Thin line between free and seditious speech?

It is hardly surprising that the Maharashtra government’s guidelines to its police officers on applying charges for sedition betray its anxiety over public criticism of government action,but can its circular set aside the decision of the Supreme Court of India?

As it is, the Devendra Phadnavis government is quite touchy about criticism. Remember the angry tweet threatening defamation because of reports of a flight to the US being delayed? Or socialite and writer Shobha De who got a privilege motion for a tweet criticising the move to screen Marathi films in multiplexes?

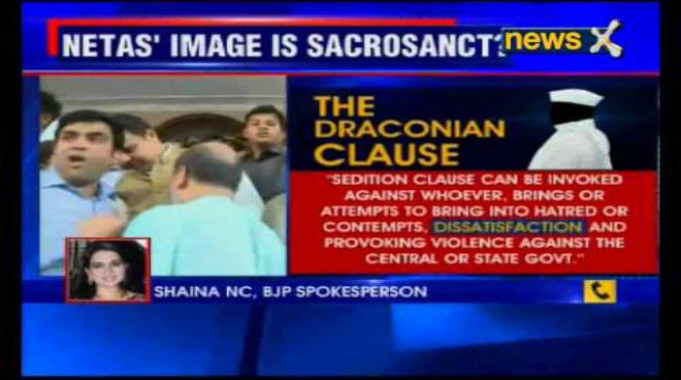

The guidelines, issued in a circular dated August 27 to the police, come in the wake of the case against cartoonist Aseem Trivedi. The guidelines state that sedition charges, under Sec 124 A of the Indian Penal Code, would apply to whoever is critical of the central and state governments, elected representatives belonging to the government, Zila Parishad chairmen, Mayor of a city, and other elected representatives of the government.

A number of judgements have made a distinction between the criticism leveled against the state and against the government and its officers and some judgements by high courts of different states have even held sedition to be unconstitutional. The Supreme Court, in the Kedar Nath case, however, upheld the constitutionality of sedition. But the court said that there was a distinction between “the Government established at law” and “persons for the time being engaged in carrying on the administration.”

In his order in the Aseem Trivedi case, Justice J M Jamdar of the Bombay High Court clearly stated that charges of sedition ‘aims at rendering penal only such activities as would be intended, or have a tendency, to create disorder or disturbance of public peace by resort to violence’.

The order went on to state that 'A citizen has a right to say or write whatever he likes about the Government, or its measures, by way of criticism or comments, so long as he does not incite people to violence against the Government established by law or with the intention of creating public disorder'.

On this basis, the court had suggested that the state Home Department issue guidelines to the police, in the form of pre-conditions to the invoking of Sec 124 A. Thus, sedition would apply only if words, signs or representations that brings the Government (Central or State) into hatred or contempt or cause or attempt to cause disaffection, enmity or disloyalty to the Government are used, and these ‘must also be an incitement to violence or must be intended or tend to create public disorder or a reasonable apprehension of public disorder’(emphasis mine).

The guidelines, the court suggested, must make it clear that commentsexpressing disapproval or criticism of the Government with a view to obtaining a change of government by lawful means without any of the above (emphasis mine)are not seditiousunder Section 124A.

Besides, obscenity or vulgarity by itself should not be a factor for deciding whether a case falls within the purview of Section 124A of IPC, for they are covered under other sections of law.

In addition, for invoking sedition, a legal opinion in writing, which gives reasons addressing these pre-conditions, must be obtained from Law Officer of the District followed within two weeks by a legal opinion in writing from Public Prosecutor of the State.

Clearly, the circular departs from the court’s order and brings in elected representatives and government officers in the ambit of sedition. Criticism against these officers will also constitute sedition, the circular states.

The circular also does not pay attention to the court’s clear statement that a clear and present danger to public order or incitement to violence must be part of the comments or words that are considered seditious.

Advocate Mihir Desai, who had intervened on behalf of AseemTrivedi in the petition filed by social worker Sanskar Marathe, told The Hoot that “the circular does not reflect what the court ordered”. The circular would have to be examined more closely to determine its implications. In any case, all the five points laid down in the circular will have to be satisfied in conjunction, he added,. The circular was unclear and should be challenged, he felt.

Sedition, which attracts punishment ranging from three years to life imprisonment, is a throwback of India’s colonial laws, and has been increasingly used lately against dissenters, including Dr Binayak Sen, editors Seema Azad and Vishwavijay of ‘Dastak’ magazine, and more 7000 villagers protesting the nuclear power plant in Koodankulum, Tamil Nadu. Mahatma Gandhi, who was charged with sedition, described it as the ‘the prince among the political sections of the Indian Penal Code designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen’.

There has always been a strong demand to drop sedition from the statute books. Several countries of the Commonwealth, including India, continue to hold on to sedition even as the UK decided to drop it in 2009, from their own common law after a concerted campaign from free speech groups. In India, the campaign against the arrest of Dr Binayak Sen prompted the then Union law minister Veerappa Moily to agree that sedition laws were outdated.

But why do governments want to hold onto sedition? Given the convenience of this law and its sweeping applicability, the answer is quite a no-brainer. In the course of the hearing in the Aseem Trivedi case, Maharashtra’s Advocate General Sunil Manohar said that a senior police officer should decide whether to make an arrest in such cases or not. He also argued that ‘time should not be wasted in seeking legal opinion and a senior police officer should be entrusted with the responsibility of taking the decision on arrest’.

Manohar, according to reports on the hearing, pointed out there was a “very thin line” between where the freedom of speech ends and an offence of sedition is made out.

It is the contours of this thin line that the Maharashtra government wants to change, drawing it more widely to restrict more speech.