The Nation Wants to Know! But which Nation?

On May 15, a day ahead of the 2014 Election results announcement, Times Now ran a promo of its next day’s coverage. Before the channel cut into the promo, it ran a short brag, filled with neatly placed graphics. No matter who won or lost the next day, the channel wanted the world to know that they had won their race. The short introduction to the channel’s advertisement for itself intended to announce the channel as the Numero-Uno, something that is built into its DNA. What followed revealed much more.

The news anchor cut into a video having announced, “India’s number one channel has once again broken all records on social media with the maximum Twitter buzz. Your Channel’s hashtags have generated the maximum “potential impressions” leaving the competition far behind.” The anchor/model/marketing executive in the advertisement video stood in front of a graphic, crowning @TimesNow as the fastest growing newsfeed and gave a tally of the 1,51,16,040 “potential impressions” that Times Now had made online with its hashtag #MegaExitPoll- the kind of number Times Now liked to brag about. He also referred to “Twitter impressions” - the term is twitterlingo for the reach of a post. The appearance of the term on a news channel to prove its effectiveness should make one wary. It is a reinvented version of an equivalent term from the erstwhile print era - media impression.

Not so long ago, the Return on Investment (ROI) of a public relations campaign used to be measured using media impressions. The media impression of an advertisement in the daily newspaper was obtained by multiplying the circulation with the presumed readership. For television and radio, media impressions referred simply to the audience that watched or listened to a show as computed by a rating agency.

With online usage becoming more widespread, today it is big data analysers, using Twitter and Facebook feeds, hashtag campaigns, and artificial intelligence, that calculate impressions. Though the term has undergone a slight change and become potential impressionor Twitter impression, the method of calculation has, in principle, remained the same. Impressions, broadly defined, refer to any interaction of a piece of content with an audience member.It is a term of significance for advertisers looking to reach the maximum number of consumers.

But, all this didn’t totally fit into the context in which Times Now was using the term. The packaged product here was news and opinions itself and the targets - viewers and social media users. Like a sales manager presenting his achievements in the monthly meeting, the Times Now anchor gave a brief break-up of the channel-generated hashtags and their respective impressions.

He concluded: “We are buzzing on Twitter” and “there is a reason why we are India’s election news headquarters.” This was not the first time that television news media held up social media reach, engagement and reactions as the gold standard for gauging effectiveness. Times Now just manages to take things to a whole different level.

The Newshour Debate is the flagship programme of Times Now. It usually starts with the build-up, which could be mistaken for a world heavyweight boxing championship and not an everyday debate. A timer on the screen, like a new age replacement for the wall clock, tells everyone exactly how many hours, minutes and seconds remain before the lord arrives and the executions begin. If one looks closely, the subliminal message built into every Times Now blue screen is the face of Goswami; every transition screen flashes a banner about the programme too. After every show, before every break, the show is mentioned. All other programmes on the channel exist only as billboards for the Arnab Hour.

Once the show starts, another counter starts running. This is the one counting the number of tweets on the hashtag being run by the channel. Though Twitter maybe in trouble in the market owing to stagnation in user growth, it remains very popular as a source and feedback mechanism for news. The Twitter hashtag starts well ahead of the show so that it gets traction and adds to the parallel drama onscreen. On an average day, the counter will show anywhere near 5000 tweets at the start of the show and ends with the counter showing just below 30,000 tweets.

This serves many purposes. One, it tells the advertisers that if they want to be seen, the numbers show that this is the show to be on. Secondly, it reinforces the view that the News Hour and Times Now are the most active and followed space. Finally, by showing the running meter and merging it into the context of the shrill discussion, the small counter provokes people to tweet and take out their anger online, something which the anchor has taken up as the single most important purpose of the show. It is here that ‘potential impressions’ become so core to the working of Times Now.

There are two possible variations of Twitter impressions: potential impression and actual impression. Potential impression is the total number of times a tweet from an account or mentioning an account could appear in users’ Twitter feeds during the report period. Potential impression measures the total number of views possible. Actual impression measures how many views a post received. The number of actual impressions a tweet receives will always be lower than the number of potential impressions possible.

Irrespective of this handicap, Twitter serves many other purposes. Twitter’s intellectual engagement is skin deep - not encouraging a nuanced discussion of anything and this sits perfectly with the Times Now debates. Sentiment Analysis shows how the Twitter world responds to a point of view. Key words picked up from the tweets aid in grouping them as positive, neutral or negative. Twitter thus shows clearly how online people view a news story, the emotions it evokes and provides not just simple feedback but also clues as to the desirable way forward.

