Between a rock and a hard place

In war, they say, truth is the first casualty. In a conflict zone like Kashmir, where there has been near daily conflict extended over more than two decades, the consequences include the obvious casualty of truth but many others too, multifarious and overlapping.

As the popular anti-India armed rebellion erupted in Kashmir in 1989, many journalists started becoming ‘soft’ targets for the armed forces, paramilitary personnel, policemen, government-sponsored counter-insurgents (renegades) and also the militants fighting for Kashmir’s ‘azadi.

Many journalists have been killed, intimidated, physically targeted, kidnapped, or coerced into toeing a particular line. They have been caught between the security forces and the militants, often sitting ducks for both. As the strife has mutated, journalists have faced different sets of problems in every phase.

The early stages of the conflict entailed threats of violence and kidnappings (which made journalists themselves the news). At other periods, journalists had to agonise about what to write - highlighting militants’ remarks made them guilty of ‘glorifying’ militants while carrying official statements branded them ‘government agents’. And currently, the biggest problem faced by the media is that newspapers are dying owing to the government deliberately not advertising in them, depriving them of income.

Along the way, another incremental casualty was the absence of women journalists. Conservative attitudes, the risks, and the combination of poor wages and working environments militated against women choosing it as a career.

In this article, I trace the major developments in the evolution of Kashmiri journalism, beginning with the most recent assault on a journalist.

From bullets and abductions to the more pleasant RTI woes

On the second Friday of Ramadan, 26 June, a group of young men mercilessly thrashed photojournalist Bilal Bahadur, who was covering the usual clashes between J&K police and stone-throwing youths in downtown Nowhatta, outside the Jama Masjid.

“I was taking pictures in Nowhatta Chowk. All of a sudden, a group of boys came nearer and attacked me without any reason,” says Bahadur.

Kashmir’s photojournalist association filed an FIR but later withdrew it as the attackers, allegedly sympathisers of a certain political party, came to the Press Colony to offer an unqualified apology for their misconduct.

Notwithstanding this incident, there have been some positive changes on the ground. “Compared to the nineties, journalists today have better tools to access information. The Right to Information Act (RTI) has broken the shell to some extent. Two, access to spot of conflict has also improved and journalists are allowed to meet victims. Earlier it wasn’t the case. That does not mean harassing and hampering journalists’ work is not there at all. There are still areas of work where restrictions are imposed directly and indirectly,” says Peerzada Ashiq, a journalist working for The Hindustan Times.

The RTI has been tremendously useful for human rights groups. It was used by the International Peoples’ Tribunal for Human Rights and Justice and the Association for Parents of Disappeared Persons – two prominent human rights bodies – to collate a 2012 report, “The Alleged Perpetrators”.

This revealed that 500 ‘alleged perpetrators’, including two Major Generals and three Brigadiers of the Indian army (besides many other serving officers and soldiers), were said to be involved in extra-judicial killings, torture, rape and other heinous crimes like abduction, extortion, and custodial disappearances.

However, Khurram Parvez, one of Kashmir’s leading human rights defenders and coordinator of the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, strikes a less enthusiastic note about the RTI.

“Getting information through RTIs is a long process in which officials frustrate the applicant if the information sought is sensitive. Generally journalists are in a hurry and therefore seldom invest time in these laborious processes. For sensitive matters like mass graves, fake encounters, disappearances, Village Defence Committees, Ikhwan (a pro-government militia comprised of surrendered militants) etc, officials invoke section 8 (1) (a) of the J&K RTI Act for withholding information,” Parvez argues.

Journalism is still a dangerous business

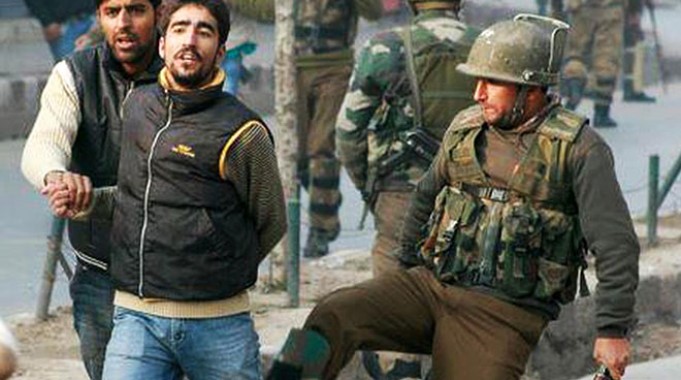

Photo by Qazi Irshad, Srinagar 2015

Mind you, any problems related to the RTI are a picnic compared to what journalists experienced in the early years of the militancy when they were caught between the ‘brutal’ state and equally brutal non-state actors.

