Getting into a twist over noodles

HERE’S LOOKING AT US

Jyoti Punwani

The media coverage of l’affaire Maggi has thrown up a few questions. What should be the media’s attitude when a multinational giant such as Nestle is prima facie indicted for not following quality standards?

The obvious answer is that the media must report the findings against the corporation’s products and also its defence. Mostly, the press did that.

However, there were two angles taken by the press which went beyond this focus. One was the damage done to the brand both in reputation and business. Nothing wrong in reporting that. However, when talking of the company’s reputation, should not its entire background be taken into account, or should its reputation in India alone be considered?

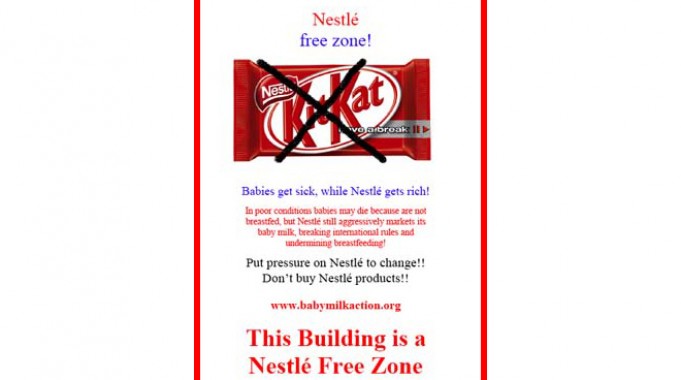

Just one piece in the Indian Express informed readers about Nestle’s controversial record worldwide. If there’s a `Boycott Coca-Cola’ movement across the world, there is also a `Nestle-free zone’ movement in the West. This is the company whose chairman said two years ago that the belief that every human being had a fundamental right to water was `extreme’; water to him was a product and like any product had a market value.

Corporate Watch, a UK-based research group, lists a number of well-documented charges against Nestle. So does Greenpeace. The following instances are taken from their websites, and have been cross-checked with reports from other websites and newspapers.

Nestle’s dubious track record

Its aggressive and allegedly misleading advertisements for baby food, flouting WHO norms, led to a Nestle boycott campaign which started in the US in 1977 and later spread to Europe. In 1984, Nestle agreed to conform to WHO standards, so the boycott was withdrawn, but in 1988, finding that it had not kept its promise, it was revived.

Agencies such as the International Baby Food Action Network have pressurized Nestle through this campaign to modify its advertising of baby food but their limited success has meant the boycott of all Nestle products continues.

On occasion, the giant has had to bow down before public opposition or the courts. For instance, in 2010, a Greenpeace campaign against Kit Kat resulted in Nestle committing itself to stop using palm oil sourced from companies engaged in activities that were leading to rainforest destruction in Indonesia.

Nestle’s top brass have made it clear they support GM food – and will back it to the hilt. In 2013, the Grocery Manufacturers’ Association in the US was forced to reveal the donors for its campaign against mandatory GMO labelling in Washington state. The three biggest donors were Pepsico, Nestle and Coca Cola. In 2012, the same companies, along with Kraft, had contributed millions of dollars to defeat a proposal that would have required the labelling of GM foods in California.

But elsewhere, it has had to give in on this issue. In 2012, a Brazilian court ordered Nestle to label anything containing more than one per cent genetically modified ingredients on its products sold in the country. The same year, the African Centre for Biosafety found that Nestle’s Cerelac Honey contained 77.65 per cent GM maize. The resultant outcry made Nestle announce in 2013 that its infant cereal in South Africa used non-GM maize.

Nestle has not been able to confirm that it does not buy cocoa produced by child slaves on cocoa farms in Africa, says Corporate Watch.

Apart from having been accused of breaking unions in its units in Columbia and Thailand, Nestle has also been accused, along with other coffee giants, of not having a fair trade policy that ensures its coffee-growers a living wage.

Its bottled water plants have faced a lot of opposition in at least three countries, including in our neighbour Pakistan. Nestle was indicted of abusing Brazil’s water resources for its `Pure Life’ bottled water in 2001. But it appealed against the court’s decision, and continues with its demineralization of Brazil’s groundwater as the appeal has not been decided.

In the US, it has faced opposition to using groundwater in Texas, Florida, California, Maine, Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, with court rulings against it in some of these states.

In the UK, in 1995-96, Nestle was found to have violated water pollution laws.

In 2008, Nestle was ordered to withdraw 200 tons of imported milk powder in Columbia because their labels carried false production dates and also the wrong country of origin.

Misdemeanours in India

While researching this information, I stumbled upon instances of the Indian authorities having cautioned Nestle more than once. As recently as 2012, the Ministry of Women and Child Development wrote to Nestle that it had been informed by the Indian Academy of Paediatrics that Nestle Nutrition Institute had organize seminars for paediatricians and other doctors across India.

The Ministry reminded Nestle of two letters it had written to it in 2010, informing the company that such activities violated the Infant Milk Substitutes Act. Yet, in January 2011, Nestle went ahead and violated this law again by signing confidential agreements with four universities which would enable it to hold nutrition awareness programmes for adolescent girls in government schools.

This information was contained in a blog post by Rema Nagarajan of the Times Insight Group, which ``has a mandate to look at stories beyond and behind the headlines.’’ Obviously, the print edition of the Times does not look at its own blogs, at least those that go beyond and behind the headlines!

