India 2016-17: The silencing of journalists

Journalist Nagarjuna Reddy assaulted by brother of local MLA Amanchi Krishnamohan and his supporters, February 11, Chirala, AP

May 3rd 2017 is World Press Freedom Day. A HOOT study finds that 54 attacks, and 25 cases of threatening journalists took place in the past 16 months. Though 7 journalists were killed, reasonable evidence of their journalism being the motive for the murder is available only in one case.

Over the last 16 months 54 attacks on journalists in India were reported in the media, according to the Hoot’s compilation. The actual number will certainly be bigger, because last week Minister of State for Home Affairs Hansraj Ahir said during question hour in the Lok Sabha that 142 attacks on journalists took place between 2014-15.

The government will take its own time to disclose the figures for 2015-16. Meanwhile the data reveals a disturbing pattern of impunity. In the 114 incidents of attacks on journalists in 2014, only 32 people were arrested and in relation to the 28 incidents in 2015, 41 people were arrested.

Journalists are increasingly under fire for their reporting. They are killed, attacked, threatened. Barely three days into 2017 came news of the killing of yet another journalist from Bihar. Predictably, the details that followed adhered to the same pattern: a gang of unidentified shooters; motive not known; police suspect a family dispute or a business rivalry, anything but a killing caused by the professional work of the deceased.

In 2016, the deaths of journalists – six in all – made headlines but preliminary police investigations could indicate professional reasons in only three cases.

There were 17 instances in 2016 of threats to journalists – serious cases of death threats, rape threats and intimidation – and two in 2017 till now.

A clear and consistent pattern

The stories behind each of these cases reveal a clear and persistent pattern. Investigative reporting is becoming increasingly dangerous. Journalists who venture out into the field to investigate any story, be it sand mining, stone quarrying, illegal construction, police brutality, medical negligence, an eviction drive, election campaigns, civic administration corruption, are under attack.

Leave alone going out into the field, those who host chat shows in the relative safety of a television studio or voice opinions on social media networks are also subjected to menacing threats, stalking and doxing.

The perpetuators, as the narratives of these cases clearly indicate, are politicians, vigilante groups, police and security forces, lawyers (apart from the Patiala House court incident in Delhi in the wake of the JNU protests, just take a look at the spate of attacks by lawyers in Kerala), jittery Bollywood heroes and, increasingly, mafias or criminal gangs that operate in illegal trades and mining, often under the protection of local politicians and with the knowledge of local law enforcing agencies. Hence, even with clear accusations of the identities of the perpetuators, they get away scot-free.

The data with The Hoot shows that law-makers and law-enforcers are the prime culprits in the attacks and threats on the media. We need to call out the complicity of the political party leaders and politicians’ supporters who beat up journalists, the role of vigilante groups and of emboldened student groups who target journalists and systematically hound them and seek to muzzle them.

The efforts to censor and silence these journalists and writers is relentless, sometimes taking on absurd dimensions. In one case filed against Skoch group chairman Sameer Kochhar for allegedly writing a “misleading” article targeting Aadhaar, the complaint filed by an official of the UIDAI said his actions violated the Aadhaar Act. But according to reports, the FIR has been registered manually as the term ‘Aadhaar Act’ is not updated in their system yet!

Thus far, our focus has been, and quite rightly so, on the brutal killings of journalists. Each death is a permanent silencing of the work of the journalist, the eternal censorship that simply cannot be broken. We have continuously campaigned – as media watchers, journalists’ organisations, editors’ guilds and even the Press Council - about the impunity that shrouds each killing.

Muddying the motives

We have seen family members and immediate colleagues of the deceased valiantly argue that the journalist did indeed die for professional reasons, not due to personal rivalries or disputes or any other non-professional motive that investigating police officers point towards. Often, as in three of the six deaths last year, there are doubts about the motives of the killings.

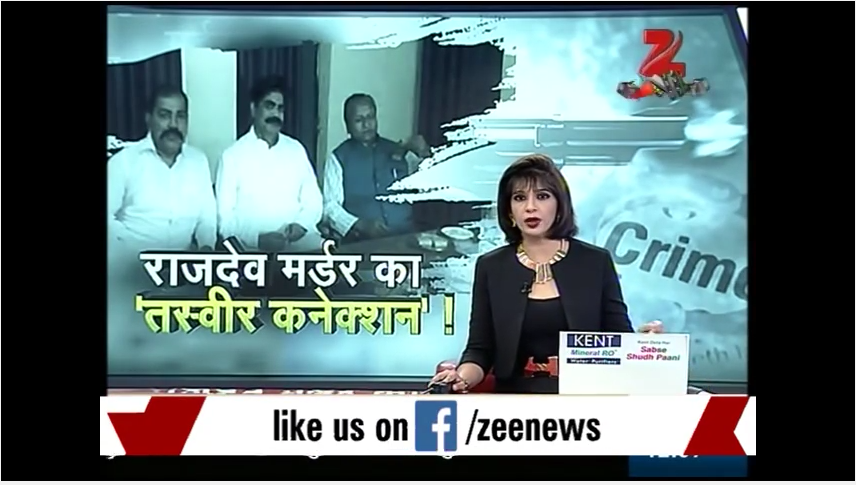

Zee news report on the Rajdeo Ranjan case in Siwan.

But when journalists are threatened or attacked, that does testify that the motive for the targeting was clearly professional. That it is their stories, their investigative work and their bearing witness to all manner of wrongdoings that are under fire.

It is time to examine the threats and the attacks much more seriously than we have thus far. The journalists who have survived gruesome attacks – from immolation bids, acid attacks, strangling attempts and brutal beatings – need to be heard and the perpetrators need to be brought to book. These survivors tell tales and we need to hear them. But do we?

