Dimapur lynching: a travesty of reporting

The way Nagaland's English newspapers covered the events leading up to, and including, the lynching of an 'illegal Bangladeshi immigrant' suggests that they were complicit in the hatred mongering.

Facts gave way to propaganda, says VIKAS KUMAR.

On the night of 3 March 2015, the people of Nagaland learnt that a Naga college student was allegedly raped by an “illegal Bangladeshi immigrant” on 23 February 2015.

Social media urged the Nagas to “wake up from slumber before they chase us out from our own homes.” A massive protest was held in Dimapur on March 4, followed by another protest on March 5 that culminated in the lynching of the accused.

The state government lost no time in suspending senior district officials. But the state Home Minister could not find time to visit Dimapur before March 9 and even four days after the incident he was clueless about the basic facts of the case. When the Nagaland Assembly session began on March 17, none of the legislators raised any questions regarding the incident. Naga News, the daily internet news update published by the government, also ignored it.

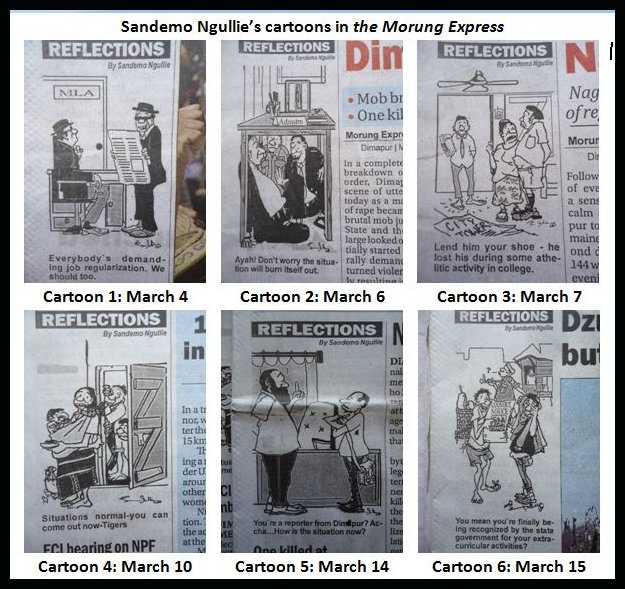

This article examines the coverage of the lynching and related developments between March 4 and March 15 in Nagaland’s English language newspapers Eastern Mirror, the Morung Express, Nagaland Page, and Nagaland Post. It does not examine Naga language newspapers and national English language newspapers - the former because of the language barrier and the latter because of the thin coverage (see Cartoon 5) and their limited circulation within Nagaland.

Nor does it look at social media because key online communities were banned after the lynching and their pages are no longer available on the internet. Others that were not banned seem to have cleaned up their pages. For instance, a day after the lynching, one of the Facebook communities posted a short article that was titled The Invisible Hand that Killed the Rapist.

The post, which was later deleted from the timeline along with at least three other posts, began with the following sentence: “I'm not at all ashamed of being a Naga for what has happened in Dimapur.” While most online communities were part of the problem, the Muslim Council Dimapur’s Facebook page provided reliable information and appealed to people in Nagaland and Assam to observe restraint.

The pre-lynching mistakes and hatred-mongering

The pre-lynching coverage – March 4 and 5 – in these four newspapers shares a number of common features. On March 4, all of them carried news items about the alleged rape on their front pages and three of them also published the accused’s photograph. Photographs published in three different dailies seem to have come from the same source.

The newspaper that did not publish the accused’s photograph used a headline that identified the community to which he purportedly belonged. All four reported that he was an illegal Bangladeshi immigrant. So, there was no room for questioning the police for prematurely branding him as a Bangladeshi. The identity of the Naga accomplice, who brought the accused and the victim together, was suppressed. Exceptions include a Naga organization’s short press release published on the fourth page of a newspaper on March 5 which mentioned the accomplice’s name and village.

