Kashmir cut off: why internet bans are bad for democracy

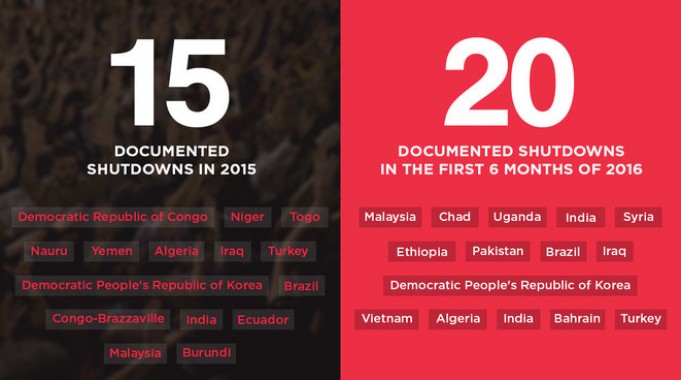

Pix : India is in the company of countries not known for their free expression record.

When angry protests broke out after security forces shot dead charismatic Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani on July 8, the Jammu and Kashmir government promptly blocked mobile internet services in the region. The move, as always, was apparently to prevent the spread of dangerous rumours and incitement to violence through social media. Twelve days later, large swathes of Kashmir — the Valley as well as the Jammu region — continue to be cut off from the internet. Violence was not prevented, though — police firing has claimed 43 civilian lives so far. What has been prevented is people’s access to information and their right to free speech.

The internet shutdown in Kashmir is the latest example of the rising incidence of internet blocks in the country. According to a report on internet shutdowns in India prepared by the Centre for Communication Governance, National Law University, Delhi, from January 2015 there have been 28 instances of internet blocks in the country. Of these, as many as 14 have taken place this year. The sharp spike in the number of bans becomes doubly evident when you consider that there were just seven instances of internet curbs between 2012 and 2014.

So why are we witnessing this sudden upsurge in internet shutdowns? And why is it a matter of grave concern?

Of course, in each case the state government’s action was prompted by its apprehension that untrammelled access to the internet in general, and social media in particular, would result in the spread of rumours and people posting inflammatory messages, thereby exacerbating an already volatile situation. Since nearly 94% of India’s 332 million internet subscribers access the Net through their mobile handsets, the axe falls chiefly on mobile internet services, while broadband is left mostly unaffected.

There are two serious problems with state governments’ knee-jerk reaction of throttling the internet to deal with law and order issues. First: internet shutdowns violate citizens’ right to freedom of speech and expression and are inherently damaging to democratic institutions. And the growing impunity with which state governments are pressing the internet kill switch suggests an equally growing disregard for the sanctity of these rights. Incidentally, a United Nations Human Rights Council resolution passed earlier this month condemns internet censorship and terms it a violation of international human rights.

Second: A blanket ban on the internet may not necessarily stanch dangerous rumour mongering in a situation of civil unrest. On the contrary, it is easier to spread fear and rumour amongst people cut off from the world, cut off from online platforms that could be used to disseminate reliable information and allay fears. Add to this the collateral damage of citizens unable to access online financial services, including something as basic as ATM services, and the loss of crores by way of commerce, and the essential wrong-headedness of internet blackouts begins to sink in.

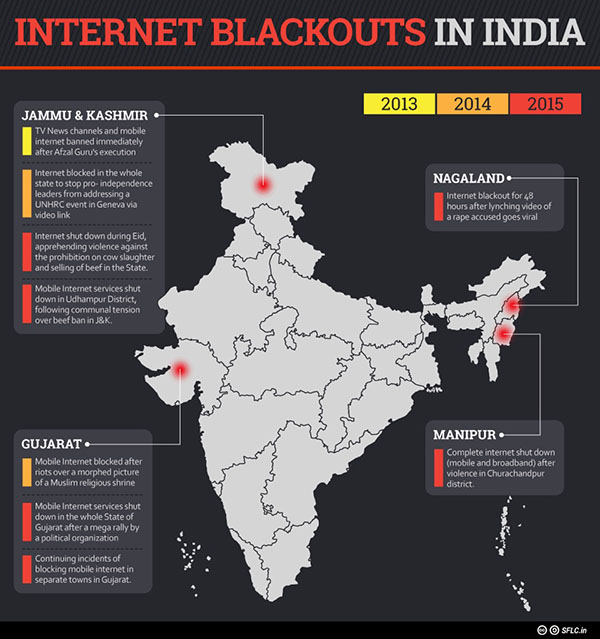

Consider the rash of internet shutdowns in India in recent months. The Gujarat government blocked mobile internet services in parts of the state five times in 2015 during the Hardik Patel-led Patidar agitation for reservations. It followed that up with two more instances of internet shutdowns in February and April this year — the former for as trivial a reason as to prevent cheating during a revenue recruitment service exam. This year, the Haryana government issued orders to ban mobile internet twice during the Jat agitation for quotas. Apart from the current ban, Jammu and Kashmir has put internet curbs four times already this year. Rajasthan has witnessed four incidents of internet ban in the last 18 months. Shutdowns have taken place in Jharkhand, Nagaland, Manipur, Meghalaya and Uttar Pradesh as well.

Infographic: Software Freedom Law Centre, India

Most internet blocks in India take place under Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), 1973, which gives the state government the power to stop unlawful assemblies of people to prevent public disorder, rioting and so on. It can be brought into force by a notification signed by the district magistrate or a commissioner of police in a metropolitan area. However, legal experts have been arguing against the constitutional validity of imposing internet shutdowns, especially under Section 144 of the CrPC.

One argument is that Section 144 does not even contain the appropriate legal power to order a suspension of Internet services, since the power to regulate telegraphs (or the internet in this case) is vested with the Union and not with the state. In that context, any internet shutdown should really take place under Section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act and Section 69A of the Information Technology Act. (The former empowers the Union government to intercept or prevent the transmission of messages under certain circumstances and the latter refers to the blocking of specific websites.)

In September 2015, soon after Gujarat was hit with a week-long disruption of mobile internet services during the Patel reservation stir, a PIL was filed in the Gujarat High Court challenging the constitutional validity of imposing blanket bans on the internet under Section 144 of the CrPC. The petitioner, a law student named Gaurav Sureshbhai Vyas, argued that internet blocks were excessive, arbitrary, and violative of citizens’ fundamental rights. But the high court rejected the plea and upheld the state government’s decision to ban mobile internet services as “just and proper”.

Thereafter, Apar Gupta, lawyer and internet freedom activist, filed a writ petition against the Gujarat Hight Court judgement in the Supreme Court. However, in February 2016, the apex court too dismissed the petition and upheld the power of state and district authorities to impose bans on the internet in the interest of preserving law and order.

Obviously, the concerns regarding public safety and security are legitimate — which accounts for the courts’ almost reflexive rejection of any plea to rule internet shutdowns as unconstitutional. “It is easy to argue that you should not shut down the internet to check copying at exams,” says Chinmayi Arun, executive director, Centre for Communication Governance, National Law University, Delhi. “What’s more difficult to argue is when there are countervailing priorities, such as clear incitement to violence. But then you need to ask, does the government need to shut down the whole internet? Can you do it any other way?”

In 2012 there was a deluge of misinformation circulating about people from the northeast, leading to their exodus from places like Bangalore and Pune. At the time, the government had only blocked bulk SMS services to prevent the dissemination of inflammatory SMSs and MMSs. In 2013, a two-year-old morphed video uploaded on YouTube was said to have sparked the Muzaffarnagar riots. But that did not provoke a blanket ban on the internet either.

So if there is an apprehension of proximate harm from virulent social media messaging, should the government only do targeted blackouts of websites or apps? Unfortunately, that doesn’t work because it is impossible to restrict access to specific apps such as Facebook, Twitter and so on at a localised, micro level. And you can’t very well shut them down throughout the country because one state is simmering with tension.

In this context, it is worth noting that during the riots in the UK in 2011, the British government did consider putting curbs on social media being used by rioters to foment trouble. But eventually, better sense prevailed. As then Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg said, “There is not going to be a Chinese-style blackout…And let’s not forget that social media was very helpful to lots of people in bringing communities together.” In fact, subsequently, there have been a number of scholarly studies and social simulation experiments to show that restricting social media in times of unrest actually leads to greater violence.

India is not the only country that hits the internet kill switch at regular intervals. According to AccessNow, a global advocacy body for digital rights, in the first six months of 2016 alone there were 20 instances of internet blocks in as many as 14 countries, including Brazil, Pakistan, Vietnam, Chad, Uganda, Bahrain and so on. Turkey too suspended internet services after the blast in Istanbul airport in June and also in the wake of the attempted coup last week.

India, which is labelled “partly free” by the Freedom on the Net Report, 2015, should not, however, take comfort in being part of this dubious group of countries that throttle the internet with impunity. For curbs on the internet, and hence the right to freedom of speech and information, are so fundamentally at odds with democratic principles that it should only be imposed in the rarest of rare circumstances.

India’s courts could have acted as a discretionary brake on internet blocks. Unfortunately, activists point out that the judiciary — and that includes the district magistrates who sign the order for internet bans — are woefully out of sync with the age of the internet economy and hence unable to exercise that much-needed discretion. “They are mostly elderly and cannot grasp the effects of a mobile internet shutdown,” says Manan Bhatt, advocate-on-record, in the Gaurav Sureshbhai Vyas vs State of Gujarat PIL case. “Besides they themselves are mostly unaffected since broadband services may be on. Even a lot of NGOs say, ‘So what if there’s no internet and social media for a few days? It’s like a fast! What’s the harm if it prevents violence?’ ”

Evidently, lack of awareness is a problem, as is a lack of appreciation of the fact that muzzling the internet at every hint of trouble is more in tune with paranoid dictatorships than with a vibrant democracy whose government touts “Digital India” as an article of faith. “Anything that affects free speech to this degree should ideally be avoided,” says Chinmayi Arun. “At the very least, it should be done with clear safeguards so the government is not able to abuse the power.”

India is a long way from building those safeguards into laws that may be invoked for internet shutdowns. For that to happen, the conversation around it needs to begin. As Jammu and Kashmir continues to remain behind the iron curtain of an internet lockdown, now is a good time to start that conversation.

Shuma Raha is a senior journalist based in Delhi