‘Where is Prageeth?’

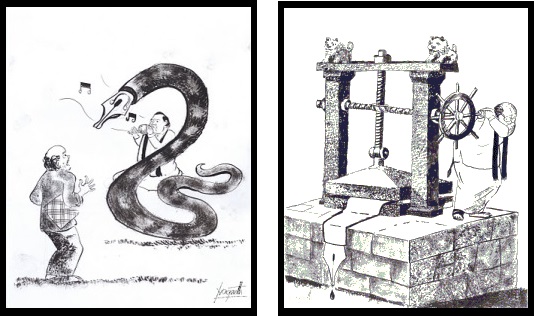

It began like any other day for the Eknaligoda family in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Political cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda left for the Lanka eNewsoffice on January 24, 2010. He never returned. He is said to have left the office for a meeting after a mysterious phone call, but did not reach home, and has not been heard from since.

Eknaligoda had been at the receiving end of death threats and had even told his wife that he was on a hit list. When he disappeared, it was about nine months after the end of Sri Lanka’s long civil war, and he was reportedly investigating the alleged use of chemical weapons by the Sri Lankan army against the Tamil civilian population.

Also significant was the fact that Eknaligoda had disappeared two days before the presidential elections in which he was campaigning for Sarath Fonseka who was standing against incumbent President Mahinda Rajapakse. Eknaligoda’s investigation into corruption and nepotism under the Rajapakse regime was on an USB drive that his wife Sandya says went missing along with him.

The wave of Sinhala nationalism on which Rajapakse rode to victory also threw cold water on the investigation into Eknaligoda’s disappearance. “When I first reported my husband’s disappearance to the police, they scoffed and said it was ‘fashionable’ for journalists to be abducted, and that Prageeth would soon show up. They told me to go home and wait,” says Sandya.

Her search was not only mocked but actively stonewalled. The case hardly saw any forward movement despite innumerable trips to the police station, courts and other authorities. In a blatant attempt to derail the investigation, in 2011, Mohan Peiris, the former attorney general, told the UN Committee Against Torture that Eknaligoda had not been abducted or disappeared but had fled the country and sought asylum overseas.

Challenged later in court over this misleading claim, Peiris claimed that his memory was weak and that he did not remember the source of that (mis)information.

Sandya persevered and her relentless search for accountability took her eventually to the media and the United Nations. Following many statements by local and international organisations, protests, vigils and sit-ins, a few facts began to trickle out. However, it was only under the new government of Maithripala Sirisena in 2015 that a fresh investigation was launched and the role of the army – which Sandya had long suspected – came to be established.

Over a period of time, nine suspects, including four members of the Army Intelligence Unit, were arrested. Most are now out on bail, leading to apprehensions that the investigation could be tampered with.

In addition to shouldering the responsibilities of caring for her two children, Sandya has borne the brunt of the retaliation that has accompanied her pursuit of the truth. At a court hearing in Homagama, Colombo in January 2016, prominent monk Galagodatte Gnanasara, head of the Sinhala nationalist Bodu Bala Sena (Buddhist Power Force) openly threatened her. In a grandiose gesture of ‘nationalism’, he offered to exchange places with the military personnel taken into custody over Eknaligoda’s disappearance.

“He was shouting and accusing me of demoralising the army by publicising my husband’s investigation into the alleged use of chemical weapons. I have even been called an LTTE supporter,” says Sandya.

In January 2017, the Criminal Investigations Department (CID) concluded that Eknaligoda had been held in Colombo after being abducted in Bataramulla area of Colombo and then taken to an army intelligence camp at Giritale in Polonnaruwa district.

There are wider ramifications to the case. Getting to the bottom of Eknaligoda’s disappearance can strengthen the fight to end impunity, which did not end with the war. The International Movement Against All Forms of Discrimination and Racism, a non-governmental organization in special consultative status with the United Nations, made a statement to the 36th Session of the UN Human Rights Council in September 2017 titled “Enforced Disappearances in Sri Lanka”.

“Enforced disappearances have been used to subdue political dissent and counter terrorist activities, both during and after the armed conflict....In 2016 at least ten cases were reported between March 30th and June 30th. The most recent Commission of Inquiry received around 21,000 complaints and the Government stated that they have received over 65,000 since 1994.”

In recognition of the continuing phenomenon of enforced disappearances, the government ratified the International Convention to Protect All Persons from Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances in 2016 and introduced the Enforced Disappearances Bill in Parliament in March 2017. The Bill, which does not have retrospective effect, has come in for criticism from opposition parties, but has been hailed by Sri Lanka’s Human Rights Commission as a step in the right direction to fight impunity.

The President gazetted the Office on Missing Persons in July 2017 - the first independent and permanent mechanism to address missing persons and the issue of enforced disappearances. The office will be closely watched to see if even a single one of Sri Lanka’s missing thousands is traced.

The administration for its part, claims to be progressing with investigations. At the UNESCO conference on December 4, 2017, marking the International Day to End Impunity of Crimes against Journalists, Sri Lanka’s Police Spokesman ASP Ruwan Gunasekara said that the investigations by the CID were underway. “As Sri Lanka Police, we are committed to, and we have strict orders to conduct in-depth investigations and bring culprits into book. We will not rest until we achieve this goal,” he said.

Sandya, like all the families of disappeared persons, will be waiting and watching. In recognition of her perseverance on behalf of the disappeared persons of Sri Lanka, she was conferred the International Women of Courage Award in 2017.

She is the embodiment of quiet determination, her transformation from housewife to an ardent champion of human rights evident in her remarkable pursuit of justice and accountability in Sri Lanka. “Every action counts. Every postcard, every poster, every slogan and every media report makes a difference. Never allow the campaign for the disappeared to disappear.”

Laxmi Murthy is a journalist based in Bangalore.