Honour all without favour

On September 4, 2014, two days before floods wreaked havoc in Kashmir, two TV reporters, Nazir Masoodi of NDTV and Aasif Suhaf of News24, waded through chest-deep water trying to reach the first floor of the Bone and Joint Hospital in Srinagar where patients had just been moved to the upper stories as the water level kept rising. It had been raining torrentially non-stop for days.

Moments later, both rushed to Bemina where the water had broken one of the dykes of the flood channel. With their wet clothes on, the duo continued reporting, making their way to house after house where hundreds were still trapped.

Scenes like these became common in the days to come. Journalists, most of whom had no information about their own relatives, continued covering the floods, putting their lives and the lives of their colleagues at risk.

With limited boats, no life jackets and no telecommunication network, dozens of Kashmir-based journalists preferred covering the catastrophe and saving trapped people rather than staying with their families in safety.

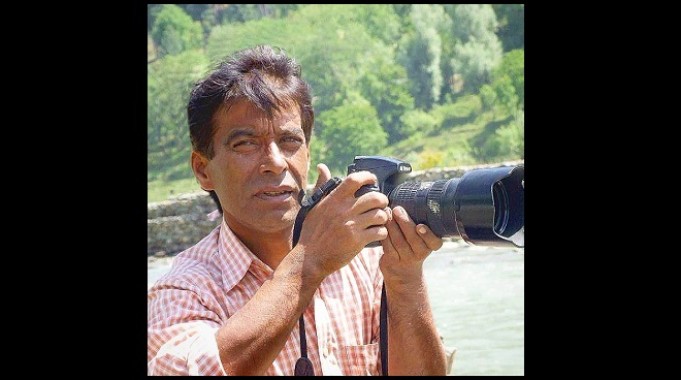

One of them, Shafat Siddiqui, who contributed his photographs to Pacific Press and Dainik Jagran, was found dead with cameras still slung around his neck on September 11, five days after he went missing. According to his family, Siddiqui was asked by his office to photograph the clock tower in Lal Chowk.

“He had no fuel in his car. They called him again and he went out to fetch petrol and then left at around 10.30 am,” The Indian Express quoted Siddiqui’s uncle as saying on September 24.

When reporters from Delhi landed to cover the floods, most of them were not clear how to access the areas submerged under water, who to contact and how. The administration, by the then Chief Minister Omar Abdullah’s own confession, was missing. The only working solution for covering stories was to either explore possibilities around Srinagar airport (which was untouched by the floods) or follow the army operations.

Many journalists who opted for the latter almost acted like embeds, prompting criticism that the army was using its rescue efforts as a public relations opportunity. Questions like: “Are you grateful to the army personnel who rescued you?” put by some reporters were controversial and the recreation of scenes was also not unethical.

The fury of locals against this phenomenon rose to such a level that the reporters, who had been working out of the Valley, had to remove the logos of the channels from microphones for weeks after the floods as they feared a backlash. Most of the journalists and editors in Delhi did not understand the sensitivities on the ground. Scenes like these were repeated in the aftermath of the Nepal earthquake.

Cut to November 23, 2015 and the Ramnath Goenka awards in the capital. Journalists like Siddiqui did not find even an honorary mention in a ceremony that attracted some of the biggest names in Indian politics and the arts. Though Siddiqui lost his life while on duty, a Delhi-based reporter won the award for reporting on the Kashmir floods.

This is not an aberration. Most journalists who work from small towns or the hinterlands share a similar fate. They break stories which high-profile journalists sell, face intimidation and live on meager salaries. Often labeled as ‘contributors’ and ‘stringers’, they have no contracts with the organizations they work for and do not win awards or fellowships. Paid per story or per picture, they are, as the Dainik Jagran editor in J&K, Abhimanyu Sharma, said when referring to Siddiqui, “stringer[s] who contributed pictures as ‘shouqia’ (as a hobby).”

(left) Tarun Kumar Acharya, (right) M.V.N. Shankar

Such cases exist all over India. Tarun Kumar Acharya, who worked as a stringer for Kanak TV, a local Oriya TV channel, and as a reporter for Sambad, one of the largest circulated Oriya newspaper, was found murdered on May 28, 2014. Acharya was allegedly killed over a news item on children working in a cashew processing unit. According to the police, the owner of the cashew plant arranged contract killers to eliminate Acharya.

Similarly, in November 2014, M.V.N. Shankar, a senior journalist for the Telugu-language daily Andhra Prabha, died at a local hospital a day after being beaten by assailants with iron rods. Shankar had frequently reported on the oil mafia.

None of them was deemed fit for something like a special category award called the Journalism of Courage which The Express Group declared for its correspondent Vijay Pratap Singh who died due to the injuries he sustained in a bomb blast in Allahabad on July 12, 2010.

And, this is not the case with only the Ramnath Goenka awards. It is true almost everywhere. Since these journalists are not staffers or do not work for big corporations, they are not even nominated for awards.

There is absolutely no doubt Singh deserved the award but so do the Siddiquis, Acharyas and Shankars of the world who report in adverse conditions, with limited resources and without much backing from the organizations they work for. The idea of the awards should be to honour brilliance wherever it can be found, even if it means seeking out those who may never be nominated.

Gowhar Farooq is an assistant professor at the AJK MCRC, Jamia Millia Islamia