All four newspapers published statements issued by civil society and student organizations that stressed the survival threat posed by the Bangladeshis who ‘steal’ land, daughters, and business opportunities. But none of the newspapers carried any investigative report that went beyond the statements of these organizations and the incomplete details shared by the police.

They did not even try to verify the essential biographical facts. In fact, many news items, at times even editorials, misspelled his name. It was as if it did not matter who the accused was as long as he belonged to a particular community. While it is understandable that these newspapers may not have the resources to support investigative journalism, they could have used the editorial space to urge restraint. But they did not publish any editorial on the issue, either on March 4 or 5.

One of these newspapers published three opinion pieces, including a two-part opinion piece, in those two days that focused on the threat posed by immigrants. One of these pieces was provocative. On March 5, the mob violence of the previous day received uncritical and, in some cases, even adulatory coverage. For instance, the main news item on the first page of a newspaper christened the March 4 protests “the Arab Spring of Nagaland.” Three newspapers also carried separate items on their first pages announcing the March 5 rally.

Post-lynching reports fail to ask basic questions

The post-lynching coverage (March 6-15) was likewise deficient in a number of respects. Once again there were no investigative reports. A number of questions remained unaddressed:

1. Who leaked the news more than a week after the crime?

2. Why did the forensic investigation start more than a week after the alleged rape?

3. Who forced the administration to allow the March 5 rally that led to the lynching?

4. Who persuaded the college principals to allow students to participate in the rally and eventually serve as human shields (see Cartoons 3 and 6)?

5. Who were the leaders of the mob that stormed the jail?

6. Why did the administration not exploit Dimapur’s notorious choke points – the places notorious for traffic jams where the police could have blocked the march?

7. Was the March 5 protest a cover for the escape of insurgents?

8. Who fired the bullet that killed one of the protestors?

9. Why were those who played an important role in mobilizing protestors not arrested or released on bail in the event that they had been arrested?

More importantly, the inconsistencies in the initial propaganda of civil society organizations were quietly mentioned, if at all, without any scrutiny. None of them highlighted the fact that the lynched man, Sarifuddin Khan, was not a Bangladeshi, let alone apologize for their complicity in the pre-lynching propaganda.

A few belated news items mentioned the correct nationality of Sarifuddin Khan, who belonged to Assam’s Karimganj district. Only one newspaper published detailed information about Khan’s identity on its first page (March 8). The media’s silence about the identity of the deceased was complemented by the insistence of a few civil society leaders that Khan was “an illegal migrant, even if he has (documentary) proof [of Indian citizenship].”

Furthermore, the newspapers did not analyze the contribution of the intra-Naga power struggle and the formation of newer anti-Bangladeshi immigrant organizations in the past year to the escalating campaign against illegal/undocumented immigrants. The outfits that were outcompeting each other in the run-up to the lynching later flatly denied their involvement without being confronted except by the writer of a letter to the editor (March 7) and a cartoonist (see Cartoon 4).

Three additional similarities in the coverage need to be noted. First, other rape cases reported around this period in which both parties belonged to the same community were given much less coverage.

Second, the newspapers did not interview the victim or the family of the accused. Nothing was reported about the accused’s Naga wife who belongs to the same village as the victim and might be her cousin.

Third, only one newspaper referred to an earlier instance of lynching in Nagaland. But even that newspaper did not note that only non-Naga rapists were lynched.

On the edit pages too, complicity

We can now turn to post-lynching editorials. Overall 37 editorials, including one From the editor’s desk and a quote published in lieu of an editorial (Ken Kesey’s The truth doesn't have to do with cruelty, the truth has to do with mercy), were published over the ten day period following the lynching.

Of these, 14 directly addressed the issue. One of the newspapers published its first and only editorial on this issue a week later on March 12. The other three newspapers published four or five editorials starting on March 6. Four of these 14 editorials advised outsiders about how not to cover such incidents and rightly argued that all Nagas should not be equated with the barbarism of a few thousand.

Four editorials gave advice to administrators and legislators. One of these four editorials that was published on March 12 drew the attention of administrators and legislators to Samuel Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations and Who Are We. Five editorials were introspective but even these did not go beyond general reflections on the burgeoning void within Christian Naga society.