Of course, not every journalist covering the food beat is expected to be aware of all this. But what about seniors on the beat, as well as those on the health/nutrition/environment beat?

Glowing praise of the Nestle brand

We had constant references to Indian consumers’ ``trust’’ in Nestle’s brand over the last 30 years, and articles tut-tutting Nestle’s inexplicably ineffectual handling of this PR disaster, along with tips on what it should have done. Is it the journalist’s job to tell a multinational how to handle a situation where it has been found wanting by the country’s premier food testing authority?

What took the cake was the reference to the ``glory’’ reached by Nestle. ``Hit by the lead and MSG content controversy and the subsequent consumer rejection, Maggi may lose out on its glory of being a Rs 2,000 crore brand this year, even as new brands which have been on the path of growth enter the elite club,’’ said a Times piece, going on to wonder, ``if the air surrounding product quality and labelling concerns are (sic) not cleared soon, the bigger issue remains as to whether the brand will bounce back to its past glory.’’ Indeed.

Then there were the opinion pieces such as Santosh Desai in the Times and Dhiraj Nayyar in the Hindu which, apart from harping on the ``trust’’ we all supposedly had in Nestle, cast doubt on India’s testing standards. Western testing standards were far superior, they said, implying that we should take the FSSAI’s findings with a pinch of salt.

Now there’s nothing wrong with criticising our own labs, but surely such criticism should be substantiated? Neither of these opinion writers did that. In a discussion anchored by Barkha Dutt, where three speakers were openly for Nestle against the sole representative of the lab which had first found the allegedly defective sample, Tavleen Singh went so far as to say that one could ``eat off Swiss toilets’’ (Nestle is a Swiss company) while we could neither trust our own labs nor the medicines handed out by our ``filthy’’ public hospitals.

Why would a renowned multinational go out of its way to flout standards, she asked? It was left to Shobhaa De, herself not a strong critic of Nestle on that show, to point out that multinationals didn’t think twice about lowering standards for India.

No lessons learnt from Bhopal?

Nobody pointed out that it was a major multinational that had been found guilty of ignoring safety standards in its Bhopal plant, leading to the world’s biggest industrial disaster and the death of 4000 in one night and many more since. After another big brand - Dow Chemicals - bought the plant, it refused to clean up the toxic waste left in it by Union Carbide.

Interestingly, at that time, most journalists had blamed Union Carbide alone for the disaster, not mentioning at all the responsibility of the Madhya Pradesh government of carrying our regular inspections of the factory. For these journalists, many of them considered ``progressive’’, the MP government, then headed by the media-savvy Arjun Singh and run by his trusted bureaucrats, rolled out the red carpet when they came to Bhopal to cover the disaster.

A few young reporters, however, insisted that the state government was equally, if not more at fault, and exposed how Arjun Singh had enjoyed Union Carbide’s hospitality in the past. These journalists had to run around getting information on their own and were left out of all government help while covering the incident. Today, the offending multinational is being treated with kid gloves by the press, and opinion writers are blaming the government. What can we conclude from this?

Irrelevant nostalgia that obscures the main point

On her show, Barkha Dutt did keep the questions coming, but effectively countered the arguments of Nestle’s defenders in her Hindustan Times column, in which she fleetingly mentioned Nestle’s baby milk controversy. Similarly, in the Hindustan Times again, Abhishek Saha’s love letter to Maggi mentioned in one sentence its baby food and bottled water controversies. The rest of it was nostalgia, as was a substantial part of Dutt’s column.

Indeed, every newspaper has carried at least one nostalgic piece on Maggi noodles. Apparently, everyone younger than this writer has grown up on it. One or two writers admitted they knew Maggi noodles had zero nutrition, but what the hell, those two-minute noodles were the saviour of all college hostelites.

Well, everyone knows those coloured ice candies my generation grew up on were really toxic if eaten regularly. Can I write a piece eulogizing them just because I used to eat them as often as I could? What about those who swear by Coca Cola? Can they write a paean to it without mentioning its deadly effects?

Perhaps I am over-reacting here but surely publishing recipes for Maggi noodles (`Five Maggi recipes that made our childhood special’ – the Indian Express), just after the product has been banned on health grounds and publishing a list of other noodle brands and how they are eaten (`The noodle world beyond Maggi’ - DNA), when suspicion has been cast on all instant noodles, is irresponsible journalism?

Apart from that, doesn’t the DNA piece amount to nothing but an advertisement for the instant noodle brands mentioned?

Then there were articles about mothers searching for alternative instant foods to pack for their children. Again, no mention was made about the damage such foods do.

What is the journalist’s role here? If it is not to play `health food advisor’, surely it is not to write as if it’s perfectly OK for one unhealthy snack to be substituted by another, thereby acting as a spokesperson for the instant food industry. It’s hard enough for nutritionists as it is to get the message across that such foods are unhealthy given the massive advertising by this industry.

Finally, the sheer scale of coverage of the Maggi Noodles episode was overwhelming. Without going into the old but still valid argument that many important issues do not get the space they deserve in the press, it can still be asked: did the discovery of excessive and harmful ingredients in a well-known ("trusted’’) brand, and the subsequent ban on that brand deserve that much coverage?

If there’s one thing that became crystal clear from the press coverage of the Maggi scandal, it was the grip that advertising has on the press.

Such articles are only possible because of your support. Help the Hoot. The Hoot is an independent initiative of the Media Foundation and requires funds for independent media monitoring. Please support us. Every rupee helps.