Since the actual audience and their response can never be authentically known, in real time or otherwise, social media, mostly Twitter, has become the de-facto mechanism for engaging the targeted audience. Twitter impressions have become vital. Times Now takes its potential impressions and Twitter hashtag handles very seriously.

While it is obvious that targeting social media users is a practice, what is not so obvious is the utility of such an approach. How many people actually use Twitter in India? Does success online convert into anything substantial? Why are the social media users the only kind of people who matter for the channel? Are debates and topics decided on the basis of online feedback? If so, given that there is an editorial agenda that is guided by the emotions expressed online, how often are discussions held with the aim of generating further engagements and impressions?

Who is the target audience?

Who are the people who actually watch Times Now or for that matter other English news channel? In Times Now’s case, the targeted audience is very clearly defined. The channels’ own description about what they do provides clarity about the composition of this targeted audience, as also the reason why the channel has been successful in its targeting.

Times Now, in its own words is, “a Leading 24-hour English News channel that provides the Urbane viewers the complete picture of the news that is relevant, presented in a vivid and insightful manner, which enables them to widen their horizons & stay ahead.” Not just urban, but urbane as well.

As to who these urbane viewers are, one needn’t wonder. The channel’s YouTube outlet provides the explanation, “Today, TIMES NOW boasts of over 33 million urban and affluent Indian viewers every month and an ever-increasing following in 27 countries across 4 continents.”

33 million out of a total population of 1,210.8 million (Census 2011 figures) is a 2.72 percentage over a thirty day period. That is, every month, out of a hundred Indians three people watch Times Now. And if one is to believe their words, these are urban and affluent people with the money and the means to express themselves. It shouldn’t be surprising then that the channel uses Twitter and other social media reactions for calibrating its content. It is the tastes of this online population that Times Now tries to reflect in its content and it is their opinions that determine the agenda. Times Now shows this group the world through their lens, in the way they like seeing it, and that is why channel is immensely popular with them.

Who are these people and why are they having a disproportionate say? Before discussing the middle class bias, it’s useful at this point to make a comparison of the “impressions” made by different channels to make clear the stark divide.

The stark divide

According to the Business Standard, the Broadcast Audience Research Council (BARC) India is the only ratings body in the Rs 54,200-crore Indian TV sector after its joint venture with TAM. BARC India has more than 460 channels that have adopted its watermarking technology, accounting for over 97% of Indian TV viewership and adverting revenue.

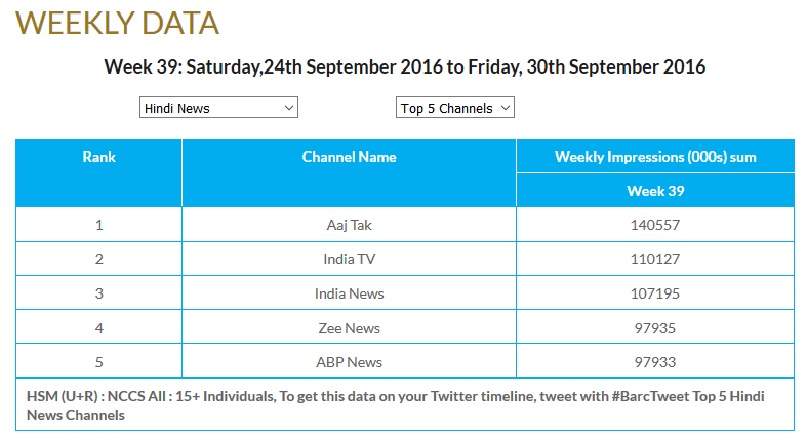

This also makes it the world’s largest television audience measurement service. BARC measures the viewership habits of India’s 153.5 million TV households: 77.5 million in urban India, and 76 million in rural India. Eight months after it launched its TV ratings service, BARC India re-named its popular viewership measurement metric Rat'000 as Impressions'000.

The reason for this, as explained by Partho Dasgupta, CEO, BARC India, was that, "We are preparing for the future. When we get into digital measurement, viewership will be measured in Impressions and in order to maintain uniformity and avoid confusion we decided to rename Ratings '000s to Impressions '000s". Impressions ‘000 represents the number of individuals in 1000s of a target audience who viewed an "event", averaged across minutes. This shift signals a uniform approach for both TV and online platforms, a philosophy which Times Now had adopted long time back because of its unique targeted audience.

The comparison makes it clear that the English news channels’ viewership is but a fraction of the overall TV news viewership. But the relative unimportance of Hindi news channels compared to English channels points to a mismatch. The first ever interview by a sitting Prime Minister of India to a private television news channel in the country was to Times Now. For the first time after his political debut in 2004, when Rahul Gandhi decided to give an interview in 2014, it was to Arnab Goswami on Frankly Speaking. It is not how many people watch something that is important but also who.

