Anatomy of a journalist's murder

Was Sandeep Kothari a journalist, a blackmailer as the police and the accused claim, or an RTI activist?

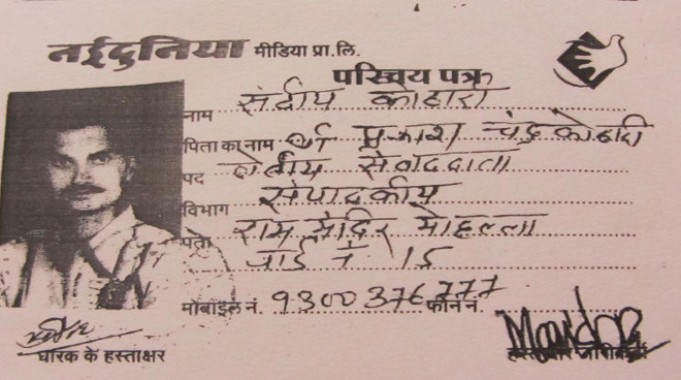

NIVEDITA KHANDEKAR investigates. Pix:Kothari~s Nai Duniya ID Card

Days after a journalist from Katangi in Madhya Pradesh was killed the question being asked is if he really was a journalist or as the police officials and accused are claiming, a blackmailer?

Katangi (Balaghat district, Madhya Pradesh): It was his death that made him famous. He was an investigative journalist and would have loved to see the kind of discussion his writings about land mafia or manganese mining mafia had generated. But alas, it was in death that he earned fame.

Sandeep Kothari, 40, was burnt to death by people who allegedly were offended by his writings as a journalist and wanted him dead. These people, along with police and administration, have termed Kothari as a black mailer, a criminal and a history-sheeter. Kothari’s family has claimed that he had repeatedly written to police about threats to his life but police did not take any action.

The incident is a perfect example of a typical politician-mafia-police nexus at a remote place throwing up reality murkier than fiction. Deep inside Madhya Pradesh, Katangi is 430 kms from state capital Bhopal and about 150-odd kms from Nagpur in neighbouring Maharashtra. A town with a population of approximately 20,000, it is known more for the areas around it, rich with forest and minerals, especially manganese.

Facts first

As has been widely reported, Kothari was returning to Katangi from Balaghat, 55 kms away, after 9 pm on June 19 along with his friend Lalit Kumar Rahangdale, who was driving the two-wheeler. About 12 km short of Katangi, a white car hit their vehicle and both of them fell off. “Sandeep bhaiyya’s leg was injured but he started running away and also asked me to run. Driver of the vehicle threatened me to run in opposite direction else I will be killed,” Rahangdale told this correspondent.

While Kothari was nabbed and dragged away in the car, Rahangdale managed to reach a common friend in a nearby village, who informed the police and the family. Next day, Kothari’s body was found in burnt condition in a forest near a railway line in Wardha district of Maharashtra.

. .jpg)

.jpg)

Gaurav Tiwari, SP Balaghat

Brijendra Geharwar, Vishal Tandi, both from Katangi, and Pappu alias Shahid Khan have been arrested and another suspect Rakesh Naraswani is still absconding, police said.

Right from day one, when the local journalist fraternity started demonstrating against the administration and the police and also demanding safety of journalists in wake of the attack on fellow journalist, the powers that be have mantained that Kothari may have been a journalist formerly but is now a criminal, a history sheeter and a black mailer. When a group of Balaghat journalists wanted to meet the Balaghat collector, he called Kothari a criminal too.

Starting 2008, there were several cases – molestation, rape, blackmail etc. – against Kothari. While police and the accused claim they are based on facts, Kothari’s family and fellow journalists from the area claim these are false and fabricated.

Sitting in their modest ground-plus-one house in a typical middle class locality near Cinema Chowk in Katangi, surrounded by documents, photocopies of police/judicial papers, Kothari’s younger brother Navin and mother Kanchan narrated the chain of events. Kothari was unmarried.

Navin said the three rape cases that were a result of complaints by women from SC or ST community, have fallen flat. “In one of the rape cases, the magistrate at Balaghat discharged him and in fact pointed out how he was falsely implicated. The two other cases, outside Madhya Pradesh, in neighbouring Maharashtra – Goberwahi in Bhandara district and Bela in Nagpur district – too could not be pursued as the women later came out in the open to tell the truth that they were forced to lodge a complaint against my brother,” Navin told The Hoot.

Only three old cases were genuine, he said. For instance, one of theft because labourers had committed the crime using a truck that was in Kothari’s name or another of some local enemity with neighbours. The others were fabricated.

Fabricated cases meant Kothari faced the implications. He was externed from the district (zila badar) twice, slapped with over a dozen allegedly false cases, including rape and molestation and, in 2012, sent to jail on charges of rape. “It was only in January 2015 that bhaiyya was acquitted. After a few months, he filed an RTI with police demanding to know the total number of cases against him and the status but received no reply,” Navin said.

Navin and another brother Rahul run the automobile spare parts shop business and financially supported Kothari all through. He had only studied upto class 12.

Kanchan, their mother, said, “I had repeatedly asked him to stop patrakaarita and work with his brothers. He did not earn anything, instead we gave him money for all his work. He would never listen to me and say, I am not here to earn, I want to stop this revenue loss to the government.”

Unequivocally, Navin, Rahul and their mother Kanchan blamed six people for Kothari’s death: Brijendra Geharwar and Vishal Tandi, already arrested; Rakesh Naraswani, named by police as suspect but still absconding; Mukesh Thakur, nephew of a state minister, and two others (names withheld as this correspondent did not talk to them).

Navin claimed that Kothari was tipped off by someone on June 19 morning that either he (Kothari) or Navin would be attacked, doused with petrol and burnt to death.

Journalist or blackmailer?

Kothari and his two brothers had their own business. He was a forest contractor, the family had a number of JCB machines (which scoop earth), and trucks. Subsequently all the trucks were sold and Kothari’s two brothers Navin and Rahul started an automobile shop. Long before that the family had a kirana shop, run by Kothari’s father.

Indrajit Bhoj, who is the bureau chief at Deshbandhu newspaper at Balaghat, was the one who inspired Kothari to become a journalist in 2005-06. “He was angry with the system that had caused such losses [to the family business]. He started with really good news reports when he wrote for Deshbandhu and Haribhoomi. He later went on to write for Nai Duniya in 2007,” recalled Bhoj.

As a Nai Duniya representative, Kothari was supposed to do three things. He was to report, bring in advertisements and manage circulation. (A practice common among small town Hindi newspapers).

Fellow journalist Sudhir Sharma vouched for his integrity and said, “I know for sure, he was not a blackmailer.” Manish Chowkse, outgoing president of the Katangi unit of Madhya Pradesh Shramajivi Patrakar Sangh, claimed Kothari worked so hard that he had increased the circulation of Nai Dunia due to his fantastic reporting from 250 to 1000 in a few months here in Katangi. “Moreover, he was the only journalist who did nothing else. Most of us others have some or the other side business to support ourselves.”

Navin showed documents about how their brother used RTI effectively to dig out wrong-doings of the land mafia, mining mafia and even the illegal colonizers. Three prominent cases were: A) A huge residential complex being built brazenly in violation of all town and planning laws. B) More than 100 acres of agriculture land was being illegally colonized by unlicensed colonizer. This led to huge revenue losses for the government. C) Almost 250 tonnes of illegal mining of manganese was going on from the area around Tirodi in the neighbourhood.

Tarang Agrawal, a social worker from the area, said, “Kothari was not just another journalist. He effectively used RTI to dig out information about all such wrong doings. When he filed RTIs, officials of the respective department were tipped off and (to avoid reports against them) implicated him false cases.”

Agrawal further said that at times Kothari went beyond his journalistic duties and lodged formal complaints either himself or on behalf of others with the higher ups against the local corrupt officials. This rubbed the officials and the mafia the wrong way and they did indeed threaten him.

Earlier too Kothari had received death threats. He had lodged a number complaints at the Katangi police station. But except for receiving it, the police did nothing,” Navin said, adding, “Had the police taken any action, my brother would have been alive.”

Gaurav Tiwari, Superintendent of Police (SP) Balaghat, visited Katangi on June 24. He interrogated the two already arrested, met with local journalists and also with Kothari’s family and his lawyer.

Refusing to call him or treat him as a working journalist, Tiwari claimed that police record showed him as a culprit who has been convicted in four cases, as a blackmailer and someone who had several cases still under trial against him. “The accused arrested told us during interrogation that Kothari used to dig information using RTI and then harass officials. He was a blackmailer,” Tiwari said, but said it was an unverified claim.

To a pointed question as to why did the police never act on the number of applications that Kothari had filed about threats to his life, the SP called him a “criminal” and said, the police can’t act on the application of each and every criminal. He also pointed out that three of the accused and Kothari were known to each other for quite long, they had been business partners and because each knew the others’ trade secrets, they were blackmailing each other.

Refuting the claim that Kothari was a black mailer, Atul Kumar Jain, Kothari’s lawyer, said the journalist’s office room – which is under lock as the key was found on Kothari’s body and is still with the police – is full of neatly arranged subject wise files. He dug out dirt using RTI and then with full preparation, wrote his report.

The latest provocation, which possibly led to Kothari’s murder, Jain speculates, is that Kothari had sent legal notices to 28 persons. About 40-odd people had signed a complaint to the police alleging that Kothari was blackmailing them. Police had not registered a case but when Kothari came to know about the complaint, he obtained a copy of it and then sent legal notices to the six main people, including the three accused, and other signatories.

“The other people, who were kept in dark when they signed the paper, were rattled and started pestering these six main people as they didn’t want any court notice or a case. Perhaps, this bugged them and prompted them to take this extreme step,” Jain said, adding, “Kothari is not a blackmailer as they claimed. Instead, he was being framed in yet another false case.”

Political Pressure?

Kothari’s family and a number of journalists alleged that the police have not been investigating the case and avoiding arresting Naraswani owing to the alleged involvement of Mukesh Thakur, nephew of Gourishankar Chaturbhuj Bisen, Madhya Pradesh’s Minister for Farmers’ Welfare and Agriculture Development.

The politician-mafia-police nexus was discussed time and again by all journalists even as Navin repeatedly said police are in connivance with the mafia as several political interests are served.

Kishore Samrit, BSP leader and a former MLA from the area, too supported the politician-mafia nexus vis-à-vis the involvement of Bisen. Samrit, who said he knew of Kothari since 2007-08 and had met him first in 2013, alleged that “Mukesh Thakur is involved in the fake currency note racket along with Naraswani. Police calling Kothari a blackmailer is no surprise. Police officials are susceptible to political pressure simply because they are afraid of transfers.”

Ashish Verma, a journalist who runs ‘Jag Prerna’ newspaper from Balaghat and Gondia, pointed fingers at police connivance with the mafia. “The mafia and even the police is making it out as a matter related to land deals. (Minister) Bisen’s role is suspicious in the whole matter,” Verma claimed.

On phone from Balaghat, Bisen denied putting any pressure on the police. “They are doing their job impartially. Otherwise, why would they have arrested three accused? Narswani too would be arrested. I am here as a responsible representative of the Government of Madhya Pradesh and I will ensure that Kothari’s family gets justice.”

Expectedly Tiwari, the SP, too denied any such political pressure. “We have been able to re-create the whole crime scene and we now know there are seven people involved in the murder. There is no political pressure whatsoever, we are sure we will arrest all others soon,” he said.

End word:

With a pittance for salary, most stringers or similarly placed journalists at small towns earn much less than they need to run the basics of a family. As pointed out by few of the journalists in Katangi, many of them have some side business to run and do not depend on journalism to run their kitchens.

If not in that scale, but as in Delhi or any other state capital, rich people (read, businessman, mafia, politician and corrupt officials) in small towns too do not wish to be rubbed the wrong way. For people like Kothari, capitalist forces trying to subvert the system as well as vested interests prove to be a hurdle vis-à-vis negative news coverage. Some remain clean, some fall prey. In the past, there have been cases – especially involving journalists from smaller brands of newspapers, who have resorted to unscrupulous means giving a chance to administration and police for name-calling journalists.

However, in this case, even when police and administrative officials termed Kothari as a blackmailer, only one journalist from Balaghat – that too off the record – claimed Kothari was indeed a blackmailer. “From smaller newspapers (Hari Bhoomi) to relatively a bigger brand (Nai Duniya), his journey was fast and the transformation faster. Bade brand mein jaate hee uske par nikal aaye. (He changed for worst after joining a bigger brand). Greed can change anyone. He did resort to black mailing. I tried to stop him but to no avail. Usape junoon sawar tha (He was adamant),” this journalist, who runs his own paper said.

But no other journalist, neither from Katangi nor Balaghat, said any adverse thing about Kothari.

Seeking to water down police’s contention that Kothari was not a journalist now and he was not covering anything controversial now, Bhoj, who was also part of the delegation that submitted a memorandum to the Balaghat Collector about the safety of journalists earlier this week, said, “Once a journalist, always a journalist. So what if he was not covering anything now, but he had been an active journalist. We want justice, the culprits should be punished.”

Perhaps the debate can go on continuously. But Pramod Trivedi of from Nai Duniya’s Indore headquarter, who was in Balaghat to keep track of the case, offers a clue.

“My impression is he did not work for money. The very fact that our advertisements had gone up when he was handling the agency shows that he did not earn for himself but for the paper. He was not into blackmailing anyone.”

Nivedita Khandekar is a Delhi-based independent journalist. She focusses on environmental, developmental issues apart from media matters. She can be reached at nivedita_him@rediffmail.com or you can follow her on Twitter at @nivedita_Him

Such articles are only possible because of your support. Help the Hoot. The Hoot is an independent initiative of the Media Foundation and requires funds for independent media monitoring. Please support us. Every rupee helps.

Subscribe To The Newsletter