaningful. But what are the factors responsible for Sahil struggling to make ends meet despite having been a journalist for nearly 20 years? Why did we need to collect money for his family? Why are journalists underpaid despite the fact that most newspapers get substantial government advertisements to sustain their operations?

Who was Sahil?

Sahil, in his early 50s, was known to Kashmir’s media fraternity as a reporter with integrity who was unwilling to bow before the powers that be. On 16 September 2004, he was thrown in jail. He was kept in various jails and interrogation centres for nearly three-and-a-half years.

Five years after his release, in an interview with The Wall Street Journal in 2013, he revealed that “he was deceived by men he trusted”.

“I lost everything,” he told the WSJ. He lost his contacts, his sources, camera, laptop, and his travel documents - even his family home in Arhal Kokarnag in south Kashmir’s Anantnag district, some 100 km from capital Srinagar.

There were reports that he had been tortured in jail. He told the WSJ that “I turned prison into a library”. In his prison memoir ‘Shabistan-e-Wajood’ (The Darkness Inside or The Abode of Existence) written in Urdu, Sahil wrote of being tortured in jail, beaten, suspended by his arms from the ceiling, and having the muscles in his legs battered by rollers.

The army has contested these allegations.

There was not much publicity of his arrest and reported torture in prison. There were no dedicated campaigns for his release by his colleagues, media associations and human rights’ groups either.

At the time of his arrest, he worked for a prominent Urdu weekly “Chattan” (The Rock). According to what Sahil told the WSJ, he was invited to an army base at Badami Bagh Srinagar by the army public relations officer on the pretext of discussing the army placing an advertisement in the newspaper he worked for.

After passing Rajendra Singh Gate of the cantonment, he was thrown into a military jeep by a group of five men in civvies. According to Sahil’s account, he was then blindfolded and taken to the then notorious torture centre Hari Niwas.

Hari Niwas was once the residence of the last Maharaja of Jammu & Kashmir, Hari Singh. Leading human rights defenders allege that Hari Niwas was used by the Indian army as a torture centre between 1997 and 2007.

Sahil was accused of working for Pakistan’s spy agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). He had visited Pakistan in 2001 to interview migrant Kashmiris who had crossed over to the other side of the Line of Control (LoC). He always maintained that all the charges against him were fabricated. The allegations against him were never proved in a court of law.

Before Sahil, another prominent Kashmiri journalist, Iftikhar Gilani, was arrested in 2002 in New Delhi. Gilani, the son-in-law of leading resistance leader Syed Ali Geelani, was kept inside Tihar Jail. Based in New Delhi, Gilani presently works for DNA. At the time of his arrest, he was reporting for the Jammu-based English daily, the Kashmir Times.

He was also beaten and tortured. He was forced to clean excrement with a shirt that he was later made to wear for three consecutive days. Gilani spent eight months in Tihar while Sahil remained imprisoned for nearly four years. Gilani got tremendous support for his release from his journalist colleagues and friends in Delhi - and also from the newspaper that he worked for at the time. In contrast, demands for Sahil’s release, both from his newspaper and the media fraternity, were not forthcoming.

After his release, Sahil started working for the Urdu weekly newspaper Pukaar. He also used to host shows on Doordarshan and Radio Kashmir as a freelance broadcaster. At a later stage, he also joined the Urdu daily Buland Kashmir and the weekly Parcham as senior reporter.

Needless to say, journalism as a profession in Kashmir has made giant strides in the last three decades or so. True, this noble profession has evolved with time. Today, journalists are more skilled, prolific and versatile than before. They also have professional degrees, the necessary training and required skill sets to excel in their areas of specialisation.

The questions, however, remain: Are journalists in Kashmir well paid, too? Are honest and upright journalists being taken seriously by society and, above all, by their employers? Or are most people only interested in milking tragedies, exploiting grief, and making despicable mileage out of the lifeless body of a dead journalist? Why are experienced journalists underpaid in Kashmir? Why do we need to collect donations for someone like Sahil? Do we acknowledge a journalist’s contribution only when he is dead, not when he’s alive? Have we become shroud thieves? Are we merchants of death? Can’t we make a difference by adding life to a scribe’s days with sincerity, and without noise?

To be a journalist in Kashmir is to be prey to violence, suspicion, accused of taking sides and having to think of the consequences of every word. As the anti-India armed rebellion erupted in Kashmir in 1989, many journalists started becoming ‘soft’ targets for the armed forces, paramilitary personnel, policemen, a notorious government-sponsored band of insurgents (renegades), and also the armed rebels fighting for Kashmir’s right to self-determination, independence or those favouring Kashmir’s merger with Pakistan. They have been sitting ducks for all sides.