How the Pakistan media fed Qandeel to the jackals

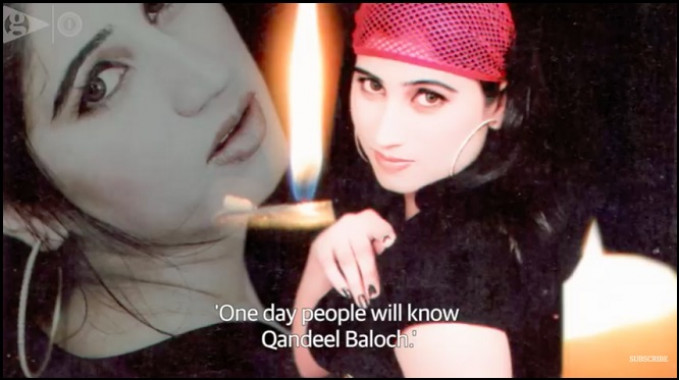

Qandeel, the Guardian and Bertha Foundation’s collaborative documentary, is a primer in under 25 minutes for those uninitiated about Qandeel Baloch, Pakistan’s mercurial actor, singer, and video blogger (or vlogger). Saad Khan and Tazeen Bari, both filmmakers credited with earlier films around the working class and women’s struggles, have directed it. The film is available on YouTube.

It comes more than a year after Baloch was allegedly killed by her brother on July 16, 2016, for rattling the power structures of her country with her sexually assertive conduct and inviting the unforgiving scrutiny of a morally bankrupt news media. In its brevity of sharply packed content lies the film’s soul, but the same leaves it suspended in mid-air for want of deeper context.

Qandeel can be seen as composed of three parts. One, the set-up of Baloch in her most popular avatar as social-media vlogger who meets us as a youthful woman sitting or lolling about her bed in short dresses and artful make-up, teasingly addressing her viewership of millions.

Second, the exposition in the dusty by-lanes of rural Punjab’s Shah Sadar Din town, part of Dera Ghazi Khan district near Balochistan. We are told a teenaged Baloch journeyed from here - watching television from a charpoy in her mud-floor room - to being on that television herself. Here Qandeel Baloch is singing on Geo TV’s show ‘Utho Jago Pakistan’.

When this chunk is followed by religious clerics or mullahs on prime-time debates preaching patriarchal interpretations of Islam while young men in public places mundanely chew on dinner, it links up as the gendered world Baloch had been wrestling.

In the film’s final segment, Baloch is in a clash with these state-sanctioned actors of patriarchal wisdom while the media, primarily television media, peddles toxic propaganda to bring in her violent end.

The media mess around Qandeel Baloch

The alternative media did a kind job, such as Bumbu Sauce’s song ‘Vuzzeerayazam’ (Grand Minister or Prime Minister), dedicated to Baloch for her outspokenness. But if what mainstream newspersons said about Baloch in the garb of news is called out as abetting the damning consequences that followed, it will not be an exaggeration.

One of the telling news clips in the film is news anchor Mubasher Lucman’s interview of Baloch after her Facebook page was blocked in March 2016. Lucman lectures a defiant Baloch that she could have to face legal consequences or fatwas for indecent behaviour.

Not long after that she was slapped with a legal notice for “bringing shame” to the Baloch race. Then followed some shaming by the media, an on-air face-off between Baloch and her ex-husband, the over-used mullah-(Mufti Abdul Qavi)-versus-model trope, and the devastatingly lowly action of publishing her identity documents and marital history. In naming and shaming her, the media stripped Baloch’s family of the insulation that she had cultivated through the pseudonym Qandeel Baloch.

Another pivotal piece of media spectacle is the press conference in which Waseem Azeem, Baloch’s younger brother and alleged murderer, confessed to killing her while giving his reasons. All media outlets scooped up his words as absolute truth, vilifying him as the sole villain (even when he was not the only accused and Qavi was also a person of interest in the case at that time).

The investigation had barely started but no one questioned whether such media interactions by the accused conformed with standard ethical operating procedures. Qandeel offers many such crucial clips of the berserk media without comment, just holding up the proverbial mirror.

