Facebook: Opening the gates to the Web or closing them?

About a month ago, on December 9, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) released a new consultation paper, on the regulation of “differential pricing” charged by Telecom Service Providers (TSPs) for data usage, for public comments. This was the second round of public consultation by TRAI over data related services offered by TSPs. The second round was prompted by widespread criticism of zero-rating services, such as Free Basics by the Facebook-Reliance consortium and Airtel-Zero by Bharti Airtel.

The open period for filing of public comments and rebuttals ended on January 7 and TRAI is expected to announce its verdict on regulating zero-rating data services by the end of January.

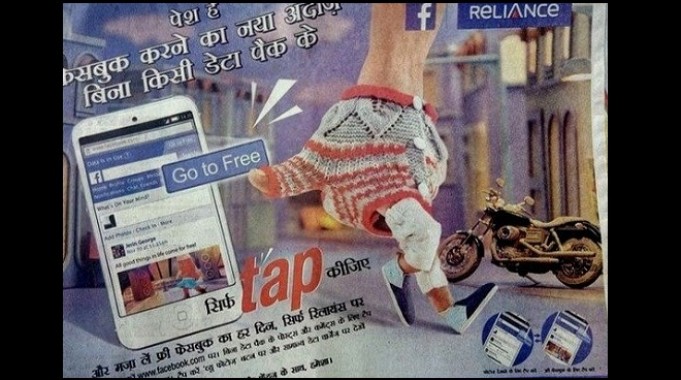

To bridge the digital divide and get more users, Facebook has launched Free Basics in 36 countries, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and the Maldives in South Asia, in partnership with local mobile phone companies. In India, Free Basics was launched in partnership with Reliance Communication, one of the major players in the mobile telecom business in the country.

The Free Basics application can be downloaded on a smartphone or any mobile device. It allows a user to visit a selection of empanelled websites on the Internet “for free without data charges, and include content on things like news, employment, health, education and local information.”

For the moment, TRAI has suspended Free Basics and other similar services because prima facie it appears to violate established pricing rules under the Telecom Tariff Order (TTO). The current TRAI regulation on tariffs mandates that any differential pricing, including zero-rating, must be non-discriminating, transparent, not anti-competitive, non-predatory, non-ambiguous and not misleading.

Many activists, technologists, developers, and people from the startup community argue that the manner in which zero-rating services have been set up breach the foundational principle of Net Neutrality on the Internet. The Net Neutrality principle prohibits blocking or slowing down content by differentiating among websites in any differential pricing plan for data usage.

Some have pointed out that the prefix “free” is misleading because like everything else in the sharing economy of the Internet, Free Basics is not actually free. However, this line of criticism is mostly philosophical because we know that there are free services on the Internet. All of us have entered into such a Faustian bargain with our free emails, social networking accounts and free messaging services such as What’sApp and Viber. All the seemingly free services on the Internet that we have come to depend on collect user data, which is then monetized through targeted advertising and other means.

The central issue in the public debate during the open comment period was the tension between the digital divide and Net Neutrality. The debate was vigorous and occasionally even disparaging towards the opposing sides. In such a climate, the TRAI will find it really hard to come up with a win-win solution that will be acceptable to Net Neutrality advocates and those who want Internet access extended to almost 70 percent of Indians who currently don’t have it.

It is a fact that in the new digital economy, the majority of Indians are being disadvantaged by the digital divide and are losing out to competition. Additionally, without near universal access to the Internet, the public policy tilt in favor of the digitization of government services and growing e-commerce will only further exacerbate the gulf between the haves and the have-nots.

Indeed, there are alternative models that stay clear from violating Net Neutrality such as free Internet access in community libraries in the West, free Wi-Fi in urban public spaces, subsidized connectivity in rural and underserved areas, and free modest size data package from Internet Service Providers (ISPs) in lieu of watching advertisements and the collection of user data by the providers.

Then there is a model that has not been talked about a lot in India: it involves imposing a cess on TSPs that can be used to create a universal service fund. The government can use this fund to subsidize a small monthly data package, say of about 500 MB, which can be offered to people who do not have the means.

However, a problem unique to countries such as India with huge disparities among the haves and have-nots is that the basic infrastructure isn’t there for most community and subsidy models. Moreover, most alternative models fall short when it comes to providing universal and efficient services on mobile devices.

To supporters, zero-rating services like Free Basics on ubiquitous mobile phones, are a quick solution to the growing digital divide. To critics, it is a Faustian bargain in which, for the sake of universal access and bridging the digital divide, we are being asked to ignore the violation of the Net Neutrality principle that for many is the soul of the Internet.

Dominant gatekeepers

Besides, this may also make a few telecom and tech companies gatekeepers of all information. A few dominant gatekeepers will have the power to select a very small selection of websites from a highly diverse and pluralistic information ecosystem. This could have a negative impact on the political economy, the free market and even on democracy.

The pushback from critics against an earlier iteration of zero-rating under the internet.org web portal forced Facebook to tweak it with the Free Basics app, which seemingly gets around the egregious violation of the cardinal principle of Net Neutrality by offering its platform, in principle, to any website that would want to join it. In India, the Free Basics app at the time of writing this article had about 30 websites empanelled for zero-rating in the approved list.

Zuckerberg in a column urged the public in India to support Free Basics because Facebook had addressed the “legitimate concerns” raised earlier during the internet.org public debate. Implicitly, it seems that he was suggesting that Free Basics is not only a name change from internet.org. He argued, “Instead of welcoming Free Basics as an open platform that will partner with any telco, and allows any developer to offer services to people for free, they claim – falsely – that this will give people less choice. Instead of recognizing that Free Basics fully respects net neutrality, they claim – falsely – the exact opposite.”

Zuckerberg and his supporters have argued that a user can still choose to access the Internet without any content/website restriction using the usual web browser on her device. Evidence from other countries is that, in fact, many users after experiencing the benefits of limited free access to Internet do choose to opt for a regular access outside the zero-rating wall of Free Basics.

This most likely may happen with most zero-rating services in India too. Once people get on the Internet, in a very basic way for email and social media, they see other benefits too in education, health, and commerce.

Technically speaking, Zuckerberg may be right, but Facebook with its Free Basics is not doing enough to mitigate the concerns on net neutrality. However, the fact is that until now, in India, only about 30 websites have been empanelled on Free Basics. This only supports the argument that Free Basics will further enhance and consolidate the gatekeeping power of Facebook, which has been growing over the years, as more and more people say they get their news and information from the Facebook feeds.

So there are some pertinent questions that Facebook must answer - because the related issues are still shrouded in ambiguity and secrecy - before TRAI allows Free Basics to chip away at the principle of Net Neutrality for the sake of bridging the digital divide in India.

Surely, there must be technical considerations for a website to get on the free list yet why such a small number of websites? What qualifies a website to be empanelled? What must a website give to Facebook-Reliance to get on the list of approved websites for zero-rating? Is there a cap on the list of empanelled websites or will the list for all practical purposes be unlimited? And finally, what guarantees have Facebook-Reliance offered on the issue of data security to online companies, developers and consumers?

(Anup Kumar teaches communication at the School of Communication at Cleveland State University, Ohio).