Bashir Manzar was kidnapped by Ikhwan, the most feared government-sponsored counter-insurgent group.

Zafar Meraj, veteran journalist and editor of English daily Kashmir Monitor, and now a Peoples Democratic Party member, was once abducted by renegades, aka ‘Ikhwanis’.

On 7 September 1995, Yusuf Jameel, former BBC correspondent in Srinagar, who works for The Asian Age which is now owned by Hyderabad based Deccan Chronicle, survived a parcel bomb explosion in his Srinagar office after his colleague Mushtaq Ali opened the package addressed to Jameel.

Ali, who was working as photojournalist for AFP, was seriously wounded in parcel bomb blast and died a few days later. A symbolic memorial dedicated to him stands erected just at the entrance of Press Enclave, Srinagar.

“It was a letter bomb addressed to me. Fortunately, I survived. Unfortunately, Mushtaq Ali had to pay a heavy price for opening the parcel. After their threats, to shut me up, had failed the army tried to kill me through notorious renegade leader, Kukka Parray,” says Jameel Shah, who uses the nom de plume Yusuf Jameel.

He says it is not unusual to face intimidation. “In a conflict zone this is but natural. We have seen it in Karachi, Iraq, Afghanistan and many parts of the world. Violence has become part of our daily life. I, for one, decided to face it and take things in my stride,” he says.

Like other journalists, Jameel used to receive more than a dozen press statements from political parties and various militant outfits on a daily basis. And everyone expected full coverage of their statements on BBC radio in its then popular evening broadcast. If you didn’t, you were dubbed as pro-militant or pro-government. “It was a Catch-22 situation. A double-edged sword,” says Jameel.

The BBC advised him against taking any undue risks. “My organisation knew that I was being threatened by the army for quite some time. They advised precaution. I did take precaution and curtailed my movement, too. I wouldn’t go out alone. But who knew that perpetrators would target me with a letter bomb inside my office?” he says.

On 29 May 2002, unidentified assailants (suspected militants) shot at journalist Zaffar Iqbal, who then worked for Srinagar-based daily Kashmir Images and now for NDTV 24/7, from point blank range at the newspaper’s office in Srinagar.

Hapless Iqbal found himself lying in a pool of blood. No one believed he would survive multiple bullet injuries. Miraculously, he did.

“Journalists are sitting ducks. When perpetrators can’t beat the media persons, they get angry, and, in their frustration, find them as soft targets. Scribes working in a restive zone are expected to please everyone, but one can’t make everybody happy,’ says Iqbal.

Journalists in the early 1990s often found themselves making the news themselves, ‘thanks’ to being beaten, kidnapped or killed. In June 2006, some unidentified gunmen assaulted and attempted to shoot Shujaat Bukhari, former Special Correspondent of The Hindu who is presently editor-in-chief of Rising Kashmir.

A man accosted Bukhari near Lal Chowk in the evening, waved a pistol and directed him to get into a waiting three-wheeler vehicle, in which another man was already sitting. “At one point, one of the men received a call on his mobile phone. The auto-rickshaw abruptly changed direction. The vehicle stopped near Saidhpora, Eidgah, about 7 km from Lal Chowk, and I was pushed out and kicked. One of them then took aim at me and pulled the trigger, but the pistol failed to fire. Then they fled,” he recalls.

While the graph of violence in the last decade has fallen, it’s still difficult being a journalist in Kashmir. Riyaz Masroor, BBC’s correspondent in Srinagar, was beaten to the pulp by members of the Jammu and Kashmir Police outside his residence in July 2010 when a wave of pro-independence rallies rocked Kashmir.

This was during the summer agitation of 2010 when more than 120 persons, most of them teenage boys, were killed in police firing on various demonstrations. At the time, the Omar Abdullah-led coalition government in Jammu and Kashmir had announced that curfew passes were being issued to journalists.

“Kashmir had turned into a virtual prison because of severe restrictions in long curfews in 2010. People were living as prisoners. As soon as I stepped out from my house the policeman started beating me without giving me a fair chance to explain anything,” Masroor says.

He says that journalists working in Kashmir have learned the hard way and they now know how to survive through self-censorship.

“There is no need of coercion now, because conformity is so prevalent. If there is a Hindu-Muslim riot in far-off Kishtwar region, the English newspaper here will write that ‘goons from a particular community’ attacked, etc,” he says, adding that, “eye-witness accounts are not very fashionable here. The practice is such that we rely on the government for 90 per cent of the news flow.”

According to him, it will be very difficult down the line for anyone interested in history to figure out what journalists meant by ‘goons of a particular community’. Goons – which goons? A particular community – which particular community? “No one takes a position. Not even the opinion writers,” says Masroor.