The film, however, seems frozen in the time immediately succeeding Baloch’s murder and at her brother’s public confession to the crime. Even if it was a conscious decision, it makes the film dated. There have since been notable developments such as Baloch’s parents changing testimonies and the move to alter Pakistan’s honour killing law to deprive killers of the benefit of a pardon by paying blood money.

Striking stylistic treatment

In the aspects that Qandeel addresses, it is not distinct from other documentaries on Baloch that were released around the time of her death anniversary but its stylistic treatment makes it a film worth bookmarking.

There is a palpable emphasis on the film being driven by Baloch herself - through her vlogs, her audio recordings, her writings, and her TV interviews. The tight editing, the simulation of a Facebook ‘live’, the black screen overlay when audio is the critical document at hand, and splicing in a few of the telling pieces of TV debates involving Baloch, show a rigorously scripted film. Music is judiciously employed as a subtext, as in this audio-only social-media ‘live’ by Baloch.

In its narrative, Qandeel offers a fair recapitulation of Baloch’s story but a few things are not coherently tied up with necessary surround-sound. For example, three appearances of a montage of harassed vloggers stick out for lack of context about them. (A few of them are mujra dancers, popular entertainers for the working class in Pakistan who have been the subject of a film by director Saad Khan). Killing for ‘honour’ and the alarming statistics of Pakistani women consumed by it are a skipped detail.

The deaths that preceded hers

Moreover, another critical point left out is that Baloch is not the only woman from her class to have been physically attacked.

Back in 2007, entertainer Saima Khan (alias for Attia Khanum) was shot in her legs. A little before that, controversy had surrounded her when she took off her shirt during a live dance performance.

In 2014, the home of Honey Shehzadi, a mujra performer, was fired at, by unknown assailants. Her guard and a relative were killed.

A few months after Baloch was killed, mujra performer Kismat Baig was shot dead in Lahore after two previous attempts to murder her. There has been a long history of female entertainers in Pakistan being fatally attacked. The absence of protection for working class women is worth noting. This has claimed an alarming number of women performers in the previous decade including Ghazala Javed,Yasmin Gul, and recently on October 9, Shamim (aka Shamo).

By not juxtaposing Baloch with other women entertainers who were also considered sexually provocative, we do not see how her aspirations were distinct. She sought to gain a geographically vast viewership of smart-phone users through social media rather than be the star in nondescript theatres in Punjab. She spoke in English or in anglicised Urdu, mostly wore western clothing, and set up base in Karachi, a major urban centre - all signs of upward mobility in the subcontinent. This is a vlog of Baloch – on actor Fawad Khan, and men in the kitchen.

Consequently, such visibility made her a greater threat to middle-class morality and a compelling subject for the mainstream media.

As for Qavi, he had similarly confronted actor Veena Malik after a picture of her nude along with a visual making fun of the ISI appeared on an Indian magazine’s cover in 2011. Malik had shut him up with acidic responses.

But Baloch went beyond verbally countering Qavi. In her final months, she not only engaged with the clergy but with the other power lords of Pakistan - politicians and cricket players. The military was, perhaps, the only power centre that she spared. In doing this, Baloch was a politically conscious and not easily intimidated woman living all three waves of feminism at once.

For instance, Baloch’s Valentine’s Day video in a scarlet dress was a direct confrontation with Pakistan’s President Mamnoon Hussain who had called for barring the day’s celebration for its Western influence.

When she said “Go, Nawaz go,” she was calling for Pakistan’s then Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif, to be ousted, ahead of his rival Imran Khan’s rally in Lahore in May 2016.

Her most contentious step – promising an on-camera strip dance - is the only one of such moments to find a clear mention in the film.

Nonetheless, despite a few of these storytelling weaknesses, Qandeel is a notable film for its earnest attempt to capture the indefinable dent this 26-year-old made in her universe.

“If I die, there won’t be another Qandeel Baloch…for another 100 years’’, Baloch had said.