Who will protect the citizenry from the press?

When an ordinary citizen is defamed by a big newspaper, what recourse does he have?

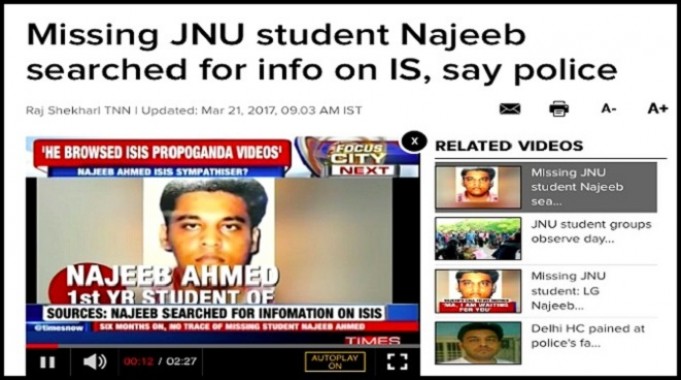

Something tragic and shameful happened this past week. The Times of India published a single column story on page one, on Najeeb, the long missing student at JNU, citing “police sources.” It said that his browsing history provided by Google and YouTube had now established that he was attracted to ISIS. A three-column story inside went into more detail: his Google searches related to how to join ISIS, and “highly placed sources” said that most of what he watched on YouTube related to the Islamic State as well.

The following morning the highly placed sources evaporated as the paper carried a single column page five announcement saying that the police denied the Najeeb report. And sourced it to the Delhi Police. Not as in a report based on a statement, but as in an advertisement. A statement, with authorship below given to the DCP, PRO, Delhi Police. Except that it was not an ad. And the paper carried no further story on the subject. Is this a new way of carrying a denial without owning responsibility?

Meanwhile Times Now had a story too, done by another reporter. The Financial Express did a strange double act, the day after the TOI’s scoop. The headline was about the denial, the intro and story lead were about the ISIS discovery, but again the last para carried the denial. Evidently the desk thought the ISIS story was too good not to be carried, even if the police had flatly denied it by then.

Sensational reporting has a ripple effect: every other media picked up the story.

After the damage had been done the alarmed family got a hearing—when they addressed a press conference at the Delhi Press Club. The Indian Express among others reported it the next morning.

Some WhatsApp has activism followed this with a petition being circulated, and the Delhi Union of Journalists issued a statement calling for the Times of India to apologise to Najib’s family on Page 1. JNU students protested angrily.

For the Hoot, the TOI story reinforces another tale of injustice carried the same week. An interview was filed from Kashmir by our contributor with one of the accused in the 2005 Delhi bomb blast case. He was released by a sessions court last month for lack of evidence. After he had spent eleven years in jail. He described how the Hindustan Times had reported that he was the bomber, based solely on police reports.

And had described him as a “hardcore” who has undergone the “toughest terrorist training and has been to Pakistan on a number of occasions”.

The difference between the two papers is only that HT got a chance 11 years later to make amends when it sent a reporter to speak to him and carried a story and video based on his version. But it was hardly enough to compensate a man who had been incarcerated for 11 years with the HT reports ensuring that he was assumed guilty by those who knew him and his family.

To return to the question we asked at the beginning, when an ordinary citizen is defamed by a big newspaper, what recourse does he have?

There is no peer condemnation. Fellow editors tend to mind their own business in these matters. They are happier holding the country's prime minister to account than a fellow editor who has not seen fit to make amends for a dangerously creative reporter.

Corporates resort to defamation notices whenever they are unhappy with media reporting. What does an ordinary Indian or his family do?

Will the Press Council take this up suo moto? It has chosen to become proactive lately in the matter of journalists' safety. But this is trickier, given that it has representatives of media on it. Will the owners and editors on it agree to censure the Times Group? Highly unlikely.

Journalists organize when they are under attack, or when they want to fight for their rights. They do not, sadly, choose to lose sleep over the harm done by their peers. So who will protect the citizenry from the press?