It should be noted that one editorial failed to condemn the violence (March 6), describing it as “the required message loud and clear to the administration.” An opinion piece published in the same newspaper on that day also dwelt entirely on the existential threat posed by illegal immigrants.

Analysis of opinion pieces reveals a similar unwillingness to probe deeper into the problem, even though most of them criticized Naga society for what happened and how it sullied the image of Christian Nagas. At least two opinion pieces published during this period contained provocative content.

One is not arguing that newspapers should have overlooked the serious implications of undocumented immigration for small tribal communities. However, they should also have alerted readers to the growing population, irregular rains, shortening jhum cycles, deforestation of hills, soil erosion, growing literacy, and stagnant economy that are pushing Nagas towards urban Dimapur and the fertile, sparsely populated plains in its vicinity. Similar factors explain the influx of Bengali-speaking Muslims, whether of Indian or Bangladeshi origin, into Dimapur district.

In addition, irregular rains, shifting cultivation cycles, deforestation of hills, soil erosion, and growing literacy are also pushing Nagas toward these plains where they have to compete with immigrants.

In Dimapur everyone needs the immigrants. Businesses need cheap immigrant labour, politicians need vote banks, and insurgents need foot-soldiers to carry out criminal activities including extortion (especially when not many Nagas seem to be joining them).

Even civil society needs immigrants to explain the incidence of crime and the unusual fluctuations in population figures that are largely driven by statistical competition between tribes.

But the unemployed Naga youth (see Cartoon 1), who disdain the menial jobs done by immigrants, cannot be expected to show restraint. They are goaded to reclaim jobs and business opportunities ‘stolen’ by immigrants and redeem the self-respect of the Naga male rendered impotent by the "rapist jihadi" Muslim who is harassing Christians across the world.

On the internet, local grievances and global outrage roll into one with one news item or social media post mentioning how (Muslim) immigrants are encroaching upon tribal (Christian) territory and the other drawing attention to Islamist terrorist attacks on Christians in West Asia, Northern Africa, and Nigeria. In short, a local territorial conflict with roots in a burgeoning ecological crisis is transformed into what I call a local ‘instantiation’ of a presumed global war of religions, ie an abstract idea (the clash of religions) is converted into a concrete local example.

The situation is made worse by the cynical calculus of politicians who think that they can divert attention away from the real problems by allowing a little bit of lawlessness, and by the bureaucracy which does not want to take tough decisions (see Cartoon 2).

They do not understand that the unemployed, literate, and socially networked youth is an unpredictable creature whose Facebook posts target illegal immigrants in the morning, extortionist insurgents in the afternoon, and corrupt politicians in the evening.

I will end with a long quote from Charles Mhonthung Ezung’s article Insanity and Barbarism in the Land of Christ (Nagaland Post, March 9; the Morung Express, March 10):

I did not teach my students to take the law in their own hands but I hang my head in shame and disgust at this gross inhuman act. On the evening of 5th March I was aghast at the sight of parents driving to the City Tower with their children to witness the lynching of the alleged rapist.

What kind of human beings are we, parents trying to bring up children by letting our children watch such barbaric act which the entire civilized world has condemned. We were condemning the ISIS for summarily executing Christians for no fault of theirs, but today we are no better than the ISIS. . .

Enough of the oft repeated rhetoric that we Nagas are "head hunters" and ‘fierce warriors” and do not brook crimes against our people. However, this act of lynching an unarmed man by a thousand strong mob is no act of bravery. Our forefathers fought enemies of equal strength.’

(Vikas Kumar teaches economics at Azim Premji University, Bangalore. His interests include the economics of religion, the political economy of conflicts and statistics, and Indian history. He is presently studying the relationship between development policies, ethnic politics, and government statistics).

Such articles are only possible because of your support. Help the Hoot. The Hoot is an independent initiative of the Media Foundation and requires funds for independent media monitoring. Please support us. Every rupee helps.

Subscribe To The Newsletter