Take a look at this account of an assault in Andhra Pradesh:

Nagarjuna Reddy, a freelance journalist based in Chirala in the district, was assaulted by the brother of local TDP MLA Amanchi Krishnamohan and his supporters over a magazine article and false cases were filed against him. The write up of the journalist highlighted alleged corrupt activities that were undertaken by the MLA. The journalist was thrashed with sticks, other weapons and he cried for help as passer-by watched helplessly. According to News 18 reports, the MLA defended the beating and said, “This is not a goonda raj, he used abusive language. Nagarjuna is not a journalist, he is sudo Naxal (sic).”

That was the report that appeared in the Financial Express. There’s also a video for those who can stomach watching it. The report says only a five-year-old came to the rescue of the journalist. A five year old! What kind of rescue could a five year old have managed?

You would think that, with the obsession we have with violence porn, this video would get some crazy number of views. Till last week, it had garnered only 4291 views. Why didn’t it make more of an impact? Why were we in the media all silent?

Reporting, not being, the news

Perhaps the reason is because journalists hate to be the focus of news, despite the public’s impressions to the contrary, bolstered no doubt by some television anchors who are currently on a huge outreach to promote themselves and their channels. For one thing, drawing undue attention to themselves definitely hampers their news-gathering.

Some journalists, especially those from the electronic media who are increasingly targeted as they are so much more visible with their cameras and other equipment, have taken the beatings as a matter of routine. They curse the police or the mob when they are beaten and their cameras are smashed and then reassemble for the next story, often borrowing equipment from friends.

In the race to feed the beast, some of them are willing to ignore or bypass other beasts. They also know that filing complaints and pursing legal mechanisms to bring culprits to book are time-consuming and dangerous, bringing them more into the spotlight and vulnerable to further targeting. They know the threats and the attacks are a warning that their lives have been spared, this time.

Slow justice or no justice?

Yet, more and more journalists are being forced to file complaints before the police. Last year, an unprecedented number of prominent women journalists had to file complaints about the death and rape threats that they got on social media networks. They are diligently following up on the cases with the police to identify the accused (usually anonymous or using false identities) and get the police to effect arrests.

In other cases, journalists run from pillar to post to get the police to lodge complaints. Take a look at this report from Assam:

14.09.2016, Margherita, Assam: Six journalists went to the Margherita area to gather the facts related to the alleged illegal smuggling of coal from Coal India when they were attacked by more than 40 people suspected to be involved with the coal mafia.

India Today journalist Manoj Dutta was among those assaulted by the mafia men. The journalists alleged that they had to request the Superintendent of Police M J Mahanta for intervention as both the Ledo and Tinsukia police station refused to take any action.

The six journalists were taken to a nearby hospital for treatment.

Why did local police fail in their duty? The journalists were injured, as the picture of the bloodied journalist clearly shows. Why did they have to go from one police station to another just to file a complaint? Why did they get the attention the incident deserved only on approaching a senior officer?

The reasons are hardly a state secret. As the report disclosed, the coal mafia in the area is ‘conducted under the supervision of BJP MLA Bhaskar Sharma's right arm men, Kuldeep Singh and Sandeep Sethia’. Coal worth crores, the report added, is smuggled each night by the mafia from the mines and exported to Punjab, Haryana and Delhi.

The nexus, in almost every case, is there to see. Not merely in cases of corruption and illegal trades, but in the coordinated intimidation between local police and vigilante groups like the Samajik Ekta Manch, which hounded journalist Malini Subramaniam out of Bastar in February last year.

The police, under the guise of investigating her complaint of threats and attacks, intimidated her landlord and neighbours. As her statement said:

“It became clear that in the guise of investigating my complaint, the police was going after those associated with me. The last straw came when my landlord served me an eviction notice on Thursday afternoon. By evening, the Samajik Ekta Manch was staging another protest outside the house of my lawyer….At a time when the nation is outraged about attacks on journalists, one would expect the police to do its utmost to protect citizens and members of the press no matter where they are. Instead of offering this protection, the Jagdalpur police has contributed to a situation where I was so fearful that I felt compelled to uproot my family and leave my home”.

Leave or die. The options are limited. In both situations, justice is still elusive. In cases of deaths of journalists, it is the pain-staking efforts by family members that push the case forward. On May 14 last year, the killing of Rajdeo Ranjan shook the media and the administration in Bihar. Ranjan was a well-known journalist of Siwan and the needle of suspicion pointed to the jailed RJD MP Mohammad Shahabuddin.

Amidst intense political pressure and media scrutiny, besides petitions to the Supreme Court by the wife of the deceased, the case was handed over to the CBI for investigation and the accused arrested and put behind bars.

While justice takes years and the process itself is punishing, media scrutiny helps. Last year, the trial in the murder of Mumbai journalist J. Dey began and there was some progress in the investigation of the death of journalist Umesh Rajput with the arrest of two persons. But there’s little detail and even less media attention over the CBI’s closure report on the suspicious circumstances surrounding the sudden death of Aaj Taj journalist Akshay Singh who was covering the Vyapam scam.

Can the law fix impunity?

Interestingly, even as Minister Ahir told the Lok Sabha that ‘existing laws are adequate for protection of citizens, including journalists’, the Maharashtra government acceded to the demands of a journalists’ organization, the Patrakar Halla Virodhi Samiti, to pass a law making attacks on journalists and the destruction of property of media persons and media houses a cognizable offence.

Will this help? The jury’s still out on this but if the focus returns to relentless follow ups in each case at the ground level, the strengthening of journalists’ and their working conditions at the professional level, more networking with media rights organisations and more baring of teeth by bodies like the Press Council, the Editors’ Guild and the News Broadcasters Association, perhaps we’ll get there.

Details of attacks and threats