Before putting pen to paper or speaking into a camera, he says, journalists have to think very hard. They know they face threats from people or groups whose interests could be hurt by what they say or write. Trapped between the two sides, most journalists usually weigh the pros and cons of a story very carefully, assessing and scrutinising it for every possible consequence.

Government advertising - the new weapon

Successive governments have curtailed the number of advertisements they give to some newspapers for their alleged “separatist content”. After the 2010 street protests, the Indian Home Ministry issued an advisory to cut back or place a blanket ban on government advertisements to the Jammu-based English daily Kashmir Times, the Srinagar-based Rising Kashmir and another English newspaper published from Srinagar.

“They just do it. They want newspaper editors to ‘behave’,” says a prominent journalist.

All government advertisements were stopped to Rising Kashmir between 2010 and 2012. The Kashmir Times continues to suffer heavily on the financial front because of the 2010 ban.

While everyone struggles with the effects of this lost income, reporters and sub-editors have to cope with another burden, that of editors telling them in subtly coded language what terminology and nomenclature to follow to avoid the risk of losing government advertisements.

That, says Manzar, is why newspaper terminology has changed over the years. “At the peak of the armed movement, the Urdu newspapers would first use the term ‘Mujahideen’ (holy warriors) for the militants. Then it kept changing from ‘Guerrilla’ to ‘Askariyat Pasand’ (gun-wielding rebels), to ‘Baagi’ (rebel), and finally to ‘Shidat Pasand’ (extremists/militants).’

Anuradha Bhasin, executive editor, Kashmir Times, says that the politics of controlling the media in Jammu & Kashmir started from 2010 onward. ‘The continued ban on our advertisement since 2010 has affected our circulation, quality and staff members,” she says.

Ms Bhasin points out that, in other Indian states, the media is corporate owned, but in Jammu & Kashmir, the army and intelligence agencies play the role of the corporation.

“There is no uniform or standard advertisement policy based on a newspaper’s credibility or circulation. The policy is whimsical. The government releases or stops advertisements to a newspaper based on whims,” she says.

The shifting media narrative

In the early 1990s, all leading newspapers from the Kashmir Valley would publish news and views reflecting the dominant public discourse, focusing on the Kashmir problem and human rights abuses at the hands of Indian armed forces, and coverage of the pro-azaadi movement and anti-India demonstrations.

“In the initial years of the anti-India armed rebellion, the front page, edit page, and op-ed pages of newspapers would reflect the dominant political opinion of Kashmir. The focus was on enforced custodial disappearances, human rights excesses by the army and paramilitary and even the opinion pages would talk about the resolution of the Kashmir issue, but that has significantly changed since,” says well-known journalist Naseer A. Ganai.

At one point, some top commanders of militant outfits like Hizb-ul-Mujahideen and the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front would write weekly columns in Srinagar-based Urdu newspapers, especially in the popular weekly ‘Chattan’. Some wrote under their real names, others used pseudonyms.

Muhammad Farooq Rehmani, chairman of the Jammu and Kashmir Peoples’ League, and Amanullah Khan, founder of the pro-independence Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front used to write columns for ‘Chattan’. Rehmani propounded his pro-Pakistan ideology while Khan argued for Kashmiri freedom.

“Their columns would generate a lot of debate in the early 1990s,’ says Bashir Manzar, former ‘publicity chief’ of the militant organisation, Muslim Janbaz Force and presently editor of the English daily, Kashmir Images.

Manzar himself used to write for ‘Chattan’ under the nom de plume of Vikas Gul. “Those were difficult years for journalists. There were no English newspapers then. ‘Chattan’ was the most popular Urdu weekly. Those days, it was the militant’s ‘darling’ newspaper. And believe me, ‘Chattan’ used to sell like hotcakes,” he recalls.

As the militancy weakened and the state government and security apparatus got a grip on the law and order situation in early 2000, newspaper coverage in Kashmir began to show a commensurate and visible change.

“Now you see the focus has shifted from Kashmir’s political dispute and its resolution to local issues of corruption and governance,’ says Ganai.

Regular front page stories about custodial disappearances, torture and extra-judicial killings started shifting to the inside pages. Many columnists who used to write about ‘resistance’ began writing about less controversial issues.

‘The difficult years have taught journalists how to survive. Now they know where the line ends. Today there is no threat from the militants, but there is self-imposed censorship because the newspaper finances are solely dependent on government advertisements,” says Manzar.

Journalism, they say, is literature in hurry. Journalists act as watchdogs of society and act as conduits between people and government. But sometimes the devil lies in the message and the messenger becomes the victim. Journalists in Kashmir have been through the wars, literally and figuratively. While the conflict may have abated, there are still landmines around which they have to watch out for.