Assam’s NRC: doing justice to its complexities

Rarely has there been as complex an issue to report on as the National Register of Citizens (NRC) currently being compiled in Assam. What adds to the complexity is the fact that the North East has always been an under-reported region in the English press.

The NRC has aroused strong feelings both in and outside Assam, perhaps more outside the state than in it. Provocative rhetoric by political parties has found both echoes and opposition on social media, as well as in the foreign media. But, is it really what it’s made out to be: an attempt at ethnic cleansing?

A study of five national English newspapers revealed that the issue is far more layered than is made out to be. Those reducing it to a religious/linguistic issue are doing injustice to the hopes as well as fears tied to it. These hopes and fears, indeed, the issue’s many complexities, have been brought out by the English press. But it appears that the political rhetoric of the ruling party which is using the NRC for its communal agenda, has drowned every other aspect of it.

Most politically aware people know of the long-standing ``infiltrators’’ issue in Assam which led to the horrific Nellie massacre of Muslims in 1983, and the rise of the All Assam Students’ Union and the Asom Gana Parishad, as well as later, of the All India United Democratic Forum.

More recently, Narendra Modi’s divisive promise made during his prime ministerial election campaign, of throwing out those who came to Assam to ``steal jobs’’ (Bangladeshi Muslims), but providing shelter to those driven out because of their religion (Bangladeshi Hindus), is still fresh in our minds.

Add to that headlines quoting West Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee’s warnings about the NRC leading to ``civil war’’ and a ``bloodbath’’.

Taken together, the impression created was that the NRC was an exercise calculated to make non-citizens out of large masses of people, mostly Muslim, resulting in disenfranchisement of non-BJP voters.

This impression was strengthened by online petitions such as the one started by the NGO Avaaz, provocatively titled: ``India: stop deleting Muslims!’’, which was widely forwarded.

How did the English mainstream press deal with this complex issue? A survey of five English newspapers: The Indian Express, The Times of India, Hindustan Times, The Hindu and The Telegraph, was an education for this reporter.

The role of the Supreme Court

The first thing that emerged was that every aspect of the NRC was being directed by the Supreme Court, to the extent that the two-judge bench recently threatened the two men entrusted with conducting the exercise with jail for speaking to the media, pointing out that the Court was the sole authority to issue directives on the NRC.

All that these men had done was reassure the 40 lakh left out of the NRC’s final draft published on July 30, that they had enough avenues still left to stake their claim to citizenship. With their mouths sealed, now there remains no one to answer the doubts being raised by those left out, as this report shows.

Surprisingly, while there have been a number of opinion pieces in these papers against the NRC, only one, by academician Alok Prasanna Kumar in The Hindu, criticized the role of the Supreme Court.

Sanjib Baruah in this piecein the Indian Express also wondered at the silence of the court on what will be the eventual fate of those left out. In one of its edits, The Hindu referred to ``an unrelenting Supreme Court’’.

Interestingly, the two-judge bench hearing the NRC petition is headed by Justice Ranjan Gogoi, one of the four judges who held a press conference in January drawing attention to the troubling situation in the Supreme Court. He is slated to be the next CJI.

The current NRC came about due to a PIL filed in the Supreme Court in 2009 by an Assam NGO, Assam Public Works (APW). The idea of the petition came from a Guwahati couple: Pradip Kumar Bhuyan and his wife Banti. Strangely, none of these papers could explain what exactly prompted this elderly couple to approach the court. Their main concern was the presence of ``illegal citizens’’ on Assam’s electoral rolls. They also wanted regularization of all those who had migrated from East Pakistan and were accepted as Indians under the Assam Accord.

But what was the immediate provocation for their PIL? All reports said the couple preferred to remain in the background, but surely this information could have been gleaned from APW? Only one report spoke about an incident of violence that provoked them into action, without explaining that incident for the benefit of those living outside Assam.

Similarly, there were many profiles of Prateek Hajela, the face of the NRC, but none of them brought out the man’s personality.

However, what emerged clearly from every paper was that the NRC cannot be viewed through a religious lens.Consider this comment from a BJP MLA, Rama Kanta Deuri, whose name, and those of his family, did not feature in the final draft. “My name does not figure because I did not apply. As a tribal (Tiwa) and an original inhabitant, I will not apply under any circumstances,” the Morigaon MLA said. All the reports showed that a diverse range of people, both in terms of religion and class, were affected by the NRC. It was opposed and supported by both Hindus and Muslims; families of both had been divided by it, with some family members excluded and others included; and the poor of both communities had been forced to sell off their means of livelihood, be it cows or boats, to pay the expenses involved in proving themselves to be citizens.

Out of NRC, but clearing cobwebs of ancestry in Kolkata’s archives

NRC a death warrant for Assamese people, says ASM

A two-part report in The Hindu brought out how the NRC had succeeded in vindicating the bitter struggles of groups opposed to each other ideologically. Family members of those who had died for opposite versions of the ``cause’’ – Muslims who agitated against an earlier attempt at an NRC, and Hindus who agitated against ``illegal immigrants’’, felt that the NRC’s final draft showed that the sacrifice had not been in vain.

