Barefoot Journalists

The Fellows visiting villages.

One of the most important indicators of the social relevance of the media is the extent to which the problems of the weakest communities find expression. If this happens to be inadequate, is it possible to correct the imbalance? Perhaps by training people in the marginalized community to bombard the local media with news and press releases about what is on their mind?

This experiment was taken up in the context of the Sahariya tribals and other weak and vulnerable groups of Baran district (in Hadauti, Rajasthan) by a small project based on creating a media contact centre called the Hadauti Media Sandarbh Kendra (HMSK).

The project was supported by the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust and implemented by the Jaipur-based Vividha Aalekhan Evam Sandarbh Kendra (generally known as just Vividha), a media resource centre specializing in issues relating to women and the weaker sections of society.

Vividha co-ordinator, Mamta Jaitly says: “ Sankalp was in the middle of several highly promising activities like the rehabilitation of bonded workers which had a lot of potential for helping the Sahariyas but were opposed strongly by vested interests. In such a situation it was very important for the voice of the Sahariyas to be heard but their viewpoint had hardly ever appeared in the media. It was in this context that the need for a project aimed at increasing and improving the coverage of issues important for Sahariyas and other weaker sections was strongly felt.”

A small media centre was created. Its co-ordinators kept the media informed about the views of the Sahariyas through press releases. The centre also trained 20 local persons over three years on how to prepare a good press release and send it to newspapers and media outlets in the area.

“This led to much improved and frequent coverage of problems faced by the Sahariyas. In some cases, long overdue NREGA payments were made after media coverage based on our press releases while in other cases, problems relating to the public distribution system were sorted out,’ says Firoze Khan, HMSK co-ordinator.

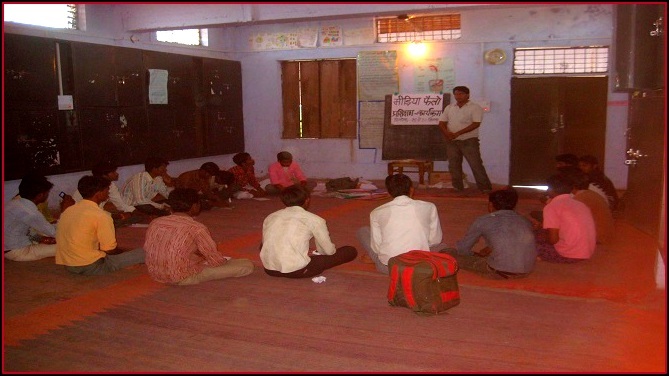

Training of jan patrakars at the centre

A recent review report on the project confirms these achievements. From October 2009 for three years, 1,360 press notes and news items were released by the HMSK to local newspapers, an average of slightly over one per day. Out of these, 823 news items were published, often in more than one outlet.

After the end of the formal project period, the effort continued but on a lower scale. From early 2014 to September 2015, 250 press notes and news items were released and197 were published. A single dedicated media person (called jan patrakar or barefoot journalist), Manoj Rathore, wrote 148 press releases and news items in one year.

The issues covered in these press releases were land rights, bonded labour, rural employment guarantee or NREGA work, the public distribution system, housing schemes and other welfare projects, social reform issues such as child marriage and sex ratios, the problems of women, health problems including silicosis disease, adverse weather conditions, special surveys and fact finding reports. Apart from covering Sahariyas, the press releases also covered dalits and other weak communities.

A particularly encouraging aspect of this project was that the HMSK and its barefoot journalists made a point of following up issues with the relevant officials and re-visiting the problem after some time to see if remedial action had been taken. As a result, remedial action was taken by the administration in several cases:

- In Lakrai village, for example, about 40 bighas of land belonging to tribals was unjustly taken over by the forest department. After press releases on this drew the media’s attention, the land was restored to the wronged tribal families.

- In Kishanganj and Shahbad blocks when rationed grain was not distributed for one month, media reports led to speedy remedial action.

- In some villages, released bonded workers were denied access to clean drinking water but when this problem was highlighted in the media, the administration quickly arranged water tankers.

- In other cases, very poor people who had become victims of accidents or natural disasters like lightning were able to get compensation from the government.

- Installments of housing schemes had been delayed, resulting in half-finished houses but when this issue was published prominently in the media, the remaining instalments were also provided.

Some of these successes were possible owing to the tremendous support provided to the project by a local voluntary organization, Sankalp, which is known for its deep commitment to the welfare and rights of the Sahariyas. Its co-ordinator Moti (he always uses this short name) had a very good understanding of the potential of media coverage and was keen to experiment with the idea of barefoot journalists from within the weaker sections in rural areas.

It was due to Moti’s support that the project could continue to some extent even after the funds stopped after the completion of the designated three years.

Moti’s sudden death at a young age was catastrophic for all the activities relating to the welfare of the Sahariyas in this area. Many activists, particularly Sahariya women activists for whom he was a mentor, were shattered. His death also had a very adverse impact on the media project, although efforts are still being made to continue it to some extent.

But what remains indisputable is that, at its peak, this project played a very important role in improving media coverage of the Sahariyas substantially and this in turn helped to solve many of their problems.

Bharat Dogra is a freelance journalist who has been involved in several social movements and initiatives. Nearly 8000 of his reports and articles have been published in India and abroad during the last 44 years.