The middle class bias

There is no clear definition of the middle class in India and the use of different criteria has given rise to widely different numbers. India has 23.6 million adults who qualified as middle class in 2015 as per the findings of Credit Suisse, a global financial services firm based in Zurich, in its Global Wealth Report 2015.

A McKinsey Global Institute study in 2005 using National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) data said 50 million people were middle class. A study by the World Bank in 2005 estimated the middle class at 264 million. Television channel CNN-IBN in its middle class survey in 2007, out 20% of the population or slightly over 200 million people, as middle class. So we have anywhere between 23.6 million to 264 million strong population falling under the middle class tag.

As per the lowest estimated figures, published by the Global Wealth Report 2015by Credit Suisse, he Indian middle class has a 22.6% share ($780 billion or Rs 5,070,000 crore) of the country’s wealth, while sections above the middle class share about 64% of the wealth. Combined, they own 86.6% of the country’s wealth.

Seen in this light, the heavyweight status of English news channels becomes clearer, despite being watched by a tiny number. This also throws light on why these channels have a disproportionate significance compared to Hindi channels. The few Indians who watch an English news channel such as Times Now are the people whose opinion really matters. They have the money and the voice. It is also why their opinions are given a repeat run through a cyclical process of feedback-led content generation, for which social media acts as the perfect conduit. It is as if the rest do not exist.

In 2016, Twitter is projected to reach 23.2 million monthly active users in the region, up from 11.5 million in 2013. In 2014, India had 112 million Facebook users which by 2016 had grown to 148 million users. Compared to all this, in 2013, India had 129 million TV-owning households. According to projections in the Confederation of Indian Industry/PwC report, in 2017 this will grow to 146 million. As per the latest Census data available, 200 million Indians have no TV, phone or radio.

There remains a stark difference between TV penetration in rural and urban India: just one third of rural households own a TV set, while over 75% of urban households own one. TV penetration is highest in Delhi (88%), followed by Tamil Nadu, Punjab, Chandigarh and Puducherry. Bihar has by far the lowest TV penetration of any state at just 15%. The gap between India and Bharat is real and measurable.

TV is predominantly an urban phenomenon and its content reflects this bias one way or the other. Within this section, a gradation is applied depending on the relative importance of the audience in the greater scheme of things. For example, viewers of English news channels belong to the ‘’urbane and affluent’’ sections which Times Now refers to in its website and targets through its programmes.

The use of social media as a content-generating mechanism only adds to the already inherent bias. The policy makers, bureaucrats, judges, businessmen, and journalists who help run the country all watch the same channels and interact with the narratives put forward by them. Any point of view that appears on a national platform gains credence, even if it is a playback of something that exists only in the minds of the affluent people who inhabit these platforms.

Where does the problem lie?

The objective of journalism is to provide facts and information to citizens who can then make their own judgments. Why the reaction of people should even matter for a news channel is a question that might require redefining today’s journalism altogether. After all, news is news. It cannot be tailor-made for different requirements, like an entertainment channel. But for those such as Times Now involved in trading opinions as news, reactions - negative or positive and preferably polarising - matter.

Most other language news channels are somewhat limited in their discussions on issues of national importance as the quality of the discussion is compromised by the persons taking part. Except for the few national Hindi news channels, the rest of the Indian language news channels almost never even get national level spokespersons from the political parties to take part in their debates.

Also, most Indian experts, educated abroad, display greater ease in English, limiting analysis in other languages. Owing to this handicap, regional channels often let the narrative be determined by the ‘national’ English channels when dealing with anything outside their expertise. This is where the virus creeps in. The fact that the narrative of a channel like Times Now is a very narrow one tends to be overlooked owing to a lack of alternatives.

The job of the media in a democratic country is traditionally defined as being the link between the Government and the people. Telling the people what the Government is doing and conveying to the Government what the country wants. By limiting itself to the urbane and affluent, by focussing on the tweeple people alone, a channel such as a Times Now is not the voice for the people, but for a few people.

There is a difference and this needs to be understood. What Times Now and Arnab Goswami do is claim they speak for the nation while conveniently ignoring the voiceless majority. Even if one were to use the biggest middle class figure of 264 million, at the very least, this keeps three-fourths of the country outside the purview of the national news channel’s agenda.

India is much more than the worldview of the urban (or urbane, according to Times Now) and affluent. The real voices of India seem to be far removed from those on the TV panels. The fate of those lives which lie outside the shouting box should matter too. This is why a discussion such as this is important.

The writer is a 28-year-old former Government Servant who is now a freelance journalist.