This Express report from Nellie, the site where 1800 Muslims were massacred on suspicion of being ``infiltrators’’ in 1983, quoted its residents as hoping that after the NRC, their surnames wouldn’t mark them out. “Of course, we want the NRC,” says Abdul Karim, a resident of Borbori, among the 14 villages hit by the 1983 massacre. “Even we are against ‘foreigners’ who came after 1971 (the Bangladesh War). Maybe with the NRC, the ‘Miya Khedao Andolan’ will finally be over.” Karim and his immediate family have made it to the NRC.

When the final draft of the NRC came out on July 30, it broke another myth, one spread by the Avaaz petition: that only Muslims were likely to be excluded from it. Of the 40 lakh who’ve been left out, the Namashudras, a Hindu Scheduled Caste community that has been crossing over to Assam since the 50s because of religious persecution, number six lakh, if one were to believe the claim of their spokesmen. It was the Namashudras of West Bengal who blocked trains in protest after the final draft was published.

Another one lakh of those left out are Gorkhas.

Another surprise emerging from the final draft of the NRC was the small number of exclusions from the Barak Valley. For those who know little about Assam, this name means little. Unfortunately, there was just one report which explained why these figures were such a surprise – the Valley is seen by Assamese as the stronghold of Bengali migrants, and hence, it was expected that a large number of those excluded from the NRC would be from here.

While the number of exclusions from the Barak Valley may be small, it’s important to know the religion-wise break-up of those excluded. That may prove or disprove the impression in some sections in Assam, and among liberals outside Assam, about the entire exercise being religiously motivated.

What all of this showed was that the BJP’s black and white Hindu-Muslim pitch did not reflect the ground reality in Assam. Already, the AGP has threatened to withdraw from its ruling alliance with the BJP if the latter enacts its Citizenship Bill, aimed at giving citizenship to Hindu migrants alone. Assam is divided over this Bill, with the CM himself facing protests over it.

Sarbananda Sonowal faces people's anger at Charaideo

Sarbananda Sonowal becomes target of anti-foreigner stir he once led

Ironically, the liberal, secular social media space also took the BJP-projected religious divide as a given. The Avaaz petition ``India: Stop Deleting Muslims!’’, got such an immediate and massive response that the NRC head started a counter petition, which could get only a fraction of the signatures Avaaz got, reported The Telegraph.

Incidentally, Avaaz and those who signed its petition might be surprised to know that among those opposing its petition were Assamese Muslims.

As the reports showed, the primary divide in Assam remains that between original inhabitant and ``outsider’’, Assamese and Bengali, and that cuts across religious lines. So, Mamata Banerjee’s fiery statements against the NRC in Bengal led to her embarrassed and furious party men resigning in Assam. Assam Congressmen too, forced the party to rethink its initial opposition to the NRC, to the extent that the Congress started claiming ownership of it.

Interestingly, Mamata Banerjee’s concern about those left out of the NRC however, may be just political opportunism. Her own administration had contributed to the large number of people left out, by its delayed response to verification requests from the NRC, which are essential to establish citizenship. A PTI report in the Times of India labelled her government as the biggest defaulter in this regard, an allegation made by the Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India, Sailesh.

But a report by Prabin Kalita in the same paper on the same day (probably another edition), showed that other states had been even more negligent in responding. Kalita had culled this information from the NRC’s state coordinator’s affidavit in the Supreme Court.

Why then did Sailesh single out Mamata Banerjee’s government as the biggest defaulter to the PTI? Was this accusation politically motivated?

Given the BJP’s continuing divisive religious propaganda on this issue, as well as the heightened communal temperature in the country, newspapers had to be specially cautious while reporting on it. Ironically, reports showed that Assam remained peaceful both when the first draft was published in December and when the final draft came out last month, though as only The Telegraph reported, attempts were made to create trouble through fake whatsapp videos. The police had to step in to advise people not to believe these videos.

Significantly, the Assam government sent for additional forces and expectedly, positioned themin Muslim areas. While most reportage avoided any communal slant, in a few instances, such as the one below, pictures accompanying certain reports lent credence to popular communal stereotypes. 200 'wrong' inclusions in Morigaon.

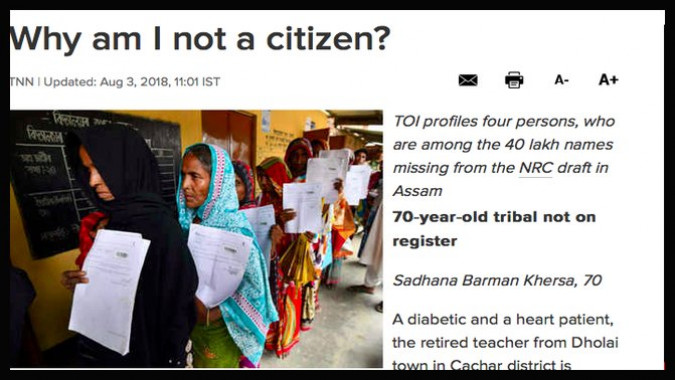

The report was about people declared to be ``foreigners’’ by the state’s Foreigners’ Tribunals, or those whose cases were pending before these Tribunals, having been included in the final draft of the NRC. The picture showed a line of obviously poor Muslim men holding documents, waiting in front of some office. Nothing in the text, however, indicated that these ``foreigners’’ who had been included were Muslims.

In two other cases, only one community was quoted, as in this report from Pune where only Assamese Hindus were quoted as welcoming the exercise.

Maybe it was difficult for the reporter to trace out Assamese Muslims in Pune?

Similarly, this report on women who have been excluded (and a new rule introduced in May makes married women particularly vulnerable to exclusion) interviewed only Muslims.

Notwithstanding the coverage by these papers of every aspect of what the NRC meant to the residents of Assam, one failed to get the effect of this vital exercise on the daily lives of the residents. Only The Telegraphhad two interesting reports showing decreased attendance at hospitals that were normally crowded. As the director of the leading cancer institute in the region said, "Getting enlisted in the updated NRC is like a life and death situation for some patients... It seems they prefer missing their check-up dates to missing NRC-related work."

Finally, the most important issue remained unaddressed: how seriously has migration from Bangladesh impacted the state?Has the fact of ``illegal immigrants’’ voting adversely impacted State policies? How real is the threat to indigenous Assamese culture? Had the ``infiltrators’’ indeed taken away jobs and land from the Assamese? How deep is the Assamese-Bengali divide in everyday terms?

In these national newspapers, no such analysis was forthcoming – not in the last two months preceding the publication of the final draft at least. Considering that the NRC has been a life-changing exercise for every resident of Assam, with a few of those excluded from it committing suicide (these include both Hindus and Muslims), one would have expected such an analysis.

Chanakya’s otherwise excellent analysis of the ramifications of the NRC asked whether the fears of the Assamese were ``exaggerated’’ without answering the question.

Also surprising was the omission of any Assamese viewpoint on the opinion pages of these newspapers.

Where the reports excelled however, was in bringing out the hard, impersonal and indeed callous nature of the NRC. A number of reports, written with deep compassion, left one in despair at the heartlessness of it all. How can one expect a largely illiterate population to keep track of old documents, when even educated citizens may not have all the documents they need? How cruel is it to make people bring their old parents from distant villages to verify their relationship, and then reject their claim because the parent makes a mistake about his child’s age? These reports were specially heartbreaking.

Left out of NRC in Assam, two former IAF men fight nationality battle

Indigenous Assamese Muslim woman struggles to free herself from 'foreigner' tag

NRC: Assam farmer who committed suicide was afraid his family would be divided

Those finally excluded by the final draft of the NRC will first have to approach the Foreigners’ Tribunals. Along reportin the Expressshowed how flawed they are.

This report brought to light alarming new developments. While earlier, judges were supposed to head these tribunals, now, lawyers can do so too. Now, there is pressure to dispose off cases within 60 days. But that’s barely enough for those ``accused’’ of being foreigners - and the burden of proof is on the ``accused’. Just getting copies of electoral rolls, essential to prove their case, can take a long time.

The report quoted lawyers describing how nervous and largely illiterate villagers are asked ``mathematically puzzling questions’’ in the Tribunals.In one case, a brother could not correctly say which year his sister was married. So she was declared a foreigner.

The report ended with a quote from a lawyer who has handled many cases, including his own, before these tribunals: “Tokhon justice chilo, ekhon bhoy laage (Then, there was justice, now there is fear)” he said, referring to the functioning of the Tribunals before the BJP government took over and started pressurising them to show results.

Only the Supreme Court knows what is to happen to those finally excluded, once all appeals have been exhausted. A TOI report said a new detention centre is being built for them, but no reaction was sought from political parties and human rights activists to this frightening news. Indeed, human rights activists were largely ignored in the vast coverage, which had only community leaders and politicians’ quotes. Given that this was an issue on which the UN chose to warn the Indian government, shouldn’t Assam’s human rights defenders have been quoted?

However, the press said what human rights defenders would have. These edits in The Hindu,

On the dangerous rhetoric post release of Assam's draft NRC

this interview in the TOI,

If only Hindus are natural citizens, it is a blow to India’s idea of citizenship…

and this analysis--

The NRC exercise will lead to an upsurge in identity politics in the Northeast

brought out what the BJP seems to have forgotten: we have always been a land that welcomed ``outsiders’’, never mind their religion.

The latest news from the Supreme Court however, is encouraging. The Court has asked various organisations to submit their views on ways to review the final draft of the NRC.

In the opinion of this writer, the original sin that led to this problem must lie on Partition and its unnatural drawing of boundaries. Those crossing over into what was once part of the same country are paying the price of an unforgivable decision taken by our pre-Independence leaders.

Jyoti Punwani is an independent journalist